By series 10 of the revived Doctor Who (series 36ish if you count from 1963), we find the Doctor’s twelfth(ish) incarnation hiding away in an earth university, where the Doctor gives lectures. ‘Totally awesome’ lectures according to Bill Potts, who works in the canteen and sneaks in just to hear them.

And all of this seems fairly natural because viewers believe that’s what the great Lord of Time does, right? He gives speeches. Wonderful, inspiring speeches that change people for the better. Or fearsome, ominous speeches that strike fear into the hearts of even the most powerful beings in the galaxy.

Well, not really. For the first 26(ish) years of the programme, the renegade Time Lord gave very few grand pronouncements where he expected people to listen. Many Doctors came and went – such as the second(ish), third(ish), and fifth – without making anything that could be described as a speech at all.

So, what do I mean by a ‘speech’? Let’s set out some criteria. A speech should be more than just an extra-long part of a conversation. It shouldn’t be a bit of exposition, where a character gives an info-dump of the plot or offers a solution to a problem. Nor should it be a (fourth-wall-busting) narrative voice, a character talking to the audience – bringing them up to speed, introducing a new location or direction (think the intros to The Deadly Assassin and the 1996 TV Movie).

What it should be is a soliloquy, a character speaking his/her thoughts aloud when alone, regardless of any hearers. Or a pronouncement towards a group of people that is meant to set out the speakers’ position and offer the listeners an insight or the chance to change as a result.

Back in the 405-line mists of time, the very first Doctor did have an occasional propensity to speechify. Although he claims not to offer people his counsel: ‘You wanted advice, you said. I never give it. Never,’ says the Doctor in The Daleks’ final episode, The Rescue. But this is itself a rhetorical device, as immediately after he says, ‘But I might just say this to you: always search for truth. My truth is in the stars and yours is here…’

After this, the first real speech the Doctor gives is not to impart wisdom and advice, nor is it to call out an enemy or cry for injustice. It is simply an outpouring of wonder at the universe…

‘I know. I know. I said it would take the force of a total solar system to attract the power away from my ship. We’re at the very beginning, the new start of a solar system. Outside, the atoms are rushing towards each other. Fusing, coagulating, until minute little collections of matter are created. And so the process goes on, and on until dust is formed. Dust then becomes solid entity. A new birth… of a sun and its planets!’

The First Doctor, The Brink of Disaster.

Not a hint of a ‘Billy fluff’ is audible in this commanding performance by Hartnell. And as is often with speeches, while it does little to move the plot on – there’s no revelation about a character or event – it tells you a great deal about the speaker. Here is a wide-eyed traveller, still in awe of the universe, despite his great age and experience.

Of course, it also serves the production well, as it saves the cash-strapped serial from having to use special effects to convince the viewers of the magnitude of the threat outside the ship. These powerful words, combined with Hartnell’s impassioned delivery, conjure up more than the 1960s BBC special effects department ever could.

But, much later, in The Massacre of St Bartholomew’s Eve, the First Doctor gives us a rare example of a soliloquy, where the audience are treated to an insight into the mind and motivation of the character without anyone in earshot. But first he addresses his companion, Steven Taylor, who is shocked that the Doctor doesn’t act to stop the carnage…

‘My dear Steven, history sometimes gives us a terrible shock, and that is because we don’t quite fully understand. Why should we? After all, we’re too small to realise its final pattern. Therefore don’t try and judge it from where you stand. I was right to do as I did. Yes, that I firmly believe. Steven…’ [Steven leaves; the Doctor is alone] ‘Even after all this time, he cannot understand. I dare not change the course of history. Well, at least I taught him to take some precautions; he did remember to look at the scanner before he opened the doors. And now, they’re all gone. All gone. None of them could understand. Not even my little Susan. Or Vicki. And as for Barbara and Chatterton — Chesterton — they were all too impatient to get back to their own time. And now, Steven. Perhaps I should go home. Back to my own planet. But I can’t… I can’t…’

The First Doctor, The Massacre of St Bartholomew’s Eve.

Okay, so it’s not a huge insight into the motivation of a near-immortal wanderer in the fourth dimension. But it does tell us that the Doctor is just as mindful of the people near and dear to him as the great cosmic and historical events he encounters. And this tension between the personal, emotional experience of time and the vast interwoven causal nexus of history is a theme that will continue throughout the series. Think Demons of the Punjab as the most recent example.

Besides this, there are few other examples of the First Doctor delivering a speech, rather than speaking a long piece of dialogue. The most obvious is the memorable address to Susan at the end of The Dalek Invasion of Earth:

‘Not any longer, Susan. You are still my grandchild and always will be. But now, you’re a woman too. I want you to belong somewhere, to have roots of your own. With David, you will be able to find those roots and live normally like any woman should do. Believe me, my dear, your future lies with David and not with a silly old buffer like me. One day, I shall come back. Yes, I shall come back. Until then, there must be no regrets, no tears, no anxieties. Just go forward in all your beliefs and prove to me that I am not mistaken in mine. Goodbye, Susan. Goodbye, my dear.’

The First Doctor, The Dalek Invasion of Earth.

It’s a tender and humble speech (‘silly old buffer like me’), where although the Doctor takes a decisive action in locking Susan out, he does it for the best of motivations. The meaning is slightly skewed, however, when it is used as a prelude to The Five Doctors. Out of context, it makes it seem like the Doctor is prophesying his reappearance in a future adventure, rather than – what it is – an expression of his desire to see his granddaughter again. And, remember, the Doctor at this point seemed to have little control of his time ship, making the hope even less certain, and the sacrifice greater.

When Patrick Troughton took over the role and the Second Doctor appeared, so the speeches disappeared. Troughton’s Doctor was not one for great pronouncements. He wasn’t a leader, prepared to rally the troops into battle. In fact, he mostly worked behind the scenes, maneuvering situations, and investigating causes to bring events to a conclusion through a series of subtle actions. The Second Doctor was often dismissed as a fool or an irrelevance. The way that his enemies underestimated his powers was the Doctor’s great strength.

This becomes an important observation as we will later find the Doctor making great claims about his abilities and how dangerous he is in order to defeat his enemies. His cry (from the Ninth Doctor beyond) is often ‘I’ve defeated loads of enemies countless times – do you want to chance it?. That’s usually coupled with the pronouncement that he ‘has no plan’, and that makes him all the more powerful. The Second Doctor takes quite the opposite approach: encouraging his enemies to ignore him while he, unobserved, enacts his intricate plans to defeat them.

There are two instances where the Second Doctor gives speeches. While the first is mostly just an extension of a conversation, it does give an insight into the Doctor’s inner life. In The Tomb of the Cybermen, he comforts Victoria Waterfield, who is still mourning the loss of her parents. When she asks if he can still see the faces of his absent family, the Doctor says:

‘Oh yes, I can when I want to. And that’s the point, really. I have to really want to, to bring them back in front of my eyes. The rest of the time they… they sleep in my mind and I forget. And so will you. Oh yes, you will. You’ll find there’s so much else to think about. To remember. Our lives are different to anybody else’s. That’s the exciting thing! There’s nobody in the universe can do what we’re doing. You must get some sleep and let this poor old man stay awake.’

The Second Doctor, The Tomb of the Cybermen.

Again, we see a pattern emerging of what preoccupies the Doctor. He does love and care for people close to him but he’s living for the moment (partly because he can’t go home). The universe is such an enthralling place to experience that it overcomes any sense of loss or grief. This goes back to the heart of the Doctor’s story (at this point, anyway). He ran away from home – leaving friends and family behind – because the universe was too tempting to ignore.

Fighting monsters and righting wrongs is just a sideline; he’s here for the adventure. Which also means accepting death and loss on the way, rather than trying to ensure all the good guys win and the bad guys are destroyed.

Once again, the Doctor is keen to dismiss his physical and mental prowess. Just as the First Doctor describes himself as a ‘silly old duffer’, so the Second calls himself a ‘poor old man’.

This strongly contrasts with the later revived Doctor, who is fond of stressing his/her own powers and the inevitability of defeat for all those who oppose him.

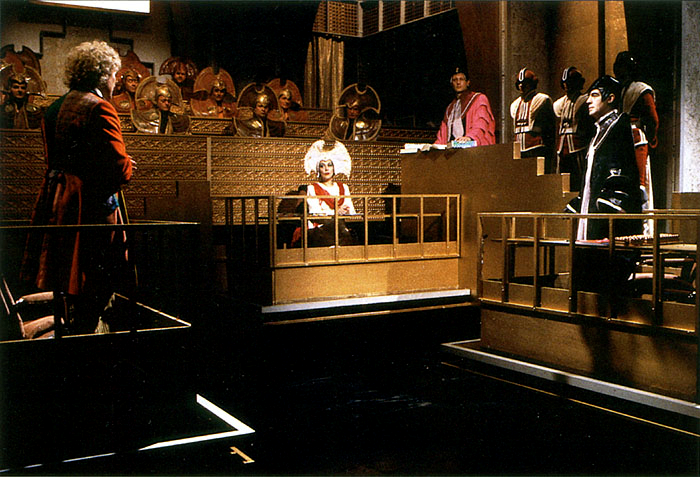

The only time the Second Doctor really makes a speech is when it is forced upon him. At the climax of The War Games, the Doctor has to reveal his location to the never aforementioned Time Lords. When they put him on trial for interference in the affairs of other planets, the Doctor is obliged to say a few words in his defense.

The Doctor: ‘The Quarks, deadly robot servants of the cruel Dominators; they tried to enslave a peace loving race. Then there were the Yeti, more robot killers, instruments of an alien intelligence trying to take over the planet Earth.’

Time Lord: ‘All this is entirely irrelevant.’

The Doctor: ‘You asked me to justify my actions – I am doing so. Let me show you the Ice Warriors, cruel Martian invaders; they tried to conquer the Earth too. So did the Cybermen, half creature, half machine. But worst of all were the Daleks, a pitiless race of conquerors exterminating all who came up against them. All these evils I have fought while you have done nothing but observe. True, I am guilty of interference, just as you are guilty of failing to use your great powers to help those in need!’

The War Games.

Although a lengthy speech (in Doctor Who terms at that time), it reveals little about the inner life or motivation of the Doctor. It’s rather a catalogue of nasties and their evil plans that the Doctor fought against. Sure, we’ve moved on from the early First Doctor’s wish to get back to the ship at the first sign of trouble. But even he declares to Ian that he wants to ‘pit our wits against [the Daleks] and defeat them,’ in The Dalek Invasion of Earth. But there’s no bravado directed at the enemies. It’s a stated intent shared with allies, a call to others to join the fight. It is the Time Lord’s ‘great powers’ that could help more people in need, and the combined wits of the Doctor, Ian, and others that will thwart the Dalek invasion.

When his appearance is change and Third Doctor arrives, little changes in terms of the volume of speeches. He is an authoritative Doctor, but most of his wisdom he emparts individually, usually to his companion.

In fact, arguably the longest section of dialogue in Who history (give or take a few interjections from Jo) is delivered by Pertwee. And it happens in The Time Monster, Episode 6. The single longest uninterrupted speech in the whole of Doctor Who on television is from the Eleventh Doctor. And it may not be the one you are expecting. That speech is 201-words long. If you take away Jo’s dialogue (which we’re doing; sorry Ms Grant), the Third Doctor’s ‘Daisiest Daisy’ story is a whopping 293-words long…

‘When I was a little boy, we used to live in a house that was perched halfway up the top of a mountain. Behind our house, there sat under a tree an old man. A hermit, a monk. He’d lived under this tree for half his lifetime, so they said, and had learned the secret of life. So, when my black day came, I went and asked him to help me… I’ll never forget what it was like up there. All bleak and cold, it was; a few bare rocks with some weeds sprouting from them and some pathetic little patches of sludgy snow. It was just grey. Grey, grey, grey. The tree the old man sat under was ancient and twisted, the old man himself – he was as brittle and as dry as a leaf in autumn… Nothing. Not a word. He just sat there, silently, expressionless, and he listened while I poured out my troubles. I was too unhappy even for tears, I remember. When I’d finished, he lifted a skeletal hand and he pointed. Do you know what he pointed at? A flower. One of those little weeds. Just like a daisy it was. I looked at it for a moment and suddenly I saw it through his eyes. It was simply glowing with life like a perfectly cut jewel, and the colours were deeper and richer than you could possibly imagine. It was the daisiest daisy I’d ever seen. Yes, I laughed too when I first heard it. Later, I got up and ran down the mountain and I found that the rocks weren’t grey at all. They were red and brown, purple and gold. And those pathetic little patches of sludgy snow were shining white in the sunlight!’

The Third Doctor, The Time Monster.

But is it a speech? I think it’s more of a story – an anecdote. It has a clear moral and it does tell us more about the Doctor’s past, much more than we will ever learn again about his childhood until the Tenth Doctor onwards. But, whatever the category, it wasn’t a story about how powerful the Doctor is. It was about his weakness, his doubt. And how, with the help of others, he can see things differently.

The Third Doctor’s only real speech comes at the end of Planet of the Daleks. Continuing the pattern, it is not a triumphant declaration before battle (‘Once more unto the cooling chamber, dear Thals, once more…’) but an afterword and a eulogy (I’ve taken out the interjections by Taron):

‘Yes, that’s what I mean. When you get back to Skaro, you’ll all be national heroes. Everybody’ll want to hear about your adventures… So be careful how you tell that story, will you? Don’t glamourise it. Don’t make war sound like an exciting and thrilling game… Tell them about the members of your mission that will not be returning. Like Maro, Vaber, and Marat. Tell them about the fear. Otherwise, your people might relish the idea of war. We don’t want that.’

The Third Doctor, Planet of the Daleks.

For me, this feels like a huge contrast to the revived Doctor’s attitude to his conquests. The ‘look me up’ confrontation with the Vashta Nerada or with the Atraxi at the end of The Eleventh Hour: ‘Hello. I’m the Doctor. Basically, run.’ It may not quite be making war sound like ‘an exciting thrilling game’ but it does appear that the Doctor is revelling in his triumphs. But we must also remember that, after the Time War, the Doctor is a very changed person. And also that these acts of bravado are used to prevent more bloodshed. And it works.

When the Fourth Doctor arrives, there is an attempt (at least early in his tenure) to give the Time Lord more speeches. The first is the celebrated ‘indomitable’ soliloquy:

‘Homo sapiens. What an inventive, invincible species. It’s only a few million years since they crawled up out of the mud and learned to walk. Puny, defenceless bipeds. They’ve survived flood, famine and plague. They’ve survived cosmic wars and holocausts. And now, here they are, out among the stars, waiting to begin a new life. Ready to outsit eternity. They’re indomitable. Indomitable.’

The Fourth Doctor, The Ark in Space.

And it is a pure soliloquy in the sense of a character revealing their thoughts aloud. While directed at the sleeping bodies of the humans in cryogenic suspension, there is no suggestion that anyone can hear the speech. Like the First Doctor’s description of the birth of a solar system, it’s an almost uncontrollable outburst when faced with a wonder of the universe.

While it does little to further the plot (in fact, it was cut completely in the 70-minute repeat version), it does much to add to the atmosphere, and the Doctor’s amazement at human survival tells us a great deal about his fondness for the species. As Philip Hinchcliffe has pointed out, the speech was partly to draw on Tom Baker’s strengths as an actor, as you couldn’t have given a speech like that to Pertwee. Or Troughton for that matter, but maybe Harnell would have revelled in the opportunity….

While a successful experiment, speeches of this kind do not become a hallmark of the Fourth Doctor’s era. You get the feeling that it was intended to be a character trait, as, in the same serial, when the Doctor ponders out loud about the life cycle of the Wirrn, Sarah explains: ‘He talks to himself sometimes because he’s the only one who understands what he’s talking about.’

But, although the Fourth Doctor tends to talk above people’s heads for the rest of his tenure, this tendency to talk out loud to himself happens very rarely. Actually, the Fourth Doctor doesn’t really make any more speeches. He tends to babble a lot more (amusingly) in Douglas Adams’s scripts and rewrites, but nothing like the ‘indomitable’ interlude.

The Fifth Doctor delivers no speeches at all. I can’t find any. And it’s usually because, like the Second Doctor, he acts behind the scenes and – despite physically having a more commanding presence than Troughton – he is not always treated as a great authority figure by those around him, not even his companions.

The clearest example of this is Director Ambril’s dismissal of the Doctor’s warnings in Snakedance: ‘Have him thrown out… The man’s clearly deranged.’ People not heeding the Doctor’s warnings which results in disaster is a recurring theme throughout the classic era, again often in contrast with the revived era where he more easily takes control. That’s why it’s such a shock in Midnight when the Tenth Doctor’s authority is questioned and the passengers gang up to throw him off the shuttle.

The closest the Fifth Doctor gets to a speech is in Earthshock, when he challenges the Cyber Leader’s dismissal of emotions:

‘Emotions have their uses… They also enhance life. When did you last have the pleasure of smelling a flower, watching a sunset, eating a well-prepared meal?… For some people, small, beautiful events is what life is all about!’

The Fifth Doctor, Earthshock.

But it’s hardly a speech; more an outburst as you can’t imagine the Cyber Leader’s mind changing as a result of the Doctor’s interjection.

With the arrival of Colin Baker as the Sixth Doctor, once again the part is taken by an actor to whom speechifying seems to come naturally. In fact, in his first outing, The Twin Dilemma, despite the Doctor’s mind being in turmoil following his regeneration, he delivers five lengthy sections of dialogue. That’s five times more that the whole of the Fifth Doctor’s era. But mostly these are, rather unfortunately, intended to reveal what an arrogant, pompous twit the new incarnation of the Doctor is:

‘I am a living peril to the universe. If this poor hive is to be cleansed, there’s only one recourse. Contemplation. Self-abnegation in some hellish wilderness. Ten days, ten years, a thousand years! Of what consequence is time to me? I shall become a hermit, and you, child, shall be my disciple. I know the very place. An asteroid so desolate. Titan Three is where I shall repent!’

The Sixth Doctor, The Twin Dilemma.

Presumably, like the Fourth Doctor’s early speech, these were intended to continue throughout the Sixth Doctor’s era. But they don’t. And, while the Doctor wavers between arrogant and charming, the pompous speeches are (thankfully) dropped.

The most important speech of the Sixth Doctor’s era comes very near the end (and from the pen of Robert Holmes, who also wrote the ‘indomitable’ soliloquy). When the Doctor discovers the Time Lord’s corruption that has led to near-destruction of planet earth, he says:

‘In all my travelling throughout the universe, I have battled against evil, against power-mad conspirators. I should have stayed here. The oldest civilisation: decadent, degenerate, and rotten to the core. Power-mad conspirators, Daleks, Sontarans, Cybermen – they’re still in the nursery compared to us. Ten million years of absolute power. That’s what it takes to be really corrupt.’

The Sixth Doctor, Trial of a Time Lord.

This is a rather neat reversal of the Second Doctor’s speech at his first trial, the Sixth Doctor discovering that it’s not the Time Lords’ inaction that is an outrage – it’s the way they use their great power for self-interest that is the real crime. It’s a powerful speech, delivered passionately by Baker. And a sad indication at how misused the actor’s commanding authority was in his televisual outings. (Fortunately, Big Finish, while staying true to the character, have done much to rectify this…)

The Seventh Doctor delivers a few important speeches, but the most revealing are in Remembrance of the Daleks. And I think this is the most significant, delivered to the Emperor of the Daleks (later revealed to be Davros):

‘Ah, there you are. This is the Doctor, President Elect of the High Council of Time Lords, Keeper of the legacy of Rassilon, Defender of the Laws of Time, Protector of Gallifrey. I call upon you to surrender the Hand of Omega and return to your customary time and place.’

The Seventh Doctor, Remembrance of the Daleks.

It’s the first ‘authority’ speech given by the Doctor, where he declares his supremacy and calls upon his enemy to surrender. It comes out of Andrew Cartmel’s positioning of the character as an arch manipulator, a powerful being with a battle plan.

And in many ways this re-frames the character forever, particularly in the revived era. Which I will (along with the TV Movie) discuss in part two of this exhaustive (don’t say exhausting) article…