Alex Skerratt recently asked whether there is room in Doctor Who for religion, Christianity in particular, and whether we might see a companion with overt faith. As he rightly notes, the original series rarely addressed religion and was never contentious. When it did, there was always a distance, be it temporal or conceptual, such as with The Aztecs (1964) or Kinda (1982). But with the national religion, the BBC was cautious of giving offence and, even in the celebrated The Daemons (1971), the church crypt became the ‘cavern’ for fear of raising controversy. And classic companions often entered the TARDIS as if newly born; with their families and backgrounds — let alone their values and beliefs — scarcely mentioned.

Our new century is quite different. In the UK, belief in the supernatural, religious affiliation, and church attendance are all in long term decline, especially among the under 50s. The stigma that once attached to atheism is gone, and the beliefs people do hold are more inchoate and less regimented by doctrine. Indeed, one 2015 UK poll found that belief in a god ran at only 55% among those who identified as Christian. With this loosening of religion’s bonds (St. Augustine derived the word partly from the Latin ligare, meaning to bind, as with ligature), there has been space and time to address organised faith in NuWho, if only in passing. I think bringing a companion with a strong religious conviction for a spin in the TARDIS could — if handled intelligently — make for a fascinating set of stories. However, I’d caution Alex and others to be careful what they wish for: how well would faith survive the experience? It’s that which I will explore here, using Christianity as my case study only because I know it best.

Let’s imagine, then, that the writers decide to explore faith by giving our Doctor a religious companion. They could have her meet a fundamentalist Christian from the American deep south but, for all the fireworks that might follow from the Doctor showing her new charge conclusively that the earth is neither flat nor 6000 years old, I think the writers might reasonably be accused of shooting ichthyses in a barrel. Instead, let’s be realistic and assume they would create a 21st Century British, church-going Christian woman. I shall call her Eve. Given her era and science’s inexorable colonisation of once hallowed ground, Eve would likely already accept as uncontroversial the age of the earth, a heliocentric solar system, and – as much as any of us can – the vastness of the universe. But how would exploring even a sliver of ‘those millions of planets, eons of time’ and ‘countless civilisations’ affect her relationship with her god?

Series 13 story arc?

A tour of earth’s history alone ought to be enough for Eve to begin putting her own faith in perspective. We know of around 4,300 religions and about 3,000 gods during the past 12,000 years alone, and many more are likely lost to us. A realistic depiction of a religious companion would need to consider their response to that cacophony of competing hosannas. If only in a montage, we could be shown Eve listening patiently as the votaries of countless faiths each told her authoritatively how the world had come to be, how it would end, how people should live, and why their faith was the one true religion and theirs the only god(s). Eve would soon come to see the many borrowings and resemblances between religions, hearing frequently of miraculous births, of great floods, of saviours, and of dying-and-rising gods. Exposed to this diversity, Eve – if realistically written — would also find it hard not to realise that the primary determiner of faith is not revelation, reflection, or persuasion but location. We generally inherit faith from our culture. The woman growing up in 1960s America would almost certainly be a Christian, while the man living in Mesopotamia around 3,500BC would likely worship the god associated with his city, perhaps Inanna. Despite the 5,500 year gulf between them, Eve would find both equally convicted of their faith, although the Uruk man would cheerfully acknowledge that his was just one of several gods.

Importantly, Eve and the Doctor would meet many good people, each elevated by their faith to great compassion, achievement, and sacrifice. They would see beautiful buildings, luminous art, inspiring literature, and soaring music made as acts of devotion. They would also see the same religious certainties drive or justify great acts of cruelty and brutality. The unbelievers, too – the atheists and the agnostics – would pen haunting verse, comfort the sick, and brutalise the weak. In other words, the same picture we see today but painted across millennia. Could our future writers, contemplating such experiences as these for Eve, have her avoid reaching two conclusions in particular: that religion alone makes us neither good nor evil, and that none has profoundly altered the human animal?

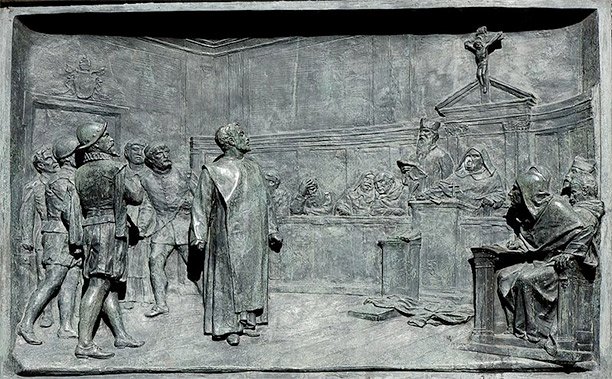

Travelling with the Doctor would present many opportunities to test Eve’s confidence in her faith and the authority of its church. Standing in Fatima in October 1917, might the Doctor breezily lecture Eve on meteorology and crowd psychology as thousands of believers claim to have seen the sun ‘dance in the sky’? Might the pair then hop forward to 1940, to hear Pope Pius XII declare the ‘miracle of the sun’ official? Perhaps the Doctor could take Eve to Salem in 1692, when Exodus 22:18 was not merely a source of polite embarrassment but a mandate for murder. Maybe the writers could explore Eve’s reaction as, holding hands with the living proof, she stands in a Rome market square in February 1600 while Giordano Bruno, naked and gagged, burns alive to the sound of a choir for his conviction that there is life on other worlds. Could we watch Eve attempt to reconcile her belief in the eternal fire of Matthew 25:41 after visiting any of the estimated 47 billion people who lived and died before 1AD? How would Eve console a grieving Catholic mother, tormented that her miscarried baby was denied heaven and instead consigned to eternal limbo? In the TARDIS later, might the Doctor comfort Eve by telling her that, by 2007, the Church would at least concede that there are ‘reasons for prayerful hope’ if not ‘grounds for sure knowledge’ that this fabricated obscenity might not be real?

The better Doctor Who historicals have always managed to reconstruct vital, living people from dry, dusty textbooks. It seems inescapable to me that a Christian companion would ask to witness the life of Christ. How would the writers tell the story of the real people? Any authentic telling would have to immediately dispense with the fiction of the Nativity, which was an invention to satisfy the theological need for the messiah to be born in the ‘City of David’. We know Luke’s account (written 70 years later) of an Augustan census that – uniquely in all recorded history — required everyone to return to the city of their birth is unsupported, is incompatible with established history, and conflicts with the mountain of evidence demonstrating the Romans to have been superb (not to mention sane) administrators. A story set in those times could honestly depict a charismatic, eccentric rabbi named Yeshua, but only his baptism by Yohanan (John) and his crucifixion on the instruction of Pontius Pilate are considered historically reliable (even if the Gospels cannot agree Yeshua’s last words). For dramatic purposes at least, a writer might choose to accept the ‘Gospel truth’ as sufficient to depict the resurrection, but surely then there is a much better tale to be had from Matthew (27:51-53) – and a ‘base under siege’ story at that:

The Doctor and Eve’s first Easter break doesn’t go to plan as an army of corpses is raised from the dead and invades the streets of Jerusalem. That’s ‘Tombs of the Holy People,’ this Sunday at 6.45pm.

Our future showrunner could easily fill a run of episodes in which Eve asks the Doctor to see the birth of Christianity, itself. Hopping over the Middle East in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, they would have found competing factions of the new religion warring over what were to be Christianity’s core precepts. Eve could meet the Christians who, like her, believed in the one deity, but she would also meet those who would argue as passionately that there was the evil god of the Old Testament and the loving god of the New. Indeed, it was these Marcionites who first divided the Bible into Old and New Testaments, precisely to demonstrate what they saw as the fundamental incompatibility between the loving Jesus and the genocidally sadistic Hebrew monster who drowned men, women, children, and animals over a tortuous 40 days and nights. Eve might also meet Gnostic Christians who would speak of 12 gods, while others – still Christians – would number it at 30 or 365. She and the Doctor might sit in meetings debating whether Jesus was all human, part divine or fully a god. And the writers of these episodes would have to depict all these people as adamant they were following the teachings of Jesus and had scripture to back them up (sometimes amending it to further a particular cause).

What effect would it have on Eve, were she to witness the debate, dispute, and even violence that persisted for decades until, on each point of contention, one or other side won out, the doctrine of Christianity was hammered into place, and the canonical Bible assembled? How much comfort would Eve draw, for instance, in seeing the Infancy Gospel of St Thomas excised from the canon so that Jesus had not – officially — murdered a child for throwing a stone at him? Would she not wonder why a book believed to be divine contained not a single new thought or standard, not one single radiantly anachronistic insight to demonstrate its supernatural origin? I find it hard to believe that a realistically written Eve, having seen all this, would not see her own belief as newly precarious; one inheritance among a multitude, its previously ‘divine’ truths the product of very human squabbling. In fact, how much fun might the writers have if they chose to have the Doctor rewrite the Bible to make it beneficial and miraculous: perhaps a chapter on the germ theory of disease, accurate astronomy, and a head start on Darwin? Gone, for instance, the guidance on the ‘proper’ way of looking after one’s slaves and, instead, a ringing defence of the rights of women, and a celebration of racial and sexual diversity. Oh, and never eat pears.

And if the Doctor spared Eve a trip into earth’s future and took her out into the universe instead? Let our writers assume that all sentient species feel the same desire for understanding the world around them, the same yearning for answers, purpose, and meaning, and a shared longing to experience the numinous: that sense that there is something greater and higher than all of us. Extrapolate all that Eve has seen on Earth to billions of planets, perhaps each with its own history of competing, often warring, religions. How many gods would Eve hear of and how many religions would she encounter? How would that affect the strength of the faith conferred on her by her place of birth? How would Eve reconcile her belief in salvation only through acceptance of Jesus Christ, for instance, when meeting a species who lived and died a billion years before the Earth had even formed?

Of course, Eve would also find questions and mysteries. As Alex notes in his piece, there are marvels (and terrors) that escape even the Doctor’s science. But this should be cold comfort for the faithful. Limits to our present understanding do not imply the necessity of a god any more than, 500 years ago, the mystery of lightning or the tides did. And we should remember that no number of holes in our understanding of reality says anything about the veracity of any given religion, because the existence of a question cannot imply the accuracy of a particular answer. Even the possibility that there are fundamental limits to our understanding – that human (or Gallifreyan) brains may simply be biologically incapable of comprehending the true nature of reality – does not mean that it is impossible for everyone. African grey parrots can only count to six, but numbers continue regardless. A deity who lives in the spaces of our ignorance will find its dominion ever smaller, even if those spaces never disappear entirely. The victory of the scientific method is conceded in both the fundamentalists’ ‘creation science’ and the mainstream’s recasting as mere metaphor what they once taught as fact.

Travel with the Doctor brings perspective, the chance to ask questions, to pull back the curtains of both ignorance and deception, to challenge arbitrary power, and to celebrate the facility of a rational mind to alter its view to fit the facts rather than exclude facts to fit with ancient scripture. I suspect an intellectually honest engagement with Eve’s religious conviction would necessarily show it to be the privilege of living in one time and place; of avoiding – or being spared – a real confrontation with the splendour and terror of infinite time and space. Each religion Eve met would – for a time – be vibrant and alive, its followers singularly convinced of its truth and their righteousness; their gods mighty statues, their temples trembling to the echo of their hymns. But then just a short TARDIS hop – a hundred years, a thousand – and she would return to find it all buried in silence: churches mute and crumbling in the lone and level sands, hymns dead words entombed in dusty pages, and once fearsome gods merely curiosities in glass cases.