Join me dear reader, if you dare, on a jaunt to the shadowy world of Doctor Who and evil, satanic rites, and the dark side of the soul. The Doctor’s always battling on the side of good against evil, often in the form of human greed and oppression, misuse of power, or system breakdown. But now and then, the writers veer into a more mythic realm, and teeter on the edge of hell itself. Come with me down into the basement, and take a long look in the mirror Who holds up to life…

The way the show explores the nature of ultimate evil has changed over the decades of Who. But its conclusions are surprisingly similar.

‘The evil that men do’ is well explored in, for example:

- Genesis of the Daleks (1975): eugenics, Nazis, slavery, corrupting power, and endless war. See also the most recent season’s Boom — war is lucrative.

- Vengeance on Varos(1985): voyeuristic violence/reality TV, political decay, and despair.

- The Curse of Fenric (1989): subterranean forces, an Old Enemy from the dawn of time, the evils of war, prejudice, and social stigma. Also, how belief works: others’ belief in us, belief in ourselves, in something bigger.

Doctor Who steers a complicated path; often excoriating about ‘organised’ religion, but more tentative about faith. Compare Fenric with The God Complex (2011); in both the ‘Beast’ recognises real faith, and the Doctor has to break his companion’s faith in him. The God Complex is tricky but worthwhile, especially for one positive portrayal of Islam.

If Who is reluctant to discuss God, it’s less shy about the Devil: who amongst us doesn’t love these two parallel 70’s stories, each featuring:

- A science/religion debate;

- A basement full of hooded Satanists led by someone beginning with M;

- A guest cast from Mummerset;

- An old lady whose witchcraft defences against evil actually work;

- The companion saving the Doctor’s life;

- Yet another myth of aliens interfering with the development of human life;

- And a religious building going up with a bang.

There’s Doctor Who’s iconic Devil in The Daemons (1972), and an unusual one in Image of the Fendahl (1978).

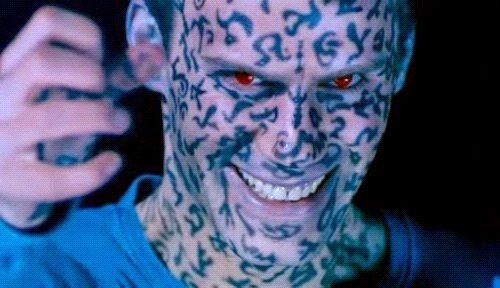

Hair, horns and high-heel hooves…

Or Benedict Cumberbatch’s Mum!

But don’t be fooled by the similarities; one is a UNIT family weekend away in a Dennis Wheatley Theme Park, where the locals commit Morris Dance and the Brig goes off for a beer. The other – Image of the Fendahl – is Daemons done right (ducks hail of protest).

In The Daemons, the Quatermassian ‘Devil’ Azal (you’re never going to get anywhere as a world-conquering alien with a name like bleach or loo paper) is just an alien scientist, disappointed in his experiment. The cult leader knows perfectly well that he’s not really the devil but needs his followers to fuel the necessary power/ego boost (don’t all cult leaders?). He’s not even a ‘proper’ vicar who really believes anything. Miss Hawthorn asserts there is real evil that must not be unleashed, but meanwhile, the villagers are all too easily led. More of this later…

The ‘devil’ is a scientist, and the cult leader is only pretending he’s got religion – sometimes Anglican, sometimes Satanic – and the two people out to stop them both waste a lot of time arguing about whether it’s science or witchcraft that will save the day, until they finally accept they’re two ways of looking at the same forces. And the media stirs it all up and gets in the way. Actually, 1971 doesn’t seem all that far away after all.

In Image of the Fendahl (1977), the source of evil picks on scientists, not religion, and they too are easily led and hungry for power, pushing normal ethics aside in pursuit of their aim. They too are willing to hide a body, sacrifice a colleague, and endanger all life on Earth. How unlike the home life of our own dear fossil-fuel industries… The cult leader is charming and ruthless, his followers so boring and lifeless I can only assume the explanatory lines about drug use were cut in case Mary Whitehouse was watching. Even if ‘evil contains within it the seeds of its own destruction’, the Doctor’s apparent if ‘off screen’ collusion with Stael’s suicide probably had her apoplectic.

These days, despite aggressively secularist culture, Doctor Who is more interested in faith than ever. It’s just less certain of the answers. The go-to 21st Century story for The Devil and All His Works is The Impossible Planet/The Satan Pit, but we find more challenging stuff in Midnight; PageFillers suggests “people’s susceptibility to manipulation in a way that’s all too real and close to home.”

The Impossible Planet/The Satan Pit

Is the Devil ‘real’? The Doctor’s not sure…

TOBY: Just, it was so angry. It was fury and rage and death. It was him. It was the devil.

DOCTOR: If you are the Beast, then answer me this. Which one, hmm? Which devil are you?

VOICE: All of them.

DOCTOR: What, then you’re… the truth behind the myth?

VOICE: This one knows me — as I know him.

Not an answer! Deception always a tactic of The Devil in scriptures.

DOCTOR: That thing is playing on very basic fears. Darkness, childhood nightmares, all that stuff.

DANNY: But that’s how the devil works.

IDA: The urge to jump. Do you know where it comes from, that sensation? Genetic heritage. Ever since we were primates in the trees. Calculating whether or not we can reach the next branch.

DOCTOR: No, that’s not it. That’s too kind. It’s not the urge to jump. It’s deeper than that. It’s the urge to fall!

DOCTOR: You get representations of the Horned Beast right across the universe, in the myths and legends of a million worlds. … Maybe that idea came from somewhere, bleeding through.

IDA: Emanating from here?

DOCTOR: Could be.

IDA: But if this is the original, does that make it real? Does that make it the actual devil, though?

DOCTOR: Well, if that’s what you want to believe. Maybe that’s what the devil is, in the end. An idea.

(They run out of cable. The Doctor is dangling in mid-air. As is the question.)

DOCTOR: Neo Classics, have they got a devil?

IDA: No, not as such. Just er, the things that men do.

DOCTOR: Same thing in the end.

DOCTOR: I accept that you exist. I don’t have to accept what you are, All these things I don’t believe in, are they real? The devil is an idea. In all those civilisations, just an idea. But an idea is hard to kill.

TOBY: I am the rage. … And the bile and the ferocity. …. I am the sin and the fear and the darkness. … I shall never die. The thought of me is forever. In the bleeding hearts of men, in their vanity and obsession and lust …

Midnight

‘L’enfer; c’est les autres.’

‘Windows into the soulless’

Evil rips off the veneer of civilisation and ‘Red Top reader’ vitriol (Val wearing a red top); Russell T Davies called this story ‘attack of the Daily Mail Monsters’.

A grown-up theatre piece which ratchets up the tension by the minute. Professor Hobbes (like the Leviathan author: you might well know the quote, ‘solitary, nasty, poore, brutish and short’) is a mirror for the Doctor: his arrogance, know-it-all lecturing, left shaken by the experience.

HOBBES ‘Well, that’s a relief!’ – The hellish aspects of a long journey: ‘entertainments’, complimentary junk, boredom? Sartre’s Other People?

DEE DEE: We must not look at goblin men, we must not buy their fruits:

Who knows upon what soil they fed their hungry thirsty roots?

HOBBES : She’s not a goblin, or a monster. She’s just a very sick woman.

JETHRO : Think about it though… she was the most scared out of all of us. Maybe that’s what it needed. That’s how it got in.

Fear as the conduit for evil is huge in the Bible – the most common commandment, repeated 365 times, is ‘do not fear.’

DOCTOR: This little bunch of humans. What do you amount to, murder? Because this is where you decide. … Could you actually murder her? … Or are you better than that?

SKY: That’s how he does it. He makes you fight. Creeps into your head. And whispers. Cast him out.

Silence speaks volumes – unspeaking, ashamed, and traumatised passengers. Do we judge them, or show compassion?

HOBBES: ‘I don’t know.’ A moment of grace/growth out of the ashes.

Making fun of monsters at Halloween is a properly biblical idea – ‘the devil can’t bear to be mocked’ so do it. Evil ‘must be fought’, the Doctor says, and proves it can be fought. But not without cost. As these Doctor Who explorations into evil warn us, the hidden depths from which it emerges are not so easily defeated. They are part of culture, society, even economics. Who in all its iterations tells us evil is part of us, but don’t let it have the last word.

***

For the keenest readers, appended below are a few places to begin following this up…

There’s The Gospel According to Doctor Who, and Mister Spence mulling over theology, plus Steve Hackman’s look at Dark Water/ Death in Heaven.

Try typing this Series 8 quote into Google:

‘Do you think I care for you so little that betraying me would make a difference?’

19,300,000 results!

You can watch Professor Holly Jordan’s “The Impossible Pit: Satan, Hell and Teaching Doctor Who” presentation here:

It includes some fascinating excerpts from students own response papers, and demonstrated a lot of valuable pedagogical insights

Worthless Mysteries looked at religion in the show.

Read Andrew Crome and James McGrath’s book, Time and Relative Dimensions in Faith) book here – with a full chapter on The Satan Pit.

Some bloggers’ responses:

The Daemons

Yes, there’s a scientific explanation for the Devil and he’s really just an alien. But, equally crucially, Miss Hawthorne ends up winning her debate with the Doctor over science vs magic by saying that the Doctor’s account of what the Master is doing is wholly consistent with her claim that magic works. This is a story that revels in the gap introduced by the observation that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, using this to assert that traditional occultism is in fact extremely advanced technology. This means that the creature the Doctor meets may just be a powerful alien, but he’s also genuinely and truly the Devil.”

From Erudutorum Press.

Surprisingly maturely, a television show for kids doesn’t reduce the science versus magic debate to a right/wrong binary, but calls into question not just the terms of the argument but the audience’s own preconceptions … It invites the viewer to actively question and participate in the debate, rather than to blindly accept that science is right because it’s, well, science, and that’s that – because then you’re just replacing one form of historically lazy, unthinking doctrinal suspension of criticality for another.

From the defunct Kasterborous.

[I]f the Master is a Fake Vicar, then the Doctor is the Science Vicar, the one who has the Truth that science answers all, and is the answer for everything. Which of course it isn’t. Just like Journalism, Science is no longer about the objective search for truth, it’s now about seeking out evidence to support your worldview, regardless of where the actual evidence may lead.

From WhoFlix, sadly now private.

The Satan Pit

The Impossible Planet is a challenge to the traditional sci-fi way of thinking about the universe as an inherently rational or at least coherent place, but doesn’t set the ontological conflict in an either/or framework. The technology that traps the Beast is explained as traditional technological science, and the Beast explicitly identifies himself as a supernatural/mystical being. But the Doctor and Rose don’t choose either of these sides.

The Beast identifies itself as the literal Devil, and certainly was a powerful enough force of malignancy that the ancients went to a lot of trouble to imprison it, but I think the story itself does not buy its claims for a minute.

From Erudutorum Press.

Midnight

[T]he unspoken implications are even worse – all of the Doctor’s fellow travellers sense it, but it’s really only the Doctor himself who recognises exactly what the creature is doing. Somehow, through their language and mannerisms, it’s assimilating their voice, their behaviour, their essence, their very being.

From Probic Vent.

[H]ow much the unseen knocking that jumps on board via Sky is a real presence and not just free burning good old human paranoia and hysteria…I like that it’s left unclear

From November 32nd.

[T]he sad truth is that it isn’t the nice people that are listened to in out of control situations like this.

From Doctor Oho.

I prefer the interpretation that has the passengers’ worst aspects coming out in a crisis, that their (shared) evil is theirs and theirs alone. The episode doesn’t quite let us though.

From Siskoid.

It’s about predatory forces of will, the powerlessness of the individual and the people’s susceptibility to manipulation in a way that’s all too real and close to home.

From PageFillers.

It is not that the hero is flawed because he’s fictional. It’s that we are all flawed because we are not.

Jane December comment on Eruditorum Press:

The bus tour company is named “Crusader,” invoking another religious connotation — the Crusaders undertook military expeditions to wrest control of the Holy Lands. Ergo, Midnight is similarly a Holy Land, which has (this time) been occupied by a capitalist force; it is “holy” in the alchemical sense, that it reveals the nature of the people aboard the bus to themselves and each other. In this context we can slot in the Lost Moon of Poosh — the moon representing the subconscious, in juxtaposition to the consciousness of the sun — what the characters have been repressing comes to the surface.

The manipulation of public fear, by such disaster capitalists, to erode civil liberties is one that taps into our very primal reactions to ‘otherness’. The strangers who deplore our foreign policies and the strangers who migrate to our borders are, deep down, tokens of our own fractured human psyche. There is a single moment in Midnight that tells you all you need to know. When Val Crane spits out venomously ‘Immigrant’ at the Doctor then we know that as a human being, and like most of us, she’s reacting to the strangeness of the ‘other’. Here she’s attacking the Doctor who can’t tell them his real name and is far too clever for his own good, and dealing with her xenophobia with one of two choices. Either you try and understand and accommodate this experience of strangeness or otherness or you repudiate it by projecting it exclusively onto outsiders, in this case the possessed Sky Sylvestry and the seemingly arrogant and alien Doctor. By having Val utter that one word, Russell T Davies encapsulates the arid mind-set of millions of Daily Mail readers.

Happy Halloween, everyone…!