I just had a quick plumb through the DWC archives, and have calculated that I’ve written the words “They say you should never meet your heroes” no less than six times. It is a well-worn cliché and I probably use it too much, but that doesn’t stop it being true. Meeting a hero reduces them; in turn they are instantly flawed, vulnerable, and (if you catch them on an off day) possibly a little abrupt. That’s fine, if the meeting is not just a chance encounter – a double-take in a theme park, a chat on the underground – but rather the beginnings of a friendship, a chance to get to know your icons as people. But that rarely happens: instead these moments are fleeting and hollow, taking place at the most inconvenient of times and leaving you with the impression that you’ve exchanged one view for another, and not in a good way.

But what if meeting your heroes were not something to be avoided but – through the medium of time travel – actively exploited? What if you could strike up friendships, influence choices, weave in and out of the important moments like a temporal loom operator? What if you determined that by meeting your heroes you could shape who they became?

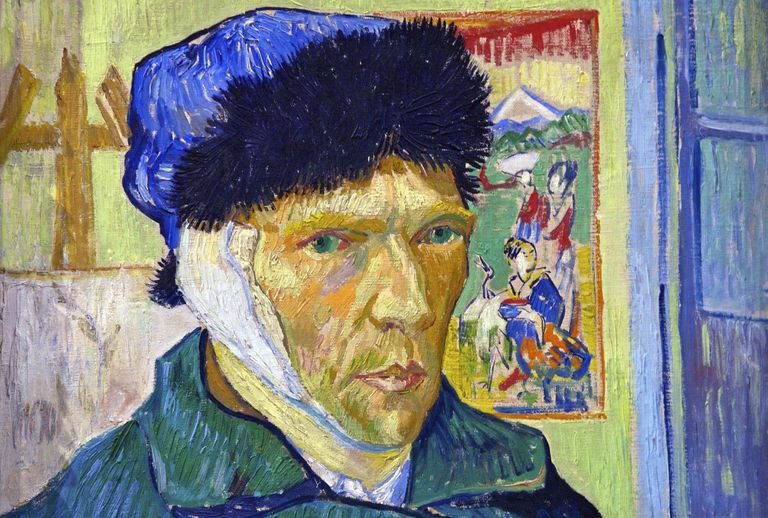

That’s the question posed, and more or less answered, in After Vincent, the somewhat ambitiously subtitled “Series One Book One” in the newly-launched Chronosmiths Chronicles – the work of Paul Driscoll (The Black Archive, Master Pieces), who creates a world where what-ifs become not just a thematic motif but also a McGuffin. Set in the distant future, it follows the adventures of a quartet of time travelling adventurers known as the Chronosmiths, war heroes turned interstellar Ronin, seeking employment (and, we sense, a form of redemption) in a universe that does not understand them, on a world where the principal religion revolves entirely around the worship and adulation of Vincent Van Gogh.

Things get off to a shaky start. The first 50 pages unfold in a maelstrom of info dumps, characters and contexts piled on in an uneven mess, like the Double or Drop game they do in Crackerjack. It’s one thing to introduce four distinct time travellers who have escaped a war in order to establish a new life. It’s another to tell us their backstories, and then admit that these backstories are imagined because of a memory wipe, and that the universe they’ve escaped into is a bit like ours but set in the future where non-humans are segregated and there’s a religion with its own history and problems and the agency they’re working for has a set of rival mercenaries on its books, all with their own backstories, and then there are particularly vicious aliens that are known in both universes and they may have secrets… it all comes more or less at once, in a torrent, and it’s impossible not to feel overwhelmed.

That’s assuming, of course, that you’re coming to this as a first time reader who hasn’t experienced the Chronosmiths in their previous adventure, Gallifrey, which saw the central characters abandon their home and flee to a new universe with new identities, a sort of witness protection programme in space. While ostensibly a fresh set of adventures, this is clearly meant to be a follow-on of sorts, and like Harry Potter’s resurrection stone, it opens at the close. Is it possible to enjoy After Vincent without having read Gallifrey? Yes, but you need to take comfort breaks.

Once everything settles down and we (more or less) know who everyone is and what they’re doing, the story kicks into gear. And it is a good story, despite being occasionally convoluted and rather too long, exploring both key events in Van Gogh’s life and asking the question of how he reached the heights of genius for which he is now renowned. Was it simply a question of seeing things differently? Or were there outside forces involved? The answer turns out to be a combination of both – although the lesson learned, in this case, is that tinkering with the timeline is seldom as straightforward as you think it will be, and that, were there no Vincent Van Gogh, it would have been necessary to create him.

The notion of Van Gogh the artist versus the faith he ultimately inspired is a key theme throughout – and under Driscoll’s direction, everyday items take on iconographic symbolism. Straw hats are worn by designated authority figures. Sunflowers emblazon the walls of the Yellow Temple, while Van Gogh’s smoking skull is used for far more nefarious purposes. And the coffee and black bread of which he was so allegedly fond becomes a communal sacrament: wafers and wine, dressed up for Eastern Europe. It is purposely outlandish, but not beyond the realms of credibility – and it prises at the lid of an ecumenical can of worms that, at least for the purposes of this review, would be best left shut.

That’s not to say that this is anti-religious novel. Goghism is a clear parallel for Christianity, with its distortions and evangelical fervour, but Driscoll stops short of outright condemnation: “There are plenty of good things in this universe,” one character notes, “that have been founded on a lie”. This is a book about a man who uses a religious framework for his own ends – to say more would spoil things – but the moral maze is complicated and the author is sensible enough to leave things open-ended. We know what we think, but we’re not entirely sure if it’s right.

The narrative takes the portrait of the artist as a young god to an obvious extreme, but for anyone who’s seen Doctor Who Series 5 we’re in familiar territory. Curtis’s Eleventh Doctor story is a clear influence on Driscoll (despite his claims that it wasn’t), and even if he spins the narrative in an entirely new direction it would be foolhardy not to acknowledge it. More to the point this is a book (and, you suspect, a series) about characters who are like Time Lords but not exactly like Time Lords, with a ship that is basically a TARDIS with a functioning chameleon circuit. Hence there are some entirely deliberate and frequently eye-rollingly silly references (binary cardiovascular system? Check. Time vortex rites of passage? Check) but this is explained away with the single use of the word ‘multiverse’, which gets everyone nicely off the hook.

The story is complex and multi-layered with everyone off doing their own thing, but what really works is Driscoll’s ability to craft individual scenes – something he does particularly well, and it’s a shame that the paragraphs of social commentary occasionally detract from it. The ideas come at the speed of a juggernaut, or Van Gogh on one of his manic days. Refugees and border checks! Mental health issues! Religious fundamentalism! Immigration and racial hatred! Poverty and the breadline! None of it feels shoehorned, but a lot of it feels under-explored, and you get the feeling that a bit of restraint would have resulted in a more streamlined, but ultimately satisfying experience.

As it turns out, After Vincent is at its best when the characters are just talking. Driscoll has clearly taken the time to flesh them out, and the offshoot is a bunch of believable protagonists and supporting turns (including a decently rendered and at times almost sympathetic villain). There’s a moody but astoundingly competent engineer, a superpowered academic who deliberately hides his light under a bushel, a shrewd and not-entirely-trustworthy politician… certain clichés are mined but nonetheless, they all breathe, and most of the people who turn up feel refreshingly three-dimensional. When they’re not weighed down with exposition, and allowed to simply chat, the universe Driscoll has created finally solidifies and the dialogue sparkles like a good episode of Blake’s 7. Although goodness me, you wish he’d drop in the odd semi-colon. Even an em dash would work.

Nonetheless, this is a promising start. As the Chronosmiths head off to other adventures, unsure as to whether they can really trust each other or even themselves, we’re graced with an unfolding world which teases substantial and (hopefully) rich rewards when the author eventually shows his hand and the truth comes out. Like the characters who inhabit the Hexachron, all fighting their own history (when they’re not fighting with each other), the Chronosmith Chronicles has the potential to forge its own brilliant path – provided it can divest itself of the inevitable shackles that any Who-like series is going to find wrapped around its waist. Maybe we’ll see that in Book Two.

The Chronosmith Chronicles: After Vincent is out now from Altrix Books.