Picture it: the elegant, immaculately shipshape bridge of an interstellar cruise liner. In the distance, the radar pings, and klaxons hail a warning. Geoffrey Palmer stands by a bank of blinking lights, levelling a ship’s issue revolver at an incredulous Russell Tovey. “They promised me old men,” he mutters. A tear glistens at the corner of his eye. “Sea dogs. Men who’d had their time. Not boys.”

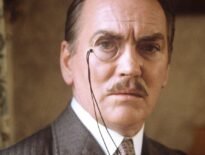

There is a great sense of character in that wrinkled brow. Character in the dramatic sense, that is. The furrowed creases, the permanently downturned jaw, almost calling to mind the image of Droopy the basset hound: Geoffrey Palmer, taken from us at the not inconsiderable age of 93, was one of those people who seemed to carry the weight of the world on his shoulders, at least aesthetically. And then there was the voice – whether sipping sherry in suburbia with Judi Dench or wandering the halls of Westminster, his dry, deadpan delivery is instantly recognisable, and he’s become one of those people you simply know, whatever he’s doing.

That’s not to say he’s ever been a victim of typecasting. Born in 1920s London, he took to the stage (initially behind it, as a trainee stage manager) after national service, eventually breaking into television a decade later. His first roles of note were in The Army Game, alongside Harry Fowler, Dad’s Army’s Frank Williams, and a certain William Hartnell. Palmer appeared in 20 episodes in over a dozen different roles, ranging from soldiers to government officials to media personalities. 150 episodes of The Army Game were produced: of these, only a third are thought to have survived.

While he would make his mark in several prominent and well-established classics, it is a testament to Palmer that you don’t actually remember just how often you saw him on screen. Small roles in the likes of Clockwise (1986), Paddington (2014), and Ashes To Ashes (2008) would frequently cast him as authoritarians or statesmen, something he did extremely well – he played both Stanley Baldwin (in W.E., 2011) and Richard Warren, personal physician to George III, in The Madness of King George. But his C.V. is an absolute smorgasbord, ranging from The Avengers (in which he appeared three times, playing separate roles) through to Morse and Bergerac by way of Whoops Apocalypse. You name it, chances are Palmer’s been in it, and if he hasn’t, he was probably on the shortlist at least once.

It is for sitcoms that he will arguably be most fondly remembered, appearing opposite the likes of Leonard Rossiter (The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin) and Wendy Craig (Butterflies). Indeed, his role as the belligerent, butterfly-collecting Ben – described as ‘pleasant’ by his screen wife – is an archetype for the straight-laced and slightly dull middle-aged man, who eventually morphs into the slightly grumpy old man he later became in As Time Goes By. Ria spent years of frustrated discontent in her marriage to Ben, and yet she could never quite bring herself to leave him: who else would tolerate her cooking?

Perenially keen to flex his dramatic muscles, Palmer nonetheless knew that steady TV work was a sure way to earn a living. Besides Butterflies, the ’70s and ’80s would see him turn his hand to several classic British sitcoms – including The Goodies and the final episode of Blackadder Goes Forth, in which he is an obvious choice for Douglas Haig. He also appears as the hapless Dr Price in a memorable Fawlty Towers episode, The Kipper and the Corpse, in which his role is to play the straight man who spends an eternity waiting for his sausages, while John Cleese spends most of the runtime hiking a dead body up and down the staircase and waving a fish.

As Time Goes By remains a career highlight. Between them, Dench and Palmer took the idea of twilight love affairs to heights not seen since… well, Cocoon, probably, but there’s no denying the show was tremendously successful. Reunited after decades apart (due to a bit of a cock-up on the postal front), Jean and Lionel enjoyed a tender, if occasionally bumpy romance, finally marrying in the fourth series. Off-screen things look to have been a little less twee – Dench describing her co-star as both “a master of comedy” and also “the naughtiest man I ever had the pleasure to work with”. (Dench and Palmer would be reunited on the big screen on a number of occasions, notably in the likes of Mrs Brown, but perhaps most memorably in 1997’s Tomorrow Never Dies, where they argue like exactly the sort of married couple they’d already played on TV.)

He continued to appear on screen and on radio for most of his life, whether it was for lending his dulcet tones to advertising (he it was who told us to Slam In The Lamb, and yes, that’s his voice you can hear saying “Vorsprung durch technik” on the Audi adverts). Palmer’s talent for befuddled grumpiness meant that some of his best work inevitably involved children, whether it was fishing with a disinterested Thomas Sangster in Stig of the Dump (2002), or trying to read a newspaper while a miniaturised James Bolam reaches out to his inner child (Grandpa In My Pocket, 2010). He was a master of narration and voiceover, turning his hand to several Roald Dahl audiobooks (including Revolting Rhymes, in which he and Pam Ferris make a delightful double act) and the 1990s Mr Men TV series. Perhaps inevitably, his voice may be heard in the transitionary moments of the BBC’s Grumpy Old Men.

He would appear in Doctor Who three times. Indeed, Palmer joins the roster of a handful of actors who appeared in both the Classic series and its contemporary revival – a list that also includes Clive Swift, Garrick Hagon, and two of the Troughtons. Palmer’s first appearance was in Doctor Who and the Silurians, in which he played Edward Masters (or Frederick Masters, depending on what you’re reading), the unfortunate Under-Secretary who almost unleashes a plague upon London, despite insisting to everyone that he’s ‘fine’. There is something quintessentially British about this, not least because Masters’ final moments see him struggling for breath while pressed up against a railing in the middle of Shepherd’s Bush. There are worse ways to go, and at least he didn’t bite the head off a bat.

A couple of years later, he would show up again – this time in The Mutants, in which he played the Administrator, the same sort of no-nonsense authority figure who’s destined not to make it to the end of the story (or, in this instance, the end of Part One). His sudden assassination is the catalyst for much of what follows, although Palmer’s death scene adheres to the typical Whovian convention of the rabbit-in-headlights stare as the camera zooms in, followed by the slow drop to the ground. And if you rewind a couple of years to that Shepherd’s Bush underpass, he bites the dust in much the same way. Do they teach a masterclass in these things, or was it something thrashed out by the unions?

Thankfully, by Voyage of the Damned, things had been shaken up a bit. We don’t actually see him die this time around, but Palmer invests Captain Hardaker with a gravitas that makes him an unfathomably sympathetic character, despite the fact that he’s about to commit mass murder and wipe out an entire planet. The role of character-as-plot-point is thorny ground, but Palmer makes the most of his limited screentime and some decent dialogue, and the result is one of Doctor Who’s most memorable cameos. When Hardaker admits he’s doing all this for his family – Walter White in space – it’s easy to understand what might have led an elderly sailor to go out in a (literal) blaze of damnation, and a small part of you almost admires him for it.

“Why do I get the feeling you’ll be the death of me?”

Off-screen, Palmer’s life was a good deal happier and rather less turbulent: he married health visitor Sally Green in 1963, and they remained together until his death. They produced two children, daughter Harriet and son Charles, a director who counts six episodes of Doctor Who (including the Human Nature / Family of Blood two-parter and the exemplary Eaters of Light) among his portfolio. Palmer Sr. kept his private life notoriously cloistered, although it is known that he was a keen fisherman (a fly rod was his chosen luxury on Desert Island Discs, along with The Oxford Book of English Verse; his musical choices included Brahms and Fats Waller).

Dry as a Sauvignon Blanc, world-weary as a 1940s gumshoe, Palmer left an indelible mark, and will be much missed. But perhaps we should stop thinking of him as grumpy: he was protean to a theatrical fault, never content with simply playing himself. His final role is in the as-yet unreleased An Unquiet Life, in which he plays Roald Dahl’s Repton headmaster – a man renowned (at least according to Dahl) for preaching about mercy and love in between thrashing his students with a cane, which should suit Palmer to a tee. If he became known for dour, easily-irritated characters, then that’s a compliment, not a defining characteristic, and it is in this frame of mind that we mourn one of our most beloved and versatile actors, reserved and dignified, perhaps even ostensibly a little aloof, but adored by the people who knew him and seemingly never afraid to roll up his sleeves. “I’m not grumpy,” he once said. “I just look this way.”