This was going to be one of those travel items. You know the sort of thing: a review which isn’t exactly a review, with a sentence about prices and opening hours pasted in bold at the bottom, linking to the company’s website, or somewhere else you can buy tickets. That was February, back when we were allowed to go places but it was being mooted, albeit with more subtlety than was arguably needed, that perhaps we should not. That was a simpler, more innocent time, when Covid-19 was still media hype instead of a game changer that got us where we are. Like the pre-invasion Surrey of War of the Worlds, life continued just as it always did; certain words – furlough, lockdown, social distancing – were yet to enter common use, and no one was panicking, except the Chinese. If you sit in a dark room for long enough, you can still remember it.

The months shift and everybody stays indoors, but I still have the pictures. It seems right to mark it somehow, this foray into the world of a troubled recluse, a man who sold a single painting within his lifetime, only recognised as a genius long after he was dead. His paintings are scattered far and wide, although a few of them – Wheatfield with Cypresses, Van Gogh’s Chair, The Sunflowers – hang in the National Gallery. My first encounter with The Sunflowers was 12 years ago, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (And yes, we did run up the steps. I didn’t want to, but I wasn’t about to be outdone by a woman in her fifth month of pregnancy.)

The Philadelphia Sunflowers is yellow on blue, giving off an almost pastel sheen, and hangs unceremoniously on the wall in a room on the second floor (first, if you’re British). In 2008, it was worth $97 million dollars, according to the security guard standing nearby, who might just as easily have plucked the figure from the air like a bullfrog lancing a fly. That evening I’d recounted the thrill of discovery to my American colleagues, specifically a Pennsylvania local named Laura, over dinner. “It was just a complete surprise,” I said. “Seeing the original. Not just the sunflowers. The. Sunflowers. I don’t know. There was something amazing about it.”

Laura chewed on her steak and looked at me. “You do know he painted, like, seven of them?”

That was then. This is now: or, to be specific, February; I’m a little older and none much the wiser and my family and I are treading down the South Bank towards Doon Street, where sits King’s College and an unimpressive looking tent. We’re here to see the Van Gogh Experience, which promises an up-close-if-not-exactly-personal encounter with the man behind some of the most famous paintings in history. People cannot always visit the paintings of Van Gogh, the Experience creators argue, and so by means of holographic projection and a couple of 3D printers they have devised a means of bringing the art to them. It is expensive – there are six in our party – but we’ve managed to wangle a concession. Besides, Edward’s just done The Starry Night at school, so it’s educational. At least that’s what I’m telling myself, and my accountant.

Modern art starts with Matisse and Picasso, who had a love child and named him Lichtenstein. That isn’t really true. Or it is, depending on who you ask. I recently attended a webinar given by Andrew Spira, who suggested that much of the value of what we now call art stems from the industrial revolution, which made mass production much easier and devalued the skillset of master craftsmen, placing greater emphasis on the image they were copying. Then along came the Impressionists with their paint-anywhere mindset and the Surrealists with their lobster phones and eventually the Post-Modernists, wherein the process becomes the art, or at least a part of the composite. Pollock doesn’t just drip; he drips in a meaningful way. Supposedly.

Lately I’ve come to the conclusion that my appreciation of and interest in art probably mirrors that of many Doctor Who fans I come across. As if drawn like a magnet, I tend to focus on the recent stuff, if by ‘recent’ you mean anything from last century. I’m reasonably well-versed in Dali, for example, but what I really enjoy are the colossal installations that take up entire rooms at the Tate Modern, or the 20ft canvases of contemporary artists whose raison d’etre it is primarily to splodge, but splodge with purpose. And there is a purpose, even though we can’t always see it – still, I worry that I’m missing out. I can understand, for example, why Gilbert and George seek refuge in shock and awe, and why some minimalism is about the space around the object and some of it is about the object itself. But I couldn’t tell you how they relate to Caravaggio, or Rembrandt (yes, I know he’s a pioneer of the Dutch Golden Age, but I can’t name a single one of his works). I recognise Constable’s position as a landscape painter par excellence, but I don’t know anything he did except The Haywain, and even then that’s only because my grandparents had a framed print hanging in their front room.

Does it matter? In all likelihood, it probably does. Or at the very least it dilutes the experience, makes it somehow less, like watching an episode of Morse over the ironing board. You miss things. On the other hand, the first step in plugging the knowledge gap is recognising that the gap exists. It helps that the galleries I go to are thankfully free of smart-alecks, in a way that Doctor Who groups are not. I’ve never had anyone come up to me while I’m admiring a painting and tell me that yes, Francis Bacon was a genius, but did you know he was really aping Masaccio with this one? And as for his views on Goya, well. Don’t get me started.

Back in London, the sign on the outside reads “Meet Van Gogh”, but – perhaps mercifully – there are no bearded actors awaiting us within the marquee, ready to thrill the audience with scripted exchanges about perspective and light. This is a tale told entirely through the medium of prerecorded narration, the audio filtering through your headsets when you walk onto certain hotspots: there is no more fiddling with buttons to find different tracks; it’s all done for you. Sometimes the audio is timed with the visuals on a screen in the area where you happen to be standing, giving disembodied voices a face and a presence. It works, more or less – it’s not always clear where the hotspots actually are, which means you can be halfway through a retrospective of Van Gogh’s time in Paris only to suddenly hear that lecture about his use of colour for the third time in almost as many minutes, all because you’ve happened to stray three inches too far to the left.

Things start badly: around that first corner is an introductory video hosted by Axel Ruger, the (until recently) General Director of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. He pronounces it ‘Van Go’. I’m not sure whether this is for the benefit of the Americans, or whether I’ve simply been misinformed, but I was reasonably confident that ‘Van Goff’ isn’t exactly correct and ‘Van Go’ is worse still. Supposedly the proper pronunciation is closer to ‘Ffan Hoch’, although that’s really something only the Dutch can pull off with any real sense of panache, and I suspect my feeble efforts are probably treading the slender tightrope between doing as the Romans do and lapsing into brazen cultural appropriation.

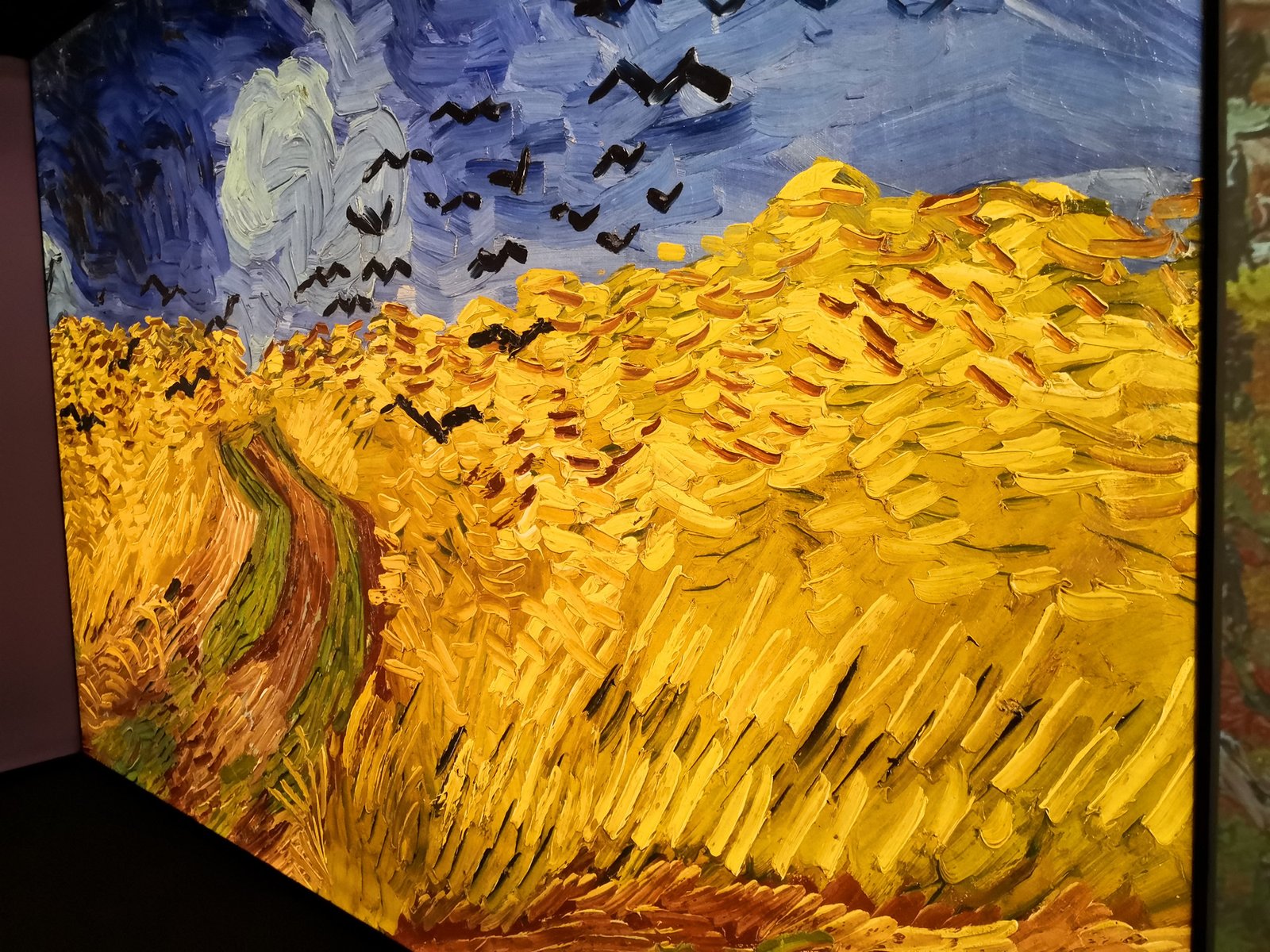

My children (who’ve long since referred to him as ‘Van Go’ specifically to wind up their poor father) are predictably smug, and elect to tease me about this – and Richard III’s mythical hunched back, another pet hate – as we wander through. You start out in a sun-drenched cornfield, a grand expanse of yellow and blue that spans three walls. There is a mournful elegy, the sound of birdsong, and then a single gunshot, followed by the fluttering of wings and the cawing of crows. It’s an impressive vista, or at least it would be if there weren’t people standing all over it. Why do you think there are benches?

But there is a hushed silence, broken only by the sound of footsteps and whispered conversation and, occasionally, the scratching of pens. You feel like you’re in the presence of something important. A similar vibe can be found in the Hockney 1853 Gallery in Saltaire, a former mill converted into a vast repository for Bradford’s favourite son (apart from Zayn Malik, anyway). Walking through there is an almost religious experience, akin to walking through a cathedral. This isn’t quite like that, but it does feel a little like that moment in a festival when you wander away from the crowds and find yourself at a particularly well rendered art exhibition, perhaps with a workshop going on in one quiet corner.

I say silence, but perhaps that’s the earphones. The Van Gogh Experience offers timed tickets to ensure there is no overcrowding, which means plenty of room to move around – which is good, because after those early, hushed rooms, you enter the cafe area, which (as it turns out) is where all the kids have been hiding. Indeed, this is a place geared perhaps more for families than for connoisseurs – whether it’s the peep-hole photo opportunities in the entrance lobby (become the eye of a sunflower while you wait!) or the interactive lessons on self portraits and the science of restoration. Even the wall displays and 3D printed recreations are festooned with notices reading “FEEL FREE TO TOUCH EVERYTHING”.

Looking around this bustling recreation of rural France, it’s clear we’re in the epicentre of the Experience. There is a hay wagon, upon which two of my children are currently clambering. A blown-up rendering of one section of the Harvest at La Crau designed to give an idea of the texture of paint. A motion sensor colour splattering exhibit that doesn’t really work. Over to the side, you can take a selfie on Van Gogh’s bed. After watching Tony Curran cry himself to sleep in that Doctor Who episode it seems almost grotesque to get in line. We do it anyway.

“Give me a moment,” I say to Emily. “I need one of the room on its own.”

“Why do you need one of the room on its own?”

“I promised Phil a write-up.”

She rolls her eyes. “Honestly, we can never just go anywhere, can we?”

Behind the facade that is the Arles house you discover a shadow puppet play that re-enacts one of the darker moments of Van Gogh’s life. We do not see the severing of the ear, or hear his cries of torment: only the voices of Van Gogh and Gauguin, arguing over money. There are smaller rooms, intimate and claustrophobic, charting his instutionalisation and mental decline, the white walls peppered with landscapes. For the first time, you get a sense of the monster that hid inside Vincent’s head, one far more dangerous than a giant invisible chicken, and far more distressing… and then, and then, rounding a corner, the Starry Night takes up an entire wall, and you’re faced with the paradox to which Bill Nighy refers at the end of Vincent and the Doctor, wherein pain is transformed into joy.

Nighy turns up at the end: a showreel plays looped highlights of Van Gogh’s depictions on film and TV, in which Doctor Who features prominently. And then you walk through an overpriced gift shop and out into the sunshine, and it’s hard not to feel just a little bit cheated. Perhaps it was inevitable: a projection, irrespective of size, is still a projection, and it’s impossible to forget as you wander the tented interior that what you’re looking at is a recreation, rather like one of those virtual gallery tours that everyone’s been doing these last months. There is a sense of a life, and there is a story that’s being told, but it is a story told in fits and starts, retreads and narrative side steps, like a joke you can’t quite remember. As much as you want to be drawn in to the 10ft high panoramic vistas, you’re not wandering in a French wheat field – just a facsimile of one. Matters aren’t helped by some questionable production choices, chief of which is Van Gogh’s cultivated BBC English voice, which sounds like a cut price John Hurt.

It’s all a bit prosaic, an exercise in clunky, aesthetically charming bluster, lacking any real sense of coherence. Some experiences have the lights up but give you a smorgasbord of buttons and switches; others are very much hands off, but manage to drop you in the thick of the action. The Van Gogh Experience doesn’t manage either, at least not successfully, and thus straddles an awkward line between interactive and immersive, neither one thing or another, undefined and lukewarm. And yet we did emerge into the February cold with a greater appreciation of the artist and what made him tick – this wild man of Provence, this misunderstood master, this man out of time. Scenes from Vincent had played in my head all afternoon, and perhaps after a couple of hours in a darkened tent I understood them just a little better. It had been an expensive day, but perhaps not a wasted one: short of actually visiting a set that’s presumably long dismantled, this might be the closest you can actually get to wandering the wondrous, colour-drenched world of Van Gogh, even though there’s absolutely no sign of a Krafayis.

But then, of course, there wouldn’t be.

The Meet Vincent Van Gogh Experience is currently closed, but it will hopefully tour next spring. There, I managed a sentence in bold.