“Psst. Oi mate.”

“Yes? What d’you want?”

“Want a video?”

“… Depends what’s on it.”

“Cybermen. Tobias Vaughan. The Edge of Destruction in Arabic.”

“No way!”

“Straight up. Would I lie to you?”

“What’s the exchange?”

“You see me right with your camera copy of Terror of the Autons and I’ll bung in The Sunmakers gratis.”

“Four episodes or edited?”

“Edited, mate. No titles. What do you take me for? You want complete episodes, you have to bung me your Colony in Space as well.”

Yes, such were the conversations that were not really had in the Seventies and early Eighties in pubs and local groups up and down the UK. I speak of a time when Tom Baker was the Doctor and Graham Williams the producer; when Time Life television had sold his first four seasons to PBS stations in the USA; and Australian television endlessly reran the Pertwee and Baker episodes. This was the time when VHS and Betamax video recorders were penetrating suburban homes; when old stories in the UK meant two summer repeats of stories from the season that had just finished; a time before John Nathan-Turner sanctioned repeats featuring the non-current Doctor on BBC 2; a time even before Queen Xanxia ruled Zanak and Mrs Thatcher ruled Britain, and long before you could buy The Brain of Morbius and Revenge of the Cybermen on commercial VHS. It was a dark time, of endless rain and fog, when fans scratched secret signs on doorposts and, after dark, took delivery of a brown paper bag from a certain man in an anorak who did not speak but nodded and went on his way into the night. Furtively, the fan checked the contents of the bag: a Boots VHS video labelled, The Daemons…

This was the time when Simon (my twin brother) and I were teenagers and the 1970s spooled out on the cosmic video tape of life. It seems strange to think of now, when we can watch any story we want just by clicking a few times on a mouse on Britbox, or by slipping a disc into a slot, but for British Doctor Who fans in the mid-Seventies, you just couldn’t access the old stories. We only knew what happened in, say, The Dalek Invasion of Earth because we’d read the novelisation by Terrance Dicks (I read it in hospital after an appendicectomy and took a heck of a long time to finish it because I was full of anaesthetic). We’d also seen the pictures in the 1973 Radio Times Doctor Who Tenth Anniversary Special: these, and the Peter Cushing movie, which aired every couple of years on Saturday morning BBC TV, helped the imagination with the imagery. The Target novelisations were our main source of revisiting old stories, which explains perhaps why they are so loved by fans who grew up with the original series.

Then came… the cassette recorder. Miracles of technology, the cassette miniaturised the reel-to-reel tape recorder and sealed the spools in a credit-card-sized plastic envelope of fun. Cassettes were affordable even when you didn’t have much pocket money and, if you dangled the microphone next to your television speaker, you could record the sound of an episode of Doctor Who. No pictures: just sound. O rapture! I think Simon and I started doing this in 1978, as my almost total recall of dialogue from The Ribos Operation and the Key to Time season dates from endless listenings to the recordings. Of course, you had no idea what was happening during the incidental music and sound effects sections: these played like happy intermissions while the dialogue paused. At least it gave you a chance to appreciate Dudley Simpson’s music. The only issue was the microphones recorded the buzzy television speakers of the period so every episode played through a 25 minutes raspberry of static.

PHHHHHRRRRRRRRRTTTTTTTTTTTT and now on BBC one, Tom Baker stars in a new adventure for Doctor Who PPPPPPPPPPPHHHHHHHRRRRTTTTTT dumble de dum! Dumble de dum! Dumble de dum de dum WHOOOOOOOOOOO OOOOOOOOOOOOO PHHHHHHHHHHHHHRRRRRRRRRRRRRTTTTTT…”

You get the general idea.

Time-Life television offered this brochure to American PBS stations in 1978: they syndicated Tom Baker’s first four seasons.

Most fans recorded Doctor Who onto cassette in the later Seventies. The Doctor Who Appreciation Society even sold little cardboard covers for your cassette boxes, with the old shield logo on the front and space for you to write the title in tiny letters. Swapsies were common. A few years later, there would be problems of compatibility in exchanging videos with American fans, but cassettes were compatible on both sides of the Atlantic. Simon and I had some kind and generous pen pals who sent us cassettes of early Tom Baker stories, and we listened, open mouthed, to Genesis of the Daleks and Pyramids of Mars – stories we hadn’t seen for three or four years which, when you are 14, seems like half a lifetime ago. These American recordings had additional, twinkly incidental music which I initially took to be extra bonus material by Dudley Simpson but eventually realised were the leads-in to advert breaks (“Doctor Who – back in a moment!”). Each episode was intriguingly introduced by a voice over from gravel-voiced American actor Howard da Silva, who welcomed in a montage of clips from the episode we were about to see – or hear, rather.

“On a distant planet, a giant sandminer combs the desert for minerals. Inside, it is fully manned by robots, with a skeleton human crew. But when the DOCTOR arrives, with LEELA, his new traveling companion, they seem to bring catastrophe…” Cut to Uvanov screeching, “What are you doing on this mine?” and Tom Baker’s unfussed response, “Well, we’re travellers, we came here by accident.” Back to da Silva: “A human overseer finds out that the Doctor and Leela are not responsible for the deaths. Unfortunately, the secret will remain his…” Cut to Chub the crewman, “No, there, you electronic moron… what are you doing?… No! No! Get away from me! ARRRRGGGGHHHHHHH! AIIIIIIIIIIIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!” And the end of each episode would cut from the end title’s scream to clips for the next episode. Da Silva on Leela facing a robot: “But if the huntress cannot defend herself… who can?”

Are there any American fans out there who remember the da Silva voiceovers? These were added to each episode when Time Life television distributed Tom Baker’s first four seasons in 1978, presumably to bump up the running time from 25 to 30 minutes, and many Stateside fans hated them – not least because several seconds of action in each episode were pruned to make way for the narration. But to a British fan in his teens back then, the voiceovers were exotic and exciting. (Look, it was the Seventies, mate. We had to take what excitement we could.)

Video recorders were starting to appear in the mid-1970s, usually in the clunky and unreliable format of the u-matic system, whose cassettes were the size of a brick and only ran for (I think) one hour. They were impossibly expensive for most homes and tended to appear only in schools. Simon and I once bought a u-matic cassette for school and asked a friendly teacher to record episode one of the new television version of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy for us. I think he did so, but we never saw it: I think we baulked at spending more time in school than we had to, even to watch more Douglas Adams, and the TV version wasn’t as good as the radio version anyway. We eventually donated the tape to school.

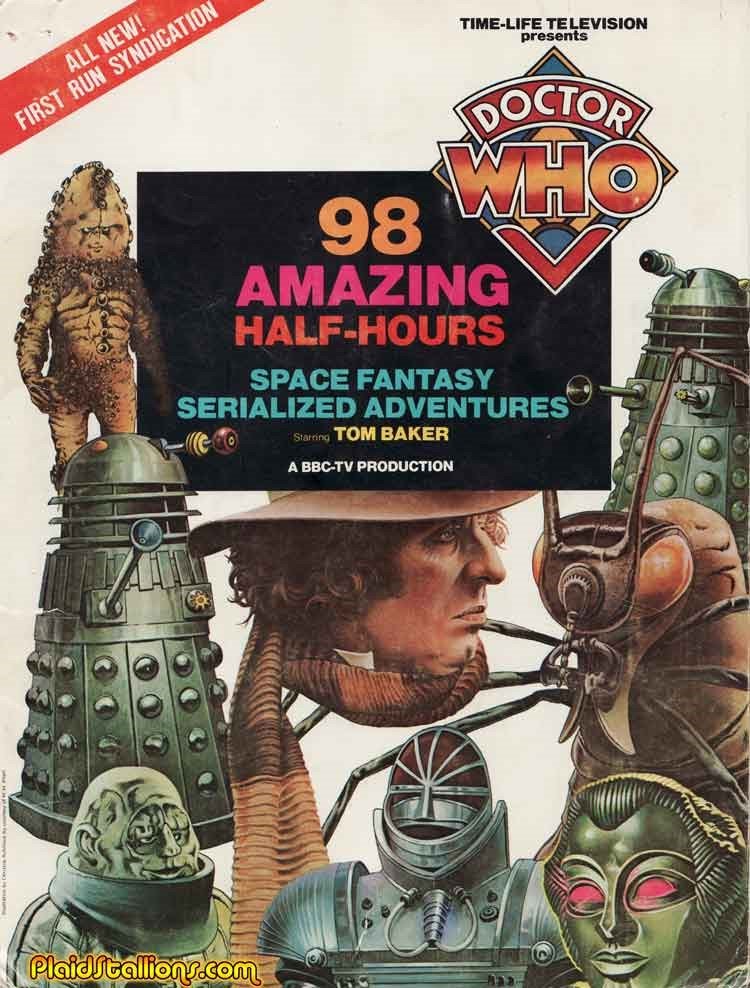

Not quite our first VHS video recorder because this one has the fancy new fangled remote control, complete with cord connection!

The home video market really took off when VHS and Betamax machines came down in price sufficiently for families to consider buying them. A kind friend invited Simon and me to her home to watch The Key to Time season on video, recorded off air in 1978: aged 13, we binged 10 episodes a day and were in heaven. British families often rented expensive electronic equipment at the time, rather than buying it, which gave them the advantage of free servicing and upgrades. Simon and I clubbed our savings together to buy a Ferguson Videostar in 1981: it cost £400, which was hugely expensive. It was a mechanical beast sans remote control; when you pressed the eject button, the top sprang open with the noise and force of an ejector seat, and you had to press the play and record buttons simultaneously (a la the contemporary sound cassette recorder) if you wanted to record anything. How we cursed when the Ferguson electronic video recorder – complete with remote control! – came out a few months later. This boasted a long play feature which meant you could get 14, not seven, episodes onto a three-hour tape. And tapes were not cheap: about £10 each in 1980, which was a lot of money for two sixth formers who also had to buy beer and cigarettes.

But we bought the Videostar when we started A levels, mindful of the fact that we would soon be going away to college and might be wasting our time in freshers’ discos when we could be watching Doctor Who instead. We bought it in time to tape The Five Faces of Doctor Who at the end of 1981 and I still have the recordings. These were repeats sanctioned by John Nathan-Turner at the end of Tom Baker’s seven-year reign as the Doctor, stripped across the week in the early evening on BBC 2. The rationale was to remind viewers that there had been other Doctors than Tom and to get them used to the idea of a new Doctor, to be played by Peter Davison, who had just sat up at the end of Logopolis. JN-T won praise, love, and applause from fans for arranging the repeat season which, I am sure I don’t need to remind you, consisted of: An Unearthly Child (the whole story, not just Part One); The Krotons; Carnival of Monsters; The Three Doctors; and Logopolis – the latter containing Tom Baker and Peter Davison and taking the number of featured Doctors to five. Logopolis was considerably less exciting than the other stories as we’d seen it recently on BBC1, so it had the feel of a summer repeat – albeit, one held over to the end of the year. It was welcome to us but not to Frazer Hines, who exclaimed, “Oh, not The Krotons!” when told of the choice of Troughton repeat at that year’s Panopticon. Frazer explained that he, Troughton, and Wendy Padbury had all disliked it heartily at the time and, inevitably, called the monsters The Croutons, but it was the only complete Troughton four parter in the archives at the time and so The Krotons it had to be. (Mindful of releasing the stories on commercial VHS, BBC Enterprises would soon start to invite TV stations across the world to return the old Doctor Who episodes which littered their vaults. But that was not yet.) The first new episode of Doctor Who which Simon and I were to record off air was Castrovalva in January 1982.

Owners of the new Betamax and VHS machines immediately twigged that you could hook two machines together to make a copy of a tape, and a huge and thriving industry of international swapsies of Doctor Who stories began. Australian TV stations were still showing the Jon Pertwee and Tom Baker stories at the start of the 1980s and copies winged their way across the water. Of course, every time you made a copy, there was a fall-out in quality; even taping an episode directly off air led to a noticeable reduction in picture and colour quality. (I remember watching a first generation Betamax copy of Logopolis and was quite dismayed by how the colour bled from the frame of the actors’ faces. How evolutionarily right and proper it was that VHS kicked out that inferior Betamax system!) Once you got to seventh or eighth generation, the picture was distinctly ropey and the sound farted as much as the cassette recordings we had made years before. There were some distinctly rubbishy copies doing the rounds. Single episodes of The Daleks and The Edge of Destruction were knocking about, looking as though they’d been copied 40 times with a picture quality far worse than early silent films. Some of the episodes were of strange provenance: The Edge of Destruction was available to the discerning fan dubbed into Arabic or redubbed into English, presumably from someone’s private audio recording. The lip synching was wildly out, as it was on The Daleks episode one. Even I, a fan as dedicated to the programme as a medieval knight to his lady in a courtly romance, found sitting through 25 minutes, eyes streaming and straining, pretty hard going.

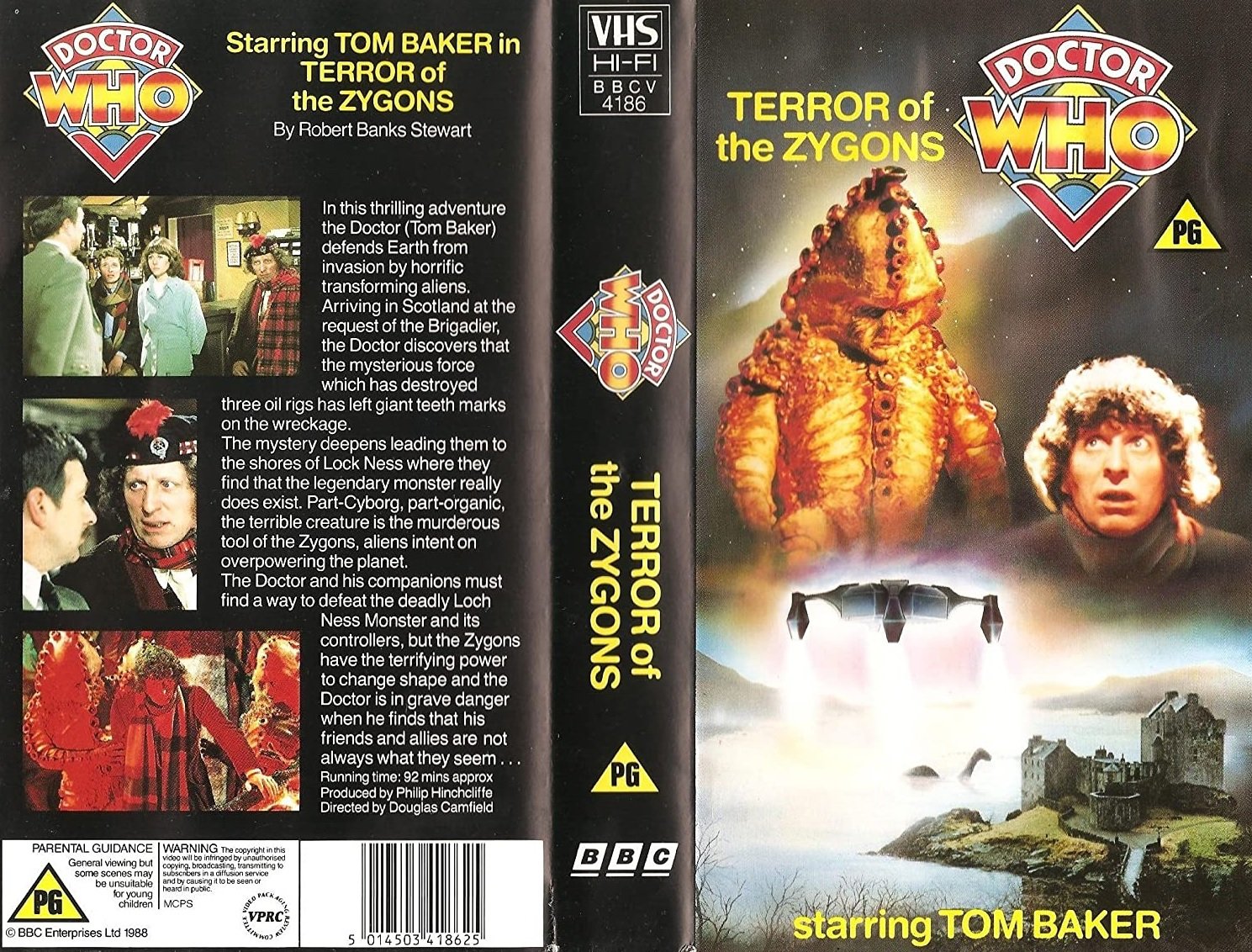

We all experimented with recordings. If you cut out the title sequences from the end of Part One to the beginning of Part Three, you could fit two four-part stories onto a three hour tape. So what if the picture jumped at the edit with a little SQUEAL and green lines snaked down the screen for the next two minutes? Purists would get wise to the merchandise being offered them. “Right,” said a mate at the end of negotiating a deal with me – “so this is your Invisible Enemy and The Sunmakers in exchange for my Terror of the Zygons and Horror of Fang Rock?” “Exactly so,” I agreed. “The episodes to be complete and not edited or adulterated in any form?” he pressed. “Ah, no, we clipped out the title sequences to fit them onto the tape.” “Then,” my contact growled from his bunker in deepest Somerset, “it’s NO DEAL, my friend,” and crashed down the phone.

Some Pertwee and Baker episodes had slipped off the repertoire of Australian repeats, so some stories were sourced from the United States. Australia had the same TV system as the UK, so direct swaps of videos were possible: Simon and I sent copies of Castrovalva to an Australian pen friend who hadn’t seen the Peter Davison stories yet. It wasn’t to be for the USA, whose television system used 525 lines rather than our 625 lines, so the systems weren’t compatible. Enter the Camera Copy. An American video recorder would play an American off-air recording onto an American TV: there to capture the action was a British video camera recording onto a British video recorder. And if you think that would give you a ropey quality copy, you’d be right. I remember watching a camera copy of Terror of the Autons back in 1981, when what I recall most vividly was the rounded edges of the American TV set at the extremes of my picture. Finding my attention wandering, I tried to puzzle out the reflection of the American living room in the said TV’s screen.

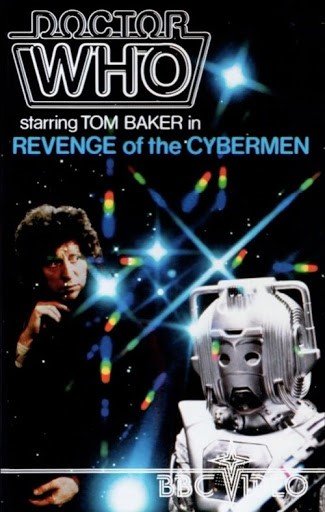

So that was the thriving world of swapsies and cassettes, third generation and 12th generation recordings. It was a happy time of excitement and delirious joy, when you suddenly could see a story you dimly remembered because you had last seen it as a tiny tot, and you built up your video collection, episode by episode. It was also a great way to meet girls, as ladies you had never met smiled at you in the school corridor and said, “You’re Frank, aren’t you? Elizabeth said you had a copy of The Green Death on video. I’d love to see that again, I haven’t seen it since I was little, gosh you’re so sweet.” (Maybe my memory is a bit hazy on the details here.) The commercial and professional world had to come nosing into the amateur scene, of course, and BBC Enterprises asked fans at the 20th anniversary Longleat celebration which story they’d most like to see released on home video. Ho ho, said the fans, writing The Tomb of the Cybermen on their forms: a story which was missing without trace in 1983 and enjoyed a reputation (deserved) as one of the greatest of Who adventures. BBC Enterprises responded by issuing a story which they thought was as close as possible to the fan choice because it only had one different word in its title: Revenge of the Cybermen. Be careful what you wish for, we thought, as we eyed the cassette in video rental shops and WH Smith: the cover featured the wrong Cybermen, from the recently transmitted Earthshock, and the stars from the contemporary titles sequence.

In accordance with the received wisdom that people didn’t want to sit through episode titles, the BBC removed all except the opening titles of episode one and the closing titles of episode four: thus we had the usual effect of Doctor Who edited into movie format, when things build to a climax every 22 minutes and then relax quickly. BBC Enterprises speedily followed Revenge of the Cybermen with a genius one hour, edited version of The Brain of Morbius, perhaps thinking that fans wouldn’t want to sit through a whole 90 minutes. We all scorned and avoided it. The first commercial VHS that Simon and I bought was The Seeds of Death, again edited into a movie and priced at the ludicrous figure of £40 or so: this practically bankrupted us and left us beerless for weeks. Fortunately, our local video rental shop started to stock some of the new releases and we were overjoyed to see Day of the Daleks again. (Note: you could rent video tapes from shops for a small fee and some public, free libraries stocked them too. But where is Blockbuster video now? Swept away by streaming, that’s where.)

It is wonderful to have almost every episode of the classic series available to us for a few pounds a month, courtesy of Britbox in the UK, or for rather more pounds per DVD. But I remember the excitement and joy of being young: when a new story plopped through the letter box in a jiffy bag; when you built up your collection slowly and when you met with the geezer in the pub who would slip you Doctor Who and the Silurians in a brown paper bag if you saw him right with The Time Monster and then slip away into the night.