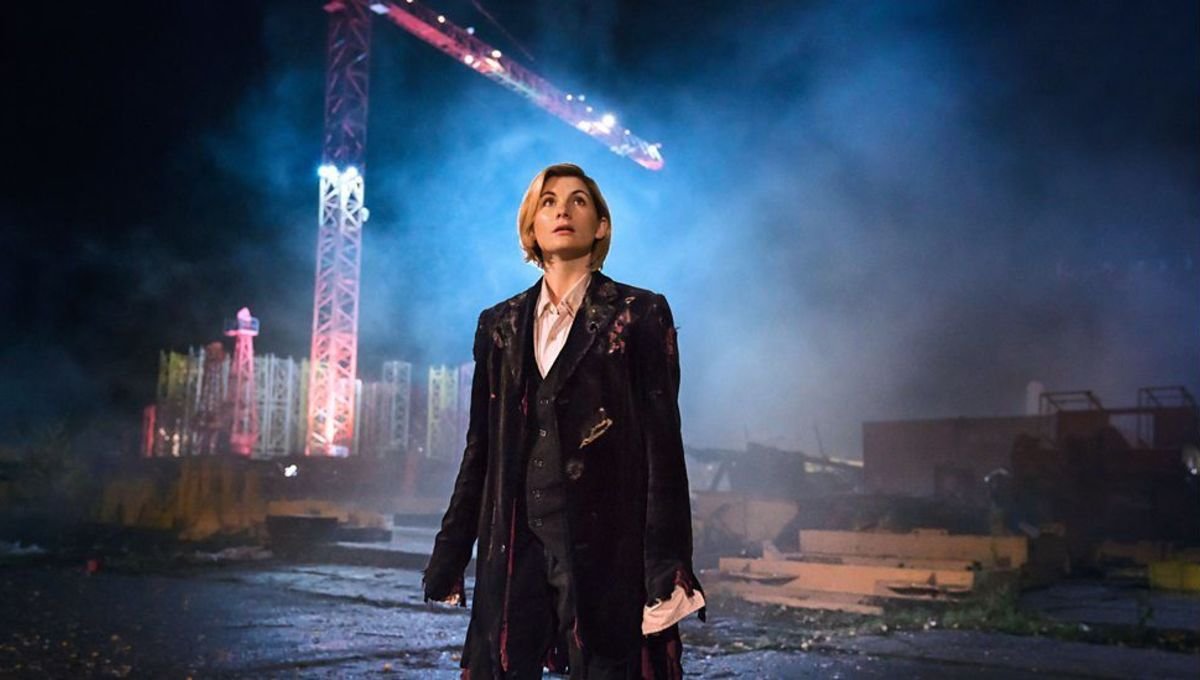

They say you should never open with a flashback, but I want to reverse the hourglass until it lands in October, the year before last. There’s a woman balancing on top of a crane: one of two women who will fall to Earth during this episode, and the only one who will manage to get up again afterwards. Having spent the best part of an hour dallying around the question of identity, she seems to have reached a moment of self-realisation, as we are about to find out when she faces off against an alien Predator (capital deliberate) whose facial piercings border on the comical. “Bit of adrenaline, dash of outrage, and a hint of panic knitted my brain back together,” she says. “I know exactly who I am. I’m the Doctor.”

And across the country, millions of voices cried in unison “Meh, well, okay, kind of.”

I’m racking my brains and trying to recollect whether the fandom was this divided over Capaldi. Of course he has his critics. My mother was one of them (“He’s too old!”, she said over her knitting needles when he sneezed his way into the TARDIS at the end of Time of the Doctor); there are others for whom the show effectively ended with Tennant, or who won’t even touch anything after McCoy. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the culture we live in, where the internet has become a transparent facade, a gargantuan glass frontage through which we can survey all manner of ugliness. It’s a depressing state of affairs that puts one in mind, somewhat bizarrely, of the house in Roald Dahl’s The Twits: a gloomy high-walled cuboid that looks “more like a prison”, but in which the absence of windows is probably a blessing.

So when Whittaker showed up, the cameras were out and the ballpoints were poised, her every move and feint and deleted line all up for scrutiny. What would she be like, this new take on an old idea, this fresh pair of eyes? Would she rise to the challenge or sink like a stone? No one knew, but the one certainty in this brave new world (that’s not a figure of speech) was an unending barrage of superficial reflection and introspection and commentary, mostly from fans with nothing interesting to say, and fuelled by an entertainment press all too keen to turn Tweets and Facebook comments into 300-word pieces of clickbait fluff. I admit that I contributed to this barrage of toxic ephemera, and it is a world I am glad I no longer inhabit.

Was it any good, though? Yes, it was. No, it wasn’t. Have things improved? Yes. No. Is the current Doctor doing a good job? Has her character developed? Yes. No. Perhaps it doesn’t matter; perhaps it does. There is no way to provide an objective, empirical answer; perhaps there never has been. Perhaps that means we have to keep trying; perhaps it means we should stop. No one knows, but somewhere in his grave, Roland Barthes is chuckling.

Say what you will about Series 11 – a very great many have – but it is at least sufficiently emboldened to become its own self-contained entity, to an extent arguably not seen since 2005. It is a series you can pick up and follow (I mean properly follow) with no prior knowledge of Doctor Who. You couldn’t say that for Tennant, or Smith, or Capaldi. This is as coherent and stable a jumping on point as it’s possible to have for a show that is rapidly sinking under the millstone of its own history. You might argue (and again, a very great many have) that the net result of this is a show that wasn’t really Doctor Who, at least not in any recognisable form. I wouldn’t necessarily argue back.

But it’s a marked contrast to the full-on Rise of Skywalker hatchet job that Series 12 is in danger of becoming – where every fresh reference feels like fan service, and where the result is a show that is trying to please everyone at once and is thus in serious danger of failure. And caught in the middle is poor Jodie Whittaker, the sounding board for BBC virtue signalling, trying to embody a character with six decades of televised backstory while keeping it fresh. What was the moment the casting of the Doctor became such a poisoned chalice? Was it when Chibnall signed the contract? Or has this been on the horizon for a while, the sort of slow burn you only see in David Lynch films?

There are many for whom Whittaker became the Doctor the moment she lifted back that hood, a steampunk Scottish Widows commercial (on the BBC!) delivered over new age ambience. There are others who felt it at the aforementioned moment she recalled her own identity; for others it was the moment she welded the screwdriver. Others look to the closing scenes of The Ghost Monument, perhaps when the custard cream drops out of the biscuit dispenser. For a few, it was the appearance of the tuxedo (followed by pangs of regret when she abandoned it the week after). Some felt the writing in Series 12 has upped the ante considerably. Some are still waiting.

Still, certain boxes are ticked. There was a deep-rooted concern that Whittaker would become a sexual, overly competent incarnation; someone who drives the TARDIS perfectly, who has all the answers. That’s generally the way they write women, at least in this day and age. If anything, the reverse is true: she blunders out of a Sheffield charity shop in an ensemble that would make even Mork from Orson raise an eyebrow (“Why can’t she wear a dress or something?” you could hear the Twittersphere grumble) and then proceeds to get lost, break things, and fail to understand the nuances of human communication. She is socially awkward (yes, I know what you’re thinking about, and we’re getting to that) and she makes mistakes, some of them borderline catastrophic. She may not always be the most competent of Doctors, but a Doctor she categorically is, whether you like her or not.

The standard counter-argument to this – one I anticipate in several quarters – is “Well, yes, but she doesn’t embody the Doctor for me, and here are a dozen examples as to why”. Which is all very well, but we might say this about any of them. Yesterday I had someone tell me that Doctor Ruth could not possibly be a new incarnation because “The Doctor is a cross between Sherlock Holmes and Harpo Marx. Also, in Ayruvedic terms, we could say that the Doctor is Vata – with maybe a pinch of Pitta. This person is super Kapha – and she has utterly no Harpo in her and barely any Holmes on display.”

We will forego any snide comments on the brazen pretentiousness of this literary pseudo-intellectualism (it didn’t stop there, but I will spare you the rest) but I’ll grant him this: it does apply, I suppose, to at least a few of the Doctors. Just not all of them. It doesn’t apply to Eccleston. And yet if you’re in a group scenario and you tell people that you could never really believe in Eccleston as the Doctor, you get your head bitten off. Eccleston is the Man Who Resurrected Doctor Who, in the same sense that Sydney Newman is the Man Responsible For Its Creation (in other words, neither statement is really true, but we’re not supposed to talk about it). The Dark World is fair game, but when it comes to 2005, he’s more or less untouchable.

Could it not be that we bring our own baggage to these particular scenarios? Because I have watched Jodie Whittaker grow into the role these past years and I have found myself liking her, even if I don’t always approve of things she’s given to say. There is clowning and there is buffoonery and some of it is gratuitous and unneeded; she spends most of The Witchfinders either getting soaked or tied up. On the other hand, she saves the life of an astronaut with a daring manoeuvre, milliseconds before his inevitable destruction. It is churlish to single out this particular Doctor simply because our memories filter out some of the silliness. Matt Smith faced down the Atraxi on a hospital roof, but he ordered tea in a wild west saloon and waved a Jammie Dodger at a conglomeration of Power Rangers Daleks. There’s no easy way to say this, but sometimes he was cr*p.

To what extent is character defined exclusively by writing, and how much of it is simply a matter of nuance? For example, there are many criticisms levelled at certain managerial decisions taken by the Doctor over the course of Series 11 – that she was cruel to abandon the spiders to their fate, cowardly to allow Tim Shaw to live when he was destined to wipe out another planet, and both cruel and cowardly to eject the P’ting into deep space, for example, where it could presumably prey off other ships. All arguments have their defendants – at the risk of resorting to stereotypes, most of them seem to be white, male, and graced with an inordinate level of testosterone – but it is rather like saying that Pertwee wasn’t the Doctor because he was openly violent and shot an Ogron in the back. (That’s a scene I personally love, because, ill-conceived as it might have been, it’s a perennial thorn in the sides of anyone who claims the Doctor is a gun-loathing pacifist.)

But there are ways and means. Harrison Ford sabotaged his Blade Runner voiceover in the vain hope that Warner Bros. wouldn’t use it; closer to home, Kenny McBain managed to turn The Horns of Nimon into a comedy, for better or worse. Sometimes it’s an accident, but sometimes it’s entirely deliberate. Nicola Bryant, for example, has spoken of how she would work with Colin Baker to establish a less pompous, more positive relationship during her final two stories (The Mysterious Planet and Mindwarp), which simply meant injecting some compassion – an ironic grin, a pause, and a chuckle – into the dialogue. The scenes that result don’t entirely eradicate Baker’s arrogance, but they bring it into line, and there is a warmth to those episodes that Season 22 generally lacked.

Thus it is with Whittaker, with certain exceptions. Let’s establish something: the Doctor’s treatment of Graham at the end of Can You Hear Me? was outwardly callous, initially jarring, and apparently upsetting to a significant (or at least significantly vocal) number of people, to the extent that the BBC had to issue a press statement to exercise some damage control. I have my own views on the matter, and by and large you do not get to hear them. Is it possible that we might have reacted differently had this measure of indifference been displayed by, say, Capaldi’s Doctor? Yes, it is. Is it possible that gender plays a role in this and that, on some level, we expect Whittaker’s Doctor to be more caring because she’s a woman? I suppose it is, but I’m not saying that. Nor am I saying that Paramount deliberately commissioned a dreadful version of Sonic the Hedgehog so they could say that the one they’d been planning all along was the result of audience feedback. Fill in the blanks yourselves.

We might argue, if anything, that Whittaker’s behaviour in this scene isn’t particularly outlandish – at least when you consider the Doctor’s personal history – but that it’s simply outlandish for her. Because when it comes to past form it simply doesn’t fit the mould. This is an incarnation who seemingly thrives on company: who chases after her companions like a dog, leaving anxious phone messages in the manner of a needy girlfriend when they don’t show up; who lingers outside the TARDIS waiting for someone to ask her to tea; and who, when momentarily abandoned at Tranquility Spa, looks alone and bereft and utterly lost.

On the other hand, having her suddenly do something awful and unpredictable is very Doctor. To be specific it’s very Classic Doctor, where the road of so-called character development was bestrewn with ruts and ridges and wreckage. I am forever quoting him, but he was utterly correct – “History,” said Terrance Dicks, more than once, “is what you can remember”, and there are a great many instances throughout the show’s troubled history when the Doctor behaves solely at the behest of that week’s writer, rather than in a way we might call ‘Doctorish’. We have justified these moments; we have explained them away and embellished them and reinterpreted them all in a desperate attempt to tie together some loosely knitted scarf of continuity (crafted in red, green, chestnut, purple, and grey), and called it The Rules, and we expect all writers, seasoned or callow, to adhere to them.

If anything, the problem is that TV has changed: this is an age where avid rewatching and fervent dissection is not only encouraged but more or less compulsory, one of those hidden clauses in a lengthy list of terms and conditions you supposedly agree to when you become a fan. The past need no longer be another country, viewed through the binoculars of Target novelisations or Blue Peter clips; it is there, at the touch of a button, ready to prove you right and everyone else wrong. Why should history be solely what you remember when the archiving is so good? (And yes, I know there are vast chunks missing, but we won’t go there.)

The tedious vaguery that is ‘bad writing’ aside, perhaps the biggest criticism of Whittaker’s first run of adventures was that she simply wasn’t dark enough. There is some truth to this: the Thirteenth Doctor’s inaugural stories were laced with an almost manic-depressive zaniness that betrayed some of the serious issues they tackled. Even when facing down a Dalek, she lacked any real sense of menace, delivering overwrought ultimatums across a control room before craving reassurance that she’d given enough warning. Ultimately she was able to bring it down through the simple virtue of being short. It’s a far cry from Christopher Eccleston, hefting a BBC prop like an angry, frightened teenager, yelling at Nicholas Briggs’ avatar.

That seems, gradually, to be changing. It is a slow and gentle change, and it is tempered by an over-reliance on Mary Sue moments (which usually take the form of impassioned lectures about plastic), but it is a step in the right direction, even if much of the shifting tone consists of the Doctor sitting brooding over the TARDIS console. She may have judo-thrown the Master in the series finale, but Whittaker’s outburst about flat team structure aside there is little sign of the darkness that categorised, say, late Tennant – nonetheless that needn’t be a bad thing. The Waters of Mars is an absolutely terrible story. We’re nowhere near the Time Lord Victorious, but quite honestly, why would we want to be?

The problem is that said tone is inconsistent. The TARDIS interior is a reasonable visual match for the one used by the Shalka Doctor – at least when it comes to lighting – but it doesn’t have the Doctor to go with it. Segun Akinola’s rearranged opening theme is ominous and menacing, teasing that something wicked this way comes, but it’s hard to take it seriously when instead of Macbeth crossing the blasted heath we get the Doctor bobbing for apples. Is it not so much a question of unfulfilled darkness, perhaps, as it is an unreasonable expectation of darkness? And if it is this – if we expect darkness that is not provided – then how much of this is down to the way that episodes are publicised and presented?

Do they even have tone meetings anymore? Because I’m starting to wonder. It is this issue that dogged Star Trek Beyond – a film that was far better than its initial action-driven, Beastie Boys scored teaser would have had us believe. Doctor Who is a family show that doesn’t want to be seen as a family show saddled with a cast who are trying to appeal to every demographic at once and are thus not really appealing to anyone, at least to any great extent, on a regular basis. It is lukewarm television; the very worst of Moffat, repackaged for Generation Z.

And yet there she is, at the centre of things: Jodie Whittaker, the bearer of the poisoned chalice. The woman who is berated for not being a fan; the woman who is routinely described as a ‘man hater’; a woman who gets all the flak for the dialogue she’s given; a woman who is often asked to put a salad garnish on a dog’s breakfast. A woman who has dealt with an inordinate amount of abuse with grace and serenity; a woman who has the good sense to avoid her fiercest critics. But most of all, a woman who injects the Doctor with warmth and personality, even when the stories give her scant room.

I’ve still not convinced you, have I? That’s okay. I think I’m still trying to convince myself.