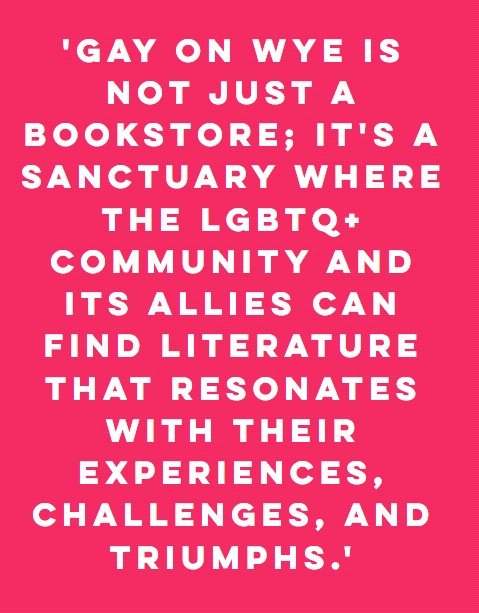

Last holiday, we took a day trip to Hay on Wye on the Welsh/English border, a tiny town with an enormous reputation. Every year, Hay on Wye holds a huge literary festival, and every other shop is a bookshop.* Some new, some second hand and antiquarian, some general, some specialist. As Godchild is trans, we asked in a poetry shop if there was one that specialised in all things LGBTQ+. We were directed a short distance up the next road to a proudly PINK fronted bookshop, with a wonderful owner Thomas Owen who opened it just a few weeks before, and was doing a roaring trade, making people of all ages very happy. This sanctuary for literary-minded minorities is called…?

Gay on Wye.

Of course it is.

As ecstatic Godchild snaffled a bagful of treasures, I considered buying Miriam Margoyles’ autobiography, saying to the owner that I wouldn’t normally but she was about to be in Doctor Who. ‘Oh!’ he said, ‘in that case, you might want…’ and disappeared into the back. He returned with a brightly covered hardback and told me it wasn’t out on the shelves yet, but would I be interested?

I was. I am not gay, or trans, or any label that people wage culture wars over, but people I love are, so I want to learn more.

It’s Emily Garside’s Gay Aliens and Queer Folk: How Russell T Davies Changed TV.

I have seen very little of Russell T Davies’ work (apart from Who, obviously!), partly because I’m not his target audience, but mostly because I don’t watch telly much, preferring audio and books. Garside’s book is academic and far from superficial, a book belied by its colourful, easy-going, and friendly cover. I would describe it an eye-opener more than a page-turner.

I learnt about the gay scene behind Queer as Folk, the loss to Aids of a generation of mentors behind that series and the later It’s a Sin, and the TV production scene behind most of RTD’s career. Written very much from a queer-friendly point of view (Garside describes herself as a massive Who fan, and a queer, ‘Cardiff-based, Welsh nerd’), I learnt terms and ideas that expand my understanding of the complex and varied experience of a growing percentage of humanity. The book is, at times, dense and repetitive; as though the author couldn’t decide which chapter to put a certain idea in, so put it in two or three. I was annoyed by her verbal tic, ‘lean into’, which cropped up far too often. She could have done with a more rigorous editor. But if you want to understand where Rusty is coming from, rather than join one side shouting at the other, this is a very helpful guide. It made me more sympathetic to his purpose-driven work. He is regularly on the media promoting it, or commenting on queer issues, but Garside picks her quotes carefully, showing depth behind the fun or hype.

Garside explains how RTD’s work opened up new spaces for queer stories to enter our living rooms, which made a lot of people feel understood at last – and made others uncomfortable. He’s ‘not afraid to cover things nobody wanted to talk about.’ He’s not perfect and can’t cover all bases, she says, but ‘we cannot expect one writer to fix all our queer TV problems.’ She shares a pivotal point when RTD was basically told by producer Catriona Mackenzie, ‘Go Gay or Go Home.’ Bring out your lived experience as it makes better drama. All good writers write from experience, and his taught him that to be gay was to be political — rebellious even. This was long before any of the awards that gave him confidence, let alone security, yet he went for uncompromising authenticity. You get the sense that Rusty was the right person in the right place at the right time; for example, early Channel 4’s boundary-pushing brief being the exact right time for Queer as Folk. In this series, his characters are archetypes but later works gave a more complex and realistic range of people who happened to be gay. In Bob and Rose, which shows a fluidity ahead of its time, Garside suggests neither gay nor straight people knew what to do with it – ‘a normal gay man was as subversive as a rimming scene.’ There are some interesting angles on the ‘gay actors for gay roles’ debate. In Torchwood, he broke new ground for a pro-sexuality audience, but in Henry (Cucumber), RTD represents the fact that some gay men have a restrained attitude to sex, but feel pressurised into some things they don’t enjoy. He respects his characters and wants to normalise their inclusion in TV’s portrayal of human experience. Garside explores his motivation that the battle for rights and freedoms and safety is never won – things can become dangerous again so easily, as Years and Years warns, and why It’s a Sin spent time on history so we learn from it. ‘TV has power, and RTD used that power to connect people… in a community that lost so many elders, he became an elder by proxy through the stories he told.’

As Garside was writing, RTD had just cast Yasmin Finney, so she opens the debate about trans representation, calling for someone – not necessarily RTD – to do for the trans community what he did for the gay community 25 years ago. Godchild (age 21) adds:

“I think, generally, that Garside makes great points as to how RTD – even today – alone makes up quite the proportion of queer representation in British media, especially one that isn’t so stereotypically driven. I agree with Garside that, yes, it is flawed or dated but it is still some of the better representation because there simply isn’t that much of it, and what there is is not really written for the queer audience (I recommend this video as an example, which discussed how sapphic representation is done for the male gaze as it is the majority of the audience, and therefore is catered to them for, at the very least, economic reasons and likely due to other factors like engrained misogyny). I think Garside could have emphasized more on the still-present need for a huge improvement in queer representation as a whole.

“The open celebration and representation of being queer isn’t in itself an ‘agenda’ but supplying a very starved audience with characters that at the very least tolerate and maybe even accept people who are like that queer audience in some way, and showcasing to the non-queer majority that the queer minority exists and doesn’t want to be hushed up like something that’s shameful. Queer visibility, representation, and tolerance is inherently ‘political’ because society and politics are not inherently made to be queer-friendly or protective of queer identities – as RTD says it something that has to be challenged time and time again.”

But it’s not all about being gay. Garside explores RTD’s signature style with pop music and character-driven story very well. She celebrates his joy at kids’ recognition –‘it is playing a game with the country and it’s wonderful.’ His relationship with the media is explored too, both in his use of it (we all know Trinity Wells!), and its use of him for scandal that sells. RTD ‘often looks at how the media influences and controls people.’ Years and Years is ‘an indictment of all who consume media propaganda.’ Garside goes into some detail on how ‘Davies has never shied away from politics’ – who knew? Describing Vivienne Rook (Years and Years) as ‘a more competent Nigel Farage’ might irk some readers! I enjoyed the chapter on the Thorpe scandal – media, politics, and queer history – and the candour of showing that not everyone involved was happy with RTD’s interpretation. Class too makes for a good chapter, as RTD broke the EM Forster or Philadelphia mould of upper-class ‘nice’ gays, for a man whose Mum filled envelopes to earn rent. There’s a lot of recent socio-political history to mull over in RTD’s oeuvre.

Garside may be mostly a fan of RTD as well as Who, but is not universally gushing; for instance, she discusses how Torchwood seemed to break the ‘bury your gays’ rule when Captain Jack wouldn’t stay buried, but that Ianto’s death was unnecessary and unjustified. She even admits that there may be lines crossed in audiences’ and TV makers’ fetishisation of over-sexual content. But it is the human focus of his work that she keeps coming back to. If you are interested in strong women, or nerds before the geeks inherited the earth, there’s lots to chew on — how RTD never represents them as jokes or stereotypes, but real people. He claims the Doctor as chief nerd, who chose to roam all time and space to collect Knowledge. She draws attention to the similarities between the Doctor’s experience and that of many young queer folk being rejected from their home society and having to find a ‘chosen family’ elsewhere, from other misfits and wanderers.

Her thesis suffers from the common tendency of colonisation – claiming all of Who history as a safe space for the queer cause, which might amuse fans of William Hartnell! But she’s right that theatre, TV, and especially sci-fi have always been a safer space for the ‘Other’ in society. And she does acknowledge that just because people find their experience represented in RTD’s work, it doesn’t mean it was purposely written that way.

Garside’s book hints at a RTD legacy, not just the normalisation of ordinary gay experience, but new life he brought to his beloved Wales with more than just Doctor Who, and the elevation of ‘disposable’ entertainment to raise difficult issues. Garside admits some of RTD’s work is dated, but we’ve moved from Captain Jack being scandalous to Heartstopper being mainstream Young Adult fare – partly as a result of what RTD put out there more than a generation ago. But he didn’t just change TV: there’s a telling example of his influence on real life where a 15 year old came out at school after watching RTD’s work, was beaten up badly, which resulted in some of the teachers coming out too in his defence, and having the school policy changed to be anti-homophobic. RTD says he genuinely doesn’t know whether those positives outweigh the negatives.

Russell T Davies is a respected and powerful figure in the TV world. Amongst everything else he has fought for and achieved in his career, Garside is thankful he devotes so much time and love into our favourite show. ‘The universe feels a lot less lonely knowing the Doctor is out there. Russell T Davies gave us that back.’

So over to you; is his purpose-driven work a force for good or a millstone round the Doctor’s neck – or both?

*I may have exaggerated slightly.

Gay Aliens and Queer Folk: How Russell T Davies Changed TV is out now.