This review is dedicated to the legacy of Terrance Dicks, 1935-2019.

You took me on so many adventures, but always brought me safely home.

In 1977, a fortress of Saturday night television began to crumble. In 1974, producer Philip Hinchcliffe and script editor Robert Holmes had inherited Doctor Who from a team that, after five years, was creatively and emotionally drained and ready to move on. Fortunately, Barry Letts’ last significant decision as outgoing producer gave the series a shot of adrenaline second only to the debut of the Daleks in Season 1: he cast the unknown Tom Baker as the newly-regenerated Time Lord. Baker’s toweringly charismatic performance, combined with Hinchcliffe and Holmes’ superb scripts and production, heralded three years of a quality and consistency unparalleled in Who’s 11-year history. Classics such as The Ark in Space, Genesis of the Daleks, Pyramids of Mars, The Deadly Assassin, and their valedictory The Talons of Weng-Chiang filled a reservoir of popular affection for the series that has still not drained.

And then, in 1977, the BBC split the team. The Sixth Floor Suits worried that they had bought vigorous drama, critical applause, and a robust viewership at the price of too much darkness, violence, and horror. The crest of their concern came with the minor press outcry over Season 14’s The Deadly Assassin, which led to Director General Sir Charles Curran apologising to Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers and Listeners’ Association and the BBC erasing the serial’s infamous Part Three cliffhanger from the master videotape. Nobody who did not see it on broadcast would ever see it, and all home releases since have used the Part Four reprise.

Robert Holmes would leave during Season 15, while Philip Hinchcliffe was moved to a series thought better suited to his uncompromising style, the gritty police drama, Target. Meanwhile, a new producer – Graham Williams – was brought in from the series he had just finished creating… the gritty police drama, Target. Williams’ brief for Season 15, from outgoing Head of Serials Bill Slater, was simple: less violence, fewer scares, more humour, and come in on budget.

That latter decree should go without saying, but the 1973 OPEC embargo – retaliation against US support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War – had pushed crude oil from $3 to $12 per barrel. This ‘oil shock’ had inflamed inflation throughout Western Europe and America, compelling public sector unions to seeker higher wages to mitigate their workers’ hardship. This was a double bind for the BBC: both rapidly rising prices – quotes for scenery and props would expire within weeks – and a heftier payroll. So, Williams found himself trying to make his debut on one of the highest profile and most technically demanding programmes on TV while tightening purse strings strangled his production and strikes bit precious days out of his schedule.

One early decision would haunt both Williams and the series for years. While Tom Baker was not in charge, he was, to borrow a phrase, ‘full of ideas’. Under Hinchcliffe’s tight rein, his more outlandish suggestions were diplomatically declined. But Williams loosened the leash, reasoning that Baker was the show’s principal asset and could be relied upon to inject more of his humour and eccentricity into the role. By the end of Season 15, Baker was rewriting scripts on set and (in Underworld) even conceiving and directing his own scenes. The bottle uncapped, the genie would only become more strident as the years progressed, giving a more flamboyant and mercurial performance, demanding script and casting approval, and openly deriding writers and directors. Baker and Williams’ relationship would crumble to the point where both would threaten to leave if the other wasn’t sacked. It would take John Nathan-Turner to finally bring Baker back under control, via the handy expedient of accepting one of his many resignation threats – ironically ensuring that his final season would be one of his finest. Season 15 is the transition between Baker’s earlier, more restrained characterisation and the broader, more knowingly eccentric performance that would dominate Seasons 16 and 17. It’s worth emphasising here that Baker did not run off the rails unbidden; he was initially encouraged by Williams and BBC executives as a direct response to concerns about the previous season.

Baker’s co-star for the year would be Louise Jameson, reprising her role as Sevateem warrior, Leela, who had joined halfway during the previous year in The Face of Evil. It’s easy to forget the hill Jameson climbed: winning favour with the public while following the hugely loved Elisabeth Sladen and contending with an irascible and unwelcoming leading man. Even when not given the strongest material (and only Leela’s creators, Robert Holmes and Chris Boucher, truly knew how to write her best), Jameson ensures Leela grows with every story. Despite real life tensions, the relationship between the Doctor and Leela, with its Pygmalion overtones of Professor Henry Higgins educating Eliza Doolittle, is a pleasure – not least because Leela’s native cunning so frequently foils the Doctor’s louche savoir faire. It’s a thread each story would pick up until Leela ‘graduated’ (if one can so dignify her departure) in The Invasion of Time. In the opinion of this reviewer, Leela is a classic-era companion of the first rank: secure in the company of Barbara Wright, Jo Grant, Sarah Jane Smith, Romana, and Ace McShane.

Williams also came to his new role with a Big Idea. In a three-page proposal, accepted by Bill Slater, Williams suggested that the Doctor’s universal wanderings lacked moral purpose and so proposed they give him a mission. In so doing, he also suggested an important addition to the programme’s mythology, two titans who would bestride even the god-like Time Lords: The Guardians. It would be the White Guardian who would charge the Doctor to seek out elements of an all-powerful object capable of restoring balance to the cosmos and to ‘beware the Black Guardian’.

But The Key to Time would have to wait until Season 16. Williams was forced to abandon the first script for Season 15 and there simply wasn’t the time to put his idea into practice. That abandoned first script was Terrance Dicks’ The Witch Lords (in later drafts The Vampire Mutations), several years later to become Season 18’s State of Decay. Bill Slater’s successor as Head of Serials, Graeme MacDonald, vetoed the story as he didn’t want anything that might be seen to be mocking their forthcoming, prestige Christmas adaptation of Dracula. Robert Holmes then asked Dicks, the safest pair of hands Who ever had, if he would write a replacement. So, Terrance asked what Bob what he wanted. Bob puffed on his pipe a moment: how about something on a lighthouse?

Horror of Fang Rock

The Horror of Fang Rock was the second story to be filmed but the first broadcast. Terrance Dicks knew little about lighthouses and – so he recounted – he suspected Holmes requested the theme partly in revenge for Dicks having given him an unwelcome medieval brief that eventually became The Time Warrior in 1974. In Dicks’ hastily written replacement, the Doctor and Leela arrive at a lighthouse at the turn of the 20th Century that is about to come under assault by a solitary, shape-shifting scout for the Rutan Empire. The situation is then compounded by the arrival of a yacht-load of aristocrats who bring with them their own schemes and grievances. There then ensues the classic ‘base under siege’ story so popular during the Troughton era.

For a serial now widely thought a classic, it prompted several misgivings. Tom Baker was unimpressed with the script, but by this point that was common. More significantly, director Paddy Russell didn’t think much to the plot or characters. She was also concerned about shooting in a set with as many reflective surfaces as the lamp room and so wanted the number of scenes in it reduced. Russell’s gravest concern was prompted by being forced by the script delay to mount the production at the BBC’s Pebble Mill studios in Birmingham as, by the time Dicks delivered, Television Centre was booked out. One must remember that, although the visual effects in this era now often seem quaint, at the time Doctor Who was probably the most technically complicated drama on any channel, and Russell worried Pebble Mill lacked the requisite skills and facilities. The Pebble Mill staff, on the other hand, were keen to show their mettle and Russell finally agreed, with the proviso that she bring a hand-picked visual effects supervisor with her: Mitch Mitchell. There would also be a three-day shoot at the Ealing Studios for visual effect model sequences.

Fang Rock is a masterclass in Terrance Dicks’ writerly acumen: his economy, his ability to work to a brief, his intimate understanding of budget restraints, and, highest on the list, the command of structure that had made him such a superlative script editor. Part One introduces us to the lighthouse and three generations of keeper: sagacious Reuben, steady Ben, and callow Vince. All three characters are well-drawn and likeable, and Dicks cleverly provides time for the audience to get to know and care about them. This matters because they’re all going to die. Colin Douglas’ Reuben is particularly enjoyable, as is his later performance as the infiltrating Rutan scout impersonating him (which would occasion the most sinister smile in Doctor Who until Dr Judson threw off his wheelchair in The Curse of Fenric). The murder of young Vince, killed by what appears to be his trusted mentor and friend, is more tragic for the carefully established relationship between the two men.

The lighthouse, too, is a character, owing to first rate set design by Paul Allen, who drew inspiration from Lighthouses of England and Wales by Derek Jackson and a visit to Southwold Lighthouse in Suffolk. Excluding the island exterior, shot at Ealing, there are only six sets in the entire production: the lamp room, the generator room, the crew room, the sleeping quarters, and two sections of stairway. The attention to detail impresses, right down to the curved doors. The corridor sets were also technically clever – moveable and hinged in order to allow Russell a wider range of camera angles. The effect is to make the lighthouse believable, convey a sense of confinement, and allow enough variety to maintain visual interest throughout.

Part One also teases the Rutan menace, when Vince sees a ball of light (the Rutan scout ship) appear in the sky. This is easily the weakest visual effect in the production, but it’s not on screen for long. Much more successful, for the time, is the shipwreck at the end of Part One, accomplished with a model left over from The Onedin Line. It mostly works well, but the camera lingers a little too long as it runs aground. The Rutan – a large green jellyfish-like affair — is realised well enough too, although it’s difficult to see how they would have become a recurring villain like the Sontarans unless they spent most of their time in human form.

In Part Two, Dicks introduces the shipwrecked aristocrats: Skipper Harker, Colonel Skinsale, Lord Palmerdale, and Palmerdale’s ‘personal secretary,’ Adelaide Lesage. Skinsale and Palmerdale bring intrigue – Palmerdale’s exploitation of Skinsale’s debts – and a small quantity of diamonds, which will prove crucial later. All four are well-performed, with Skinsale the most engaging. He is a weak, vain man but a relatively decent one. To pull this off requires a deft backgrounding of his inevitable complicity in the horrors of British colonialism without ignoring it entirely:

Adelaide: The girl [Leela] is very strange, too.

Skinsale: I don’t know about strange, but she’s not a bad looker.

Adelaide: Perfectly grotesque, in my view. Were you a long time in India, Colonel?

Skinsale: Long enough, my dear, to learn to appreciate nature.

This may be Dicks but, from the language, one senses Holmes’ hand as well (and from The Sun Makers later in the season, we know colonialism had been very much on his mind). Whoever the author, one can read this as portraying Skinsale as a man whose Victorian racism has been tempered by familiarity with ‘nature’ (however equitable or sordid that familiarity was). Arguably, imperialism also emerges thematically, in that the lighthouse’s occupants are essentially victim to Rutan racial supremacy: the Earth is but a foothold in a wider conflict, and humans are all a Lesser Race.

Lord Palmerdale makes for an enjoyable villain: scheming, avaricious, dismissive of the ‘lower orders,’ and ineffectual once his wealth is nullified. He spends the story trying to sneer, cajole, bully, and bribe his way out of a predicament wholly of his own making, but even in a lighthouse he is out of his depth. One of the serial’s most compelling moments is Vince burning Palmerdale’s bribe: £50 (about £6,100 in 2019 sterling) reduced by circumstance to useless paper. It’s a theme explored later with the diamonds.

Harker is a relatively minor part, but still gets a moment when he stands his ground with Palmerdale. Adelaide is the weakest of the characters — with no role in the story but to be terrified, hysterical, and vituperative — but Annette Woollett does what she can. Certainly, one must admire her commitment: in Part Three, when Leela slaps Adelaide, Woollett asked Louise Jameson to produce real tears with an actual blow. Given how irksome Adelaide is, it’s probably the most crowd-pleasing moment in the serial.

Tom Baker and Louise Jameson are both strong in this story and, notably, it was during this recording that their relationship became less strained. In the scene in Part Three in which the Doctor comes in carrying Palmerdale’s body, Baker repeatedly came in ahead of his cue. Jameson insisted on three retakes, despite feeling pressure to let the matter pass. By standing up for herself, Jameson then won Baker’s respect and his attitude to her softened. This was also a significant story for Jameson in that her request to no longer wear brown contact lenses was honoured. Dicks wrote a coda, whereby the explosion of the Rutan spaceship changes Leela’s eyes to Jameson’s natural blue.

Leela does well in this story with several strong moments. The savage’s affirmation of science in the face of Adelaide’s backward belief in astrology is pleasingly unaffected and her reaction when Reuben declares that the ship is about to hit the rocks – ‘They will all die, then’ – bespeaks the cold pragmatism of the huntress. Baker delivers his key lines with the charismatic authority that defined his early interpretation:

Gentlemen, I’ve got news for you. This lighthouse is under attack, and by morning we might all be dead.

Indeed, such is Baker’s facility for saying the most preposterous things with unflinching, iron conviction, that one wonders why he didn’t follow Doctor Who with a career in Parliament. He also handles the humour with the subtle shading that, regrettably, boredom caused him frequently to abandon in later stories and seasons.

In the remaining two parts, Dicks increases the dread as, one suspects with great satisfaction, he has the unseen Rutan set about polishing off the crew one by one, including in the guise of Reuben. The Doctor eventually mortally wounds the creature with an improvised mortar before utilizing the lighthouse lamp and the largest of Palmerdale’s diamonds to focus a laser beam upon the Rutan mothership. In structural terms, it’s pleasingly neat; grimly so, given it’s the only time in 26 years that the entire guest cast dies.

While Dicks’ strength is structure, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t furnish us with memorable moments as well. When Leela asks the Doctor how he plans to get around the Rutan, he replies, ‘with discretion.’ There’s also the saucy, ‘What the Butler Saw’ style postcards among Reuben’s belongings; comically tame by modern lights but one of only two references to pornography in the entire series (the other being The Eleventh Hour in 2010 – Steven Moffat’s naturally).

Most telling is the economical way in which Dicks despatches Skinsale. The Doctor rummages through Palmerdale’s diamonds, finds the one he needs for his laser, and then tosses the rest on the stairs before making to return to the lamp room. The impecunious Skinsale then falls to his knees to retrieve his salvation. But it’s damnation as the Rutan strikes. In a single moment and with no dialogue, Dicks does two, perhaps three things. Firstly, he kills Skinsale with the character flaw that had enthralled him to Palmerdale in the first place, as he dies grubbing for money. Secondly, Dicks illuminates the Doctor’s moral elevation over venal humans: he sees diamonds not as objects of wealth but as means of survival. It’s a powerful statement made with not a word uttered. Thirdly, one can see the moment as a repudiation of imperialist values, as the gems, very likely robbed from a British colony, prove to be their (symbolic) thief’s undoing as he is murdered by an even greater conqueror.

Despite its troubled gestation, The Horror of Fang Rock is a true classic of the period and another demonstration that Doctor Who can succeed with small, intimate stories. Dicks works the ‘base under siege’ theme through in a thoroughly entertaining way with a strong structure. It may seem pedestrian to stress the value of a story with a beginning, middle, and end, but it’s a lesson that Steven Moffat could have done with during some of the sugar rush exuberance of his time as showrunner. Fang Rock lacks ostentation and bombast, it is not ‘clever’ or pleased with itself, but it is an involving and durable piece of drama: it is by far the most technically accomplished and most interesting serial of the season and a tale only burnished by the passing of the years.

The Invisible Enemy

The Invisible Invader (as originally titled) was the second story to be broadcast but the first to be filmed. It was commissioned from regulars Bob Baker and Dave Martin, ‘the Bristol Boys’ who had previously delivered The Claws of Axos, The Three Doctors, and The Hand of Fear. Unlike Fang Rock, Enemy lays down a clear marker for the era to come.

The Bristol Boys had been inspired by reading about viruses, leading them to think that an intelligent virus might make an interesting Doctor Who villain. Their story has the Doctor infected by an alien parasite (the Swarm), whose invasion through contagion has now reached the Terran solar system. Those infected become drones in the Swarm’s army, confirming their subjection by stating ‘contact has been made’ and sprouting ridiculous eyebrows. Chief among the infected is the supervisor of a refuelling station on the Saturnian moon, Titan (Michael Sheard, in what one might describe as a ‘career Lowe’), where much of the action takes place. The other main location is the Bi-Al Foundation, where the infected Doctor seeks help from Professor Marius (played by Frederick Jaeger). Marius injects miniaturised clones of the Doctor and Leela into the Doctor’s brain to destroy the Nucleus of the Swarm. If the idea seems reminiscent of the classic SF fantasy film Fantastic Voyage (or the ’80s remake, Innerspace), it’s worth bearing in mind Malcolm Hulke’s dictum: all you need for a good Doctor Who story is an original idea – it doesn’t have to be your original idea. This clone gambit goes wrong: the clones expire, the Nucleus escapes via a tear duct and, becoming macroscopic, it causes death on a large scale before the Doctor inevitably blows it up.

It’s generally something of a fool’s errand to seriously critique the ‘science’ of Doctor Who but the ‘Kilbrackan’ cloning technique is risible. The ersatz Doctor and Leela arrive with their progenitors’ clothing and breathe unassisted inside the Doctor’s body. Worse, when ringer Leela kicks something inside the Doctor’s brain the repro-Doctor is pained. Similarly, when the facsimile Leela is attacked by the phagocytes, the ditto Doctor cannot help because they are ‘his own defences.’ The characterisation is also poor, since neither seems remotely concerned that they have about 30 minutes of life. Clone or not, they have their own subjectivity, which ceases when they die. It’s ludicrous, frankly.

But of course, the big star of this story — and its great legacy — is without doubt Professor Marius’s dog-like computer, K9. Decades later, the tin dog remains both controversial and marketable: either a fillip to children’s enthusiasm like nothing since the Daleks or a coffin nail with a waggy tail. Originally named FIDO (Phenomenological Indication Data Observation Unit), K9 was designed by Tony Harding and built by the Radio-Controlled Model Company in Hartington for the purposes of a single appearance. Director Derrick Goodwin cast John Leeson (Rainbow’s original Bungle Bear) as the voice and, when the budget would not allow Nigel Brackley (K9’s RC operator) to attend, he stood in for the dog at rehearsal. Leeson’s physical performance entertained the cast so much, particularly Tom Baker, that he would do it for every subsequent serial. This helped as, notoriously, Baker found the prop tiresome and was not above giving it solid kick across the set.

During filming, Graham Williams toyed with the idea of keeping the dog as a regular and, in fact, two endings were shot. Even this early, however, one could see the problems that would dog K9 throughout its four years on the series. It is cumbersome, short, sometimes too powerful for the story, and defeated by anything more than a gentle incline. It’s written out several times in its first story alone and, when it’s required to enter the TARDIS at the end, the camera must pull discreetly away. The prop’s motor was very loud (at one point in this story, Louise Jamieson must raise her voice to be heard) and the RC interfered with the cameras. For the following stories, K9’s internal workings would be redesigned for more long-term use, but the narrative bugs were harder to fix and so K9 would be frequently forced to stay in the TARDIS or, on one humiliating occasion, contract ‘robot laryngitis’. Fortunately for Doctor Who, K9 descended to his true nadir well outside of the parent series, scraping through a seemingly endless stack of barrel bottoms to end up down under. John Nathan-Turner would repeat the mistake a few years later with Kamelion.

One of the defects of Enemy, and indeed of the whole Williams era, is that its legs frequently can’t follow where its eyes want to lead. Baker and Martin’s script has commendable ambition (if little thematic depth aside from the comparison of humans with viruses), but they seem naïve as to what could be realised convincingly within the series’ budget and resources, especially in the ’70s economy. Philip Hinchcliffe was always more conservative in this respect, but Enemy does not show similar caution, with embarrassing results when the arch foe transmogrifies into a four-foot cling-filmed space prawn that looks like it has shuffled out of the Blue Peter studio. With lower lighting and forgiving camera angles, it might have appeared less risible (certainly, the shadowy Titan scenes work better) but under Blankety Blank-level glare, it’s absurd. John Scott Martin – the series’ longest-serving Dalek operator – must have been grateful to be unrecognisable.

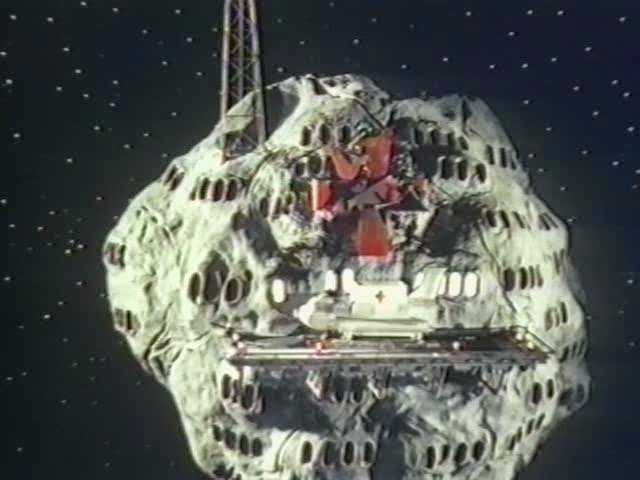

Easily the most egregious ‘special’ effect sequence in the whole production, though, is when K9 supposedly blows a chunk out of a corridor wall. On the first take, the sequence looked much better: the breakaway section of wall was suitably disguised and blew out on cue, complete with a smattering of rubble, but for some reason the take was not satisfactory. The shot had to be remounted with only minutes before the mandatory 10pm shutdown, so the wall section was hastily pushed back into place, but the seams left clearly visible. Unforgivably, the mock rubble was still left on the floor. We might fairly attribute much of the story’s visual weakness to Derrick Goodwin’s inexperience. While he had helmed comedy shows like On the Buses and Thick as Thieves, he’d never tackled a show as technically demanding as Doctor Who. This is not to say that all the effects in Enemy are subpar: far from it. Ian Scoones’ model work for the ships and the Bi-Al Foundation asteroid is exemplary for the period. He, along with a young Matt Irvine, supplied the serial with 61 model shots, all created at the Bray Studios, which were the series’ most sophisticated until that point. Also impressive are some of the chromakey sequences used to depict the inside of the Doctor’s mind. Unfortunately, they’re often intercut with some particularly dreary sets, which suffer badly in such immediate comparison.

The deepest problem with The Invisible Enemy is its shallowness, contrasting sharply with Fang Rock’s focus on character, suspense, and drama. Enemy is merely driven by plot. As a concept, it’s fine, but there is no attempt to populate the drama with realistic or dimensional characters and so it is hard to care what happens. Frederick Jaeger is able to do something with Professor Marius and John Leeson has some fun with the Nucleus (the scene in which he and the Doctor discuss survival of the fittest is a highlight) but the rest are cyphers running down dreary, over-lit corridors. This sadly includes Michael Sheard, a stalwart of several Doctor Who appearances, Admiral Ozzel in The Empire Strikes Back, go-to Hitler, but probably best known for playing an even more reviled villain: Grange Hill’s Maurice Bronson. Sheard’s talent was much better used as the tragic Lawrence Scarman in Season 13’s Pyramids of Mars. Here, he is squandered. A particularly grievous example of poor characterisation is the alacrity with which Professor Marius parts from his ‘best friend and constant companion’ at the end. Even allowing for the indecision at the time as to whether they would retain K9, there’s no excuse for such shoddy writing.

To sum up, there’s much to appeal to less discerning children under eight, but very little to engage the adult viewer (although the ‘Finglish’ phonetic nomenclature is fun) and so little content to review at any length. K9 is the exemplar of this new more superficial approach. Of course, Doctor Who needed to appeal to children, but within the context of it being a family entertainment speaking to different age groups. This richness is absent here and, as such, The Invisible Enemy is the epitome of what too many people would later come to believe all Doctor Who was: a childish, shallow, over-reaching run-around down tacky corridors.

Image of the Fendahl

Image of the Fendahl was the fourth story to be produced but was broadcast after The Invisible Enemy as the production team felt it provided a better contrast than The Sun Makers would have done. It would be the last properly gothic story until State of Decay in Season 18. In a priory just outside Fetchborough, Dr. Fendelman and his team (Max Stael, Thea Ransome, and Adam Colby) are conducting tests on a human skull unearthed in Kenya. Fendelman believes the skull is 12 million years old (far older than it ought to be) and wants to use his time scanner to prove it. Each time they operate the scanner, Ransome appears affected and eventually is transformed into the core of the Fendahl, an ancient creature that may be responsible for the evolution of human life. Meanwhile, the Doctor and Leela, drawn by the time scanner, become embroiled in a battle with Fendelman, a cult of Fendahl worshippers, and the Fendahl itself.

After Enemy, Fendahl feels like the afterglow of the Hinchcliffe and Holmes era (an impression only strengthened by returning to Mick Jagger’s Stargrove Manor in Hampshire, previously used for Pyramids of Mars). Chris Boucher, with the excellent Face of Evil and the even stronger Robots of Death on his C.V., turns in his final script for Who. The result is not quite so polished, but that may be because Robert Holmes was by this point heading out of the BBC car park, to be replaced as script editor by Antony Read. On Holmes’ recommendation, Boucher would move on to great success as the script editor and writer on Blake’s 7, building on Terry Nation’s notoriously ofttimes sketchy scripts and crafting much of the crackling dialogue that was such a key component of that show’s success.

Thematically, the serial has two obvious parents. One is Arthur C. Clarke’s 1951 short story, The Sentinel, in which an alien pyramid is uncovered on the moon, leading its discoverers to speculate that it is an ‘alarm clock,’ alerting its creators to the emergence of our fledgling technological society (the inspiration for Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey). The other is Nigel Neale’s superb Quatermass and the Pit (though apparently less the 1958 BBC original than the 1967 Hammer remake). In fact, one can hear echoes of Professor Bernard Quatermass and his adventures throughout Doctor Who, particularly in the earthbound stories of the Pertwee era, but also in later serials such as The Seeds of Doom, and The Awakening. Indeed, the first episode of Ben Aaronovitch’s Remembrance of the Daleks is a veritable love letter to the third Quatermass, right down to Rachel Jenson’s reference to ‘Bernard’ and the British Rocket Group.

Fendahl’s cast are near uniformly excellent. The marvellous Denis Lill, who watchful viewers will know from long-running roles in Terry Nation’s Survivors and Only Fools and Horses, affects the fruitiest of ‘Cherman aksence’ to play the tragic obsessive Fendelman. Wanda Ventham is engaging if underwritten as Thea Ransome and satisfyingly statuesque as the Fendahl core. Scott Fredericks, who gives an excellent turn in Blake’s 7 Weapon as the ‘psycho-strategist’ Carnell, makes the best of some overwrought lines as Max Stael. Edward Arthur’s Adam Colby is very watchable, if rather too theatrical in his enunciation. He does get one of the show’s finest lines, however, when he labels Jack Tyler a ‘swede-bashing cretin.’

And this brings us to the show’s very snappy double act: Geoffrey Hinsliffe’s Jack and his gran, Martha, played to scene-stealing perfection by Daphne Heard. While Martha gets most of the comedic action of the story, she is far from being mere light relief. Her scene in the kitchen, early on, when she warns the security guard that ‘there isn’t a dog born that as attack me, boy’ is delivered with real authority and establishes her early on, for all her fruitcake and foibles, as a formidably wise woman. Leela’s respect for Mother Tyler is also a nice reminder of her Sevateem tradition of affording elders due status. Jack and his gran make a fine pairing and, but for the sheer weight of years, they surely would have made a Big Finish double act as worthy as Jago and Litefoot.

The two regulars are on good form, with Baker treating the script with the seriousness it deserves. Indeed, it’s largely Baker’s gravitas and palpable dread that really sells the drama. Leela, in the hands of her creators, is particularly well written, too. It’s ironic, then, that it was during this story that Louise Jameson decided to leave the show, having been offered the role of Portia in a production of The Merchant of Venice at the Bristol Old Vic. K9 is absent from the story as Boucher didn’t know about him in time.

This was George Spenton-Foster’s first of two directorial assignments on Who. He’d return for The Ribos Operation the following year and helm several episodes of Blake’s 7. He does a solid job with the story although without the flourishes one would have seen from Paddy Russell or Douglas Camfield. Where Fendahl disappoints is that there isn’t enough plot for four episodes and the resolution is rather limp and the sense of threat limited. For an enemy that is talked up in such hushed tones by the Doctor, the Fendahl core and Fendahleen do very little. Ventham’s physical performance, costume, and make-up are certainly alluring (ironically, she lost out to Shirley Eaton in auditions for Goldfinger) and the painted-on eyes trick is simple but powerful (and would be repeated in The Keeper of Traken). Her transformation (using roll-back and mix) is also impeccable, but none of this quite distracts from the fact that, aside from some swishing of robes, she doesn’t do a lot. The Fendahl core prop is imaginative but very much a poor man’s Triffid (and was initially deemed so phallic as to require hasty modification). Nor can one turn to Stael’s cult for any drama, as they serve no real purpose other than to be Fendahl fodder.

One moment that is noteworthy is Stael’s suicide by gunshot, which is powerful (especially for a family show) and the type of scene the modern series simply would not attempt. Indeed, but for the intervention of Graeme McDonald, it would have been even more disturbing, with Stael seen putting the gun in his mouth. Beyond this, the threat is sold largely through the Doctor’s trepidation and the terror of the other characters. It almost works but not quite. Another problem that would have been solved with another draft is that the Doctor and Leela don’t get into the real action until the beginning of Part Two and the Doctor’s interaction with the scientists is pretty much restricted to the final part. Nor is there much real discussion of the matter at hand between the scientists: their personalities and relationships are depicted quite well but what’s largely missing is proper discussion of the import of their work. Nor, frankly, does the script properly reconcile the notion of the Fendahl tinkering with our evolution with its nature as a destroyer of all life. Had Holmes been fully in residence, this problem would surely have been fixed (and the ever-practical Dicks would have given it short shrift).

In sum, Image of the Fendahl is a thoroughly entertaining serial, although the journey ends up being slightly more satisfying than the destination. It’s an intelligent, imaginative, and eerie reworking of some old themes, though it never quite scales the heights of its illustrious source material. It’s an episode too long and a draft too few compared to where it would have been under the previous management, but it’s still highly enjoyable and atmospheric; in my opinion second only to Horror of Fang Rock this season.

The Sun Makers

The Sun Makers (not the Sunmakers of the Target novelisation) began broadcast on the 26th of November 1977, just three days after the series’ 14th anniversary. While Fang Rock and Image of the Fendahl appear to be holdovers from the Hinchcliffian Age and The Invisible Enemy is unalloyed Williams, the Sun Makers presents as a fusion of the eras. Robert Holmes’ script features his characteristic satire and dark humour, while the production follows the style that would prevail until The Leisure Hive in 1980.

The story is a dystopian satire, following the furrow ploughed by George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, and Franz Kafka’s The Trial. Indeed, the opening shot very much recalls the seminal 1954 Rudolph Cartier adaptation of Orwell’s classic, in which the mighty Peter Cushing played Winston Smith. In this case, however, the enemy of the people is not an implacable state but, prophetically, an alien corporation that controls the ‘megropolises’ of Pluto and has enslaved a forcibly transferred humanity (a theme Russell T. Davies would explore in The Long Game in 2005). These aliens are the eponymous Sun Makers, having created artificial stars around Pluto, although so incidental is this point that one wonders if its use as the title reflects a focus lost from earlier drafts. The plot is standard Doctor Who fare: the Doctor and Leela act as a catalyst for a previously ineffectual resistance, they run down a lot of corridors, there are some capturings, and then the huddled masses rise up (off-screen, naturally) against their owners. It’s a technique the Doctor would eventually hone to such an edge that he and Ace would bring down Helen A in a single night.

The reason the story is somewhat prophetic is that, in the West, it’s the labyrinthine machinations of large scale private capital that arguably threaten democratic aspirations more than the increasingly hollowed-out state (a critique already made of Orwell’s ‘diversion’ by the late Australian academic Alex Carey in his Taking the Risk Out of Democracy). Indeed, even at the time, the BBC’s audience research panel recognised The Sun Makers as an ‘expose of super monopoly capitalism’ rather than a fable about the Soviet bloc. In fact, Holmes’ original story idea was to look backward, to satirize the rapacious European colonialism exemplified by the British East India Company, which used its private army and state-sanctioned writ to terrorise and exploit millions of people in India. But Holmes would then overlay this notion with his own domestic concerns at the time, namely his notorious (among classic Who fans) travails with the British tax authority, the Inland Revenue. Perhaps this change in direction, from political critique to personal grievance, also explains the ambiguity of the finished product. It is can be read as both a left-wing satire of unchecked and homicidal commercial capitalism and as a libertarian critique of ravenous and absurd state bureaucracy. When one knows the history of classic era Doctor Who, it’s hard not to view some modern-day fans’ bridling at the ‘sudden’ appearance of politics with some amusement. One difference, though, is that the 2018 episode Kerblam! never manages to formulate its position quite so clearly as by having someone thrown off a roof.

Among the black humour, Holmes’ characteristic wordplay is much in evidence. The story is set on Pluto, but a short hop from the Greek ‘plutocracy,’ and the Collector is a native of Usurious, but a step from usury. The corridors are named after tax forms (P45, P60) and the Inland Revenue is recast as the ‘Inner Retinue’. The suppressant gas is PCM (per calendar month) and Gather Hade’s personal transport is a Beamer (still common slang for the vehicle of choice of that most reviled of road users). Also fun are Hade’s various salutations to the Collector – ‘your monstrosity’, ‘your enormity,’ and so forth (an echo of Holmes’ script calling for him to be played by an actor of ‘Sydney Greenstreet’ girth) — while ‘megropolis’ has that lovely redolence of ‘grope’ and ‘grot’ (and prefigures the ‘grotzits’ so coveted by Sabalom Glitz in The Mysterious Planet eight years later).

Tom Baker, treating satire as comedy, gives a rather broad performance that lacks the gravity and intensity of Fendahl or Fang Rock, but is not as self-indulgent or as knowing as it would become. Louise Jameson’s Leela does very well in this story, not least because Holmes, noting the tension between her and Baker, kept them apart for large stretches. This allows Leela to shine and the story is Jameson’s favourite from her tenure. The Pygmalion theme is evident again, with the scene of Leela (abetted by K9) playing the Doctor at chess. This story was also briefly considered for Leela’s departure. Louise Jameson had asked to leave and requested an heroic death saving the Doctor. So, Graham Williams briefly mulled having her not survive being electrocuted by the Collector’s safe in Part Four. Intriguing (if hardly heroic) as that death would have been, Williams soon decided it would have been too upsetting for children, forced an unsustainable pause in the concluding part of the story, and would have been impossible to reconcile with Baker’s emotionally distant and ambiguous characterisation. This judgement seems sound.

The other performances in this story vary from good to excellent. Roy Macready’s Cordo convincingly transforms from suicidal drone to freedom fighter as the PCM wears off and so effectively personifies the largely unseen society. William Simons (later a television mainstay thanks to Heartbeat) plays the one-dimensional rebel leader Mandrel well and Michael Keating as Goudry might as well be on his apprenticeship for his later success as Vila Restal in Blake’s 7. Of special note are Adrienne Burgess as the rebel Veet and Jonina Scott as Hade’s deputy, Marn. Both these parts were written as men as Holmes considered women largely superfluous to the Doctor Who format (a stance upheld tirelessly to this day by many fans), but director Pennant Roberts purposefully recast them as women to balance the story better. In Veet’s case especially, this works very well and it’s a pleasure to see a strong woman freedom fighter.

But the two guest performances that dominate are Richard Leech’s bombastic, obsequious, and increasingly desperate Gatherer Hade and Henry Woolf’s marvellously alien and sinister Collector. Hade’s various verbal conceits are very enjoyable (one can imagine him a distant descendant of Henry Gordon Jago) as is his vain pretension to be an historian. Leech nails the character from his first scene to his somewhat camp demise. Despite this, Henry Woolf comes close to stealing the show with his remarkable physical and vocal performance as the Collector: gleefully callous, physically sinister (excellent make-up), and unsettlingly alien. His speech in anticipation of Leela’s steaming — relishing the ‘subtleties’ of her screams, the ‘deeper notes of despair, the final dying cadences’ — is a particularly pleasing example of Holmes’ love of the theatrical grotesque. Woolf would have made a welcome recurring villain and his rapport with Baker is evident. One can also see shades of the Collector years later in another stand-out performance, Nabil Shaban’s unctuous and insidious Sil in Vengeance on Varos and Mindwarp.

The weakness in this story, aside perhaps from the lack of thematic focus, is its somewhat erratic production values. Set designer Tony Snoaden and costume designer Christine Rawlins had wanted to borrow from Mexican propagandist art, which itself drew on Aztec imagery, for their designs. Roberts vetoed this in the main, although the approach still survives in the giant sun that adorns Gather Hade’s office, the emblem on his hat, and on other costumes. It’s a pity not to see the idiom applied more comprehensively, as the BBC presumably had a reasonable amount of scenery and props in stock (not least from The Aztecs in Season 1). It would have produced an agreeable contrast with Doctor Who’s well-worn depiction of the future as high-tech and, if properly resourced, might have prefigured Anthony Masters’ baroque designs for David Lynch’s Dune. Nevertheless, Snoaden’s theatrical, expressionist approach works quite well for the Gatherer’s office, though much less so for the rebel hideout, and the budget’s seams are gaping in the bare corridors, which carry much of the action. The effect is that one can seldom see the Megropolis as a real place, aside from the location filming.

The evident problem is the lack of money. The props also disappoint: the guns lack detail and the satirical ‘Consumcard’ (hastily altered because of Williams’ fear of inadvertent product placement) is absurdly large and not remotely plausible. It’s also obvious that, despite some attempt to hide it, Henry Woolf is enthroned upon a conventional electric wheelchair (until close-up scenes replace that with a commode). The production also overran and the scene of the Collector’s demise, while quite good, was so rushed that Mitch Mitchell would leave the BBC in frustration.

The location work, at least, is strong. The underground passageways at the Camden Deep Tube Shelter (below Camden Underground Station) look good and would be used a couple of years later in the Blake’s 7 story, Ultraworld. The factory roof scenes and some corridor interiors required an unusually distant (for Doctor Who) location shoot at the WD & HO Willis tobacco factory in Bristol. Not only is it an imposing location (though its impact marred by the poor weather) but, for a show about the depredations of an evil corporation, setting some of it among the dark, satanic mills of a drug peddler is a nice thematic flourish.

I wrote earlier that the show is a fusion of two eras. To that extent, the style works against the substance a little, in much the same way as with City of Death, in which Tom Baker mugs his way through lines Douglas Adams intended to be played straight. With The Sun Makers, the performances are also perhaps a little too broad but, in both cases, it’s not enough to truly spoil one’s enjoyment. The script is sharp and funny, if unfocused by having one too many targets. Where it fails is in its physical realisation, which is mostly too theatrical, impressionistic, and – frankly – cheap ever to have real verisimillitude. As such, it plays out less as a drama than as farce. Nevertheless, it’s entertaining and enjoyable. Regrettably, from this point on, the season — like Gather Hade — would head only downward.

Underworld

The first part of Underworld was broadcast on the 7th of January 1978, three weeks after The Sun Makers (a re-edited two-part Robots of Death graced Christmas fortnight). It’s the Bristol Boys’ second script for the season and, for critics of Graham Williams, may well epitomise everything they dislike about his stewardship. The story is a straightforward reworking of Greek mythology, especially Jason and the golden fleece and the Odyssey. The Doctor and Leela land on the R1C, a spacecraft piloted by the Minyans, a people to whom the Time Lords gave advanced technology before they adopted their policy of non-interference. The Minyans nearly destroyed themselves with the knowledge they were not ready to cope with and now the remnants of their race are on a millennia-long quest to recover their only hope for posterity, race banks of genetic material on the lost ship, the P7E.

Undoubtedly, Underworld was mounted in the straitened economic circumstances discussed earlier and, by this point, Williams’ funds were low. To his credit, he conceived a genuinely far-sighted solution: to save building certain sets by making the most extensive use of chroma key (‘Colour Separation Overlay’ (CSO) in BBC parlance) the series had ever attempted. The technique (championed on Who by Barry Letts), involved filming against a blue or green backdrop that was then ‘keyed’ out, allowed a new background to be inserted. In Underworld, Williams used slides of real caves to attempt to create a subterranean feel. Unfortunately, this was the infancy of the technique; erratic, time-consuming, and frustrating for actors and technicians alike. Actors missed their mark and appeared to walk through walls, several times K9 seemingly hovered over the floor, and it vexed further the already turbulent Time Lord. It’s genuinely heartening to see Who continuing its real tradition of technical innovation, but the results here are patchy at best. Some images are quite striking, but the small number of background slides and their rather haphazard use means that the viewer cannot establish a proper sense of spatial continuity during those scenes, something that one does almost unconsciously with a real location. For example, a cluster of three rocks behind characters in one scene will reappear in the background of the next shot as they walk away in the supposedly opposite direction. This sense of unreality quickly fatigues the eye.

The physical sets are impressive for the time, less impressionistic than those erected for The Sun Makers and much better lit than the Bi-Al Foundation in The Invisible Enemy. Certainly, the corridors – such a key ingredient of classic Who – are far superior. Costs are cut here too, but this has an in-narrative justification: the R1C and the P7E are sister ships, so redressing the sets for the former as the latter is acceptable.

The model work for the ships — again produced at the Bray Studios – shines once more. Mitch Mitchell has said that the production team, having seen Star Wars before its December 1977 UK release date, consciously tried to emulate as much as they could on a BBC budget. This includes the extended laser gun battle in Part Four, which recalls the escape from the Death Star. To accomplish this, Graham Williams insisted upon an additional ‘gallery day’ to add visual effects to the footage. The gallery was the control room above each studio from which directors would control the recording. Visual effects would be added, but generally ‘as live’ in a way that seems absurdly primitive today. The extra day was obtained in a studio where the sets were being erected for another production and so its gallery was free. A single laser gun effect would be added to the running videotape, this recorded, and then the newly recorded tape run through again for another shot to be added. By so doing, several laser gun effects could be added to a shot, but at the cost of recopying each time. Sadly, the resultant image degradation is very noticeable in some shots. Nevertheless, we should be grateful to Williams and Mitchell because their innovation stuck: every subsequent Doctor Who serial would be granted an additional gallery day for post-production.

Many of Underworld’s problems were undoubtedly not helped by the inexperience of first-time director, Norman Stewart, who had secured the job on the strength of his previous work on the show as a production assistant skilled with chroma key. He flounders here in the face of choked finances, an even more technically demanding serial than usual, and an increasingly meddlesome leading man who was rewriting the dialogue freely, throwing in his own improvisations, and writing and directing at least one scene himself. But technical challenges and macroeconomic pressures do not excuse this story’s underlying failure: a turgid and underwritten script.

Every one of Underworld’s four episodes underruns substantially, even when padded with repeated shots, extra-long reprises, scenes improvised by the cast, and those that trail on interminably after the dialogue has run out. The worst, Part Two, is a dreary patchwork, including footage cribbed from Part Four and a stultifying, 11-second shot of venting smoke. Baker and Martin had ample space to take their basic plot and people it with rounded characters who exchange involving dialogue. They do neither. Only Herrick leaves any sort of impression and that only thanks to Alan Lake’s forceful performance. The rest have no substance at all. Tala, played by Imogen Bickford-Smith, literally has nothing to do past Part One and Jonathan Newth — a fine character actor – is squandered as Orfe. The Overseers can be entirely overlooked, and the Troglodytes are as convincing as their trogles.

The only memorable line in the whole production – ‘the quest is the quest’ – is so only through repetition and is neither as imperative as ‘Eldrad must live’ nor even plainly descriptive like ‘contact has been made.’ In fact, the cast rewrote much of the dialogue, considering it too colloquial for Underworld’s classically-inflected milieu. If the Oracle (in a solid vocal performance from Christine Pollon) repeatedly instructing her lackeys to ‘get rid’ of the grenades in Part Four is an example of what got through, they were right to do so. Mystifyingly, for a time, the Bristol Boys apparently seriously considered spinning off the R1C crew into their own series of Greek-myth inspired science fiction. On the strength of their debut, they would have been markedly less three dimensional than Ulysses 31.

Overall, Underworld is by far the weakest story of Season 15 (far worse than the widely pilloried Invasion of Time, which would follow) and a plausible candidate for the worst serial of Tom Baker’s reign. There is little to review because there is so little content. It is cheap, peppered with (understandably) insipid performances, skeletally-written, and all this would be forgivable if were not also utterly dull – the one thing Doctor Who must never be. Russell T. Davies has publicly stated his love for this story after watching it as an adult. One can only assume he caught it after a night’s clubbing while still coming down.

The Invasion of Time

The Invasion of Time was beset with problems from the beginning, a hastily written replacement for David Weir’s The Killers of the Dark. This would have depicted a Gallifrey of two distinct peoples: colonists in their citadel who we know as the Time Lords and an indigenous species of cat-like people. Hopelessly expensive and far too complex ever to mount, Graham Williams and Antony Read were forced to drop the script and viewers would have to wait 12 years to see cat people on Doctor Who (30, to see them done convincingly).

This left Williams and Read, in their debut season, staring into an abyss in six parts. They had little time, practically no money, and a scene-shifters strike permitted them just one three-day studio session. In fact, such was their predicament that the BBC offered them the option of postponing the production, ending Season 15 with Underworld, and rolling the remaining scraps of their budget over to Season 16. This was generous by Auntie’s standards, as normally surpluses were returned to departmental budgets, but Williams declined. He reasoned that, such was inflation, the money would be worth even less by the following year. Instead, he claimed on a BBC contingency fund, granting him two weeks of additional location filming, and pressed on.

Williams and Read retained the Gallifrey setting, simply to reuse sets and costumes created for The Deadly Assassin a year earlier. Indeed, they approached Robert Holmes to write a sequel, but he declined, his pen having run temporarily dry (he would return the following year for The Ribos Operation and The Power of Kroll). He did permit use of elements of Assassin (such as Cardinal Borusa) and recommended the 4-2 story structure that had served him so well on The Seeds of Doom and The Talons of Weng-Chiang. In the end, Williams and Read produced a draft script themselves (credited to the prolific but pseudonymous David Agnew), the Sixth Floor have granted Williams dispensation to both write and produce (normally disallowed). Taking only two weeks, Read sent his first drafts to Williams a scene at a time to re-write. Reportedly, Williams produced the final draft in a three-day sleepless frenzy. Gerald Blake, who’d previously helmed The Abominable Snowman in Season 5, would return to direct the show (he’d go on to oversee episodes of Blake’s 7, Play for Today, and Super Gran before his death in 1991).

The basic concept is strong enough and worthy of a season closer (they didn’t really do season finales back then). We join the story with events already in motion as the Doctor strikes a deal with the mysterious Vardans to assist them in invading Gallifrey. He will return to claim the presidency, all the while their man on the inside who will cripple the planet’s defences. Along the way, the Doctor betrays Leela and veers wildly from jovial bonhomie to lofty disdain to fits of wild rage. But is he playing a deeper game against the Vardans? Of course, he is. But, in luring the Vardans to their Waterloo, the Doctor accidentally leaves Gallifrey open to the Sontarans, who then also try to invade.

Invasion is certainly not an unalloyed calamity and there is much to enjoy. There are two guest performances to celebrate. John Arnatt’s regenerated Borusa is a highly creditable successor to Angus McKay’s excellent original. This Borusa is as shrewd and wily as before but Arnatt gives a more understated performance, conveying a lot with very minor facial expressions. His relationship with the Doctor is well played, especially when placed under the strain of Tom Baker’s calculated outbursts. His realisation that the order and logic of his mind — the very characteristics he has cultivated for centuries as strengths – are now a weakness is a particularly strong moment. It’s regrettable that Arnatt wasn’t available to reprise the role in Arc of Infinity six years later (although, in compensation, we did get the indefatigable Master of Ceremonies from The Good Old Days).

By far the most enjoyable performance, at least for this reviewer, belongs to the marvellous Milton Johns as Castellan Kelner. Again, it’s somewhat regrettable not to see George Pravda return as Spandrel, but this Castellan is a much different role. While Spandrell resembled a jaded Chief of Police, Kelner is more the middle ranking civil servant (although, when Part Four requires it, he does show a surprising knack for transduction barriers). Johns, who made a career of essaying Uriah Heap-like characters, plays the scheming quisling with grovelling delicacy, both verbally and physically. It’s by far the best of his three roles in the series (Benik in The Enemy of the World and Guy Crayford in The Android Invasion). I’d like to think that it was a deliberate choice by Williams and Read that his cynical turncoatery receives little comeuppance at the end, that it’s another swipe against Time Lord corruption, but given the pressure they were under, it’s as likely an oversight.

Hilary Ryan’s Rodan also interests, although she’s several drafts short of her potential. As a slightly distant, unworldly Time Lady, she clearly prefigures Mary Tamm’s Romana. Graham Williams wrote an outline of the future companion in October 1977, even while he was still trying to persuade Louise Jameson to stay, so one wonders if Rodan was a prototype. Indeed, had Williams had more time — and more sleep — would Rodan have become Romana, with Ryan in the role instead of Tamm? It seems like a perfect fit, and it would have been pleasing to see Leela build up a relationship with Romana and effectively hand the Doctor over to her care. As a wry aside, I’ll note that at this point Tom Baker was lobbying for his companion to be a cabbage that would sit on his shoulder ‘while making wry asides’.

The rest of the guest cast are unremarkable. Christopher Tranchell’s guard captain, Andred, is blandly written but agreeable enough. Leela gets a tribe of wannabe warriors outside the Citadel to inspire but they might have trudged off into half a dozen episodes of Blake’s 7 and nobody would have noticed. The Vardans are consistently dismal, be they disembodied voices heard through the backs of chairs, shimmering energy creatures, or a trio of uniformed humanoids. In their first two manifestations, this is largely down to Stan McGowan, who reads his lines as if he’s giving a PowerPoint presentation on the wide variety of pipe gauges available for domestic boilers. Visually speaking, in either their chair or Bacofoil forms, they are merely dull, but as humanoids they are truly ridiculous; cursed as they are with uniforms that even the Tracy Brothers would have rejected as ‘a bit camp’. Moreover, after four episodes of building them up as a menace capable of conquering the Time Lords, the perfunctory ease of their eventual despatch (the second time loop of the season, time loop fans) makes the resolution about as thrilling as fitting a screen protector. Unfortunately, things do not improve with the pivot at the end of Part Four, when a weakened Gallifrey is then overrun by a legion of three Sontarans. They too are risible, thanks to a miscast — and sh*t-masked — Derek Deadman as Stor. Williams reportedly made several requests to Deadman to not play it in his native accent but to no effect; and so the viewer is subjected to a Sontaran gangster who has seemingly wandered out of that film Guy Ritchie makes every couple of years.

Mention of the Sontarans brings us to three of the more controversial elements of the story. The two weeks’ extra location filming Williams secured took place at the disused St Anne’s Hospital, which they used for several sets including the TARDIS corridors (the pool was filmed at the British Oxygen building in Hammersmith). This has rightly disappointed fans over the years; however, while incongruous, these corridors are no more disappointing than those created for The Doctor’s Wife 34 years later – which are so dull they look like the tunnel Adrian Chiles would see while having an out of body experience. Far better is the notion that various pieces of TARDIS machinery would appear as sculptures and paintings. It’s an ingenious and cost-effective idea that really conveys the notion of a society millions of years ahead of ours. It could have betokened a wider reimagining of the Time Lords more alien that Holmes’ retirement home for dusty senators.

A more modern controversy is the final resolution of the story, the De-mat Gun. Arguably, this is disappointing in storytelling terms — the sort of failure of imagination one would expect from writers with nothing to keep them awake but panic and the infamously homeopathic BBC coffee – but ethically it’s no more objectionable than the explosions that crown so many other stories. The Doctor ‘who never picks up a gun’ is a modern conceit that does not disguise the reality that the Doctor routinely engineers things and people to be weapons of equal lethality. Thus, logically, the Doctor clutching a rifle is not necessarily morally objectionable so much as aesthetically displeasing.

What is inexcusable is the undignified departure inflicted upon Leela. Her arbitrary decision to stay on Gallifrey with Andred is absurd. Tranchell and Jameson both do what they can throughout the story to convey some sense of growing attraction between the lines but cannot spin gold from straw. The blame for this lies with Graham Williams. Despite plenty of notice and repeated confirmation, he would not accept that Louise Jameson wanted to leave or, until very late in the production, that he would be unable to persuade her to stay. He later admitted that, when he finally accepted she was going, he wrote her departure in a fit of pique. It is an abysmal farewell for Jameson and the second in a row because, as Philip Bates notes in his review of Season 14, the pretext for Sarah Jane’s departure in The Hand of Fear is also a ‘cop-out’. Leela’s exit is worse, however, because while Sarah Jane leaves as the result of a mere plot contrivance, the ‘romance’ with Andred is lazy and damages her character. This ‘marrying off’ was patriarchal and condescending when perpetrated on Susan at the end of The Dalek Invasion of Earth in Season 2 and still hackneyed (if much more believable) when done to Jo Grant in Season 10’s The Green Death. Still, this glaring failing aside — and taking the story as a whole — at least with the rebels Leela gets a subplot to herself and is given several strong moments. Her faith in the Doctor, even when he seems to have betrayed her, is convincing and touching without being mawkish.

Leela deserved better, but at least Louise Jameson received a fitting salutation: the production team gifted her a (real) knife, engraved with her Doctor Who dates. She also kept her original Leela costume (bonus trivia point: the second costume would be worn several years later by the sainted Floella Benjamin during an edition of Playaway).

In sum, The Invasion of Time is superior to the turgid Underworld, but still well down on the previous closer, the (admittedly heavily overspent) The Talons of Weng-Chiang. The script contains all the elements of a very successful story. We have an alien menace so great that even the oldest civilisation is in peril. We have the Doctor’s change in character and subterfuge, a conflict with his old mentor, the wrenching apart of his friendship with Leela, her eventual departure, and a new companion. The cliffhanger to Part Four – in a world before internet gossip and set report vandalism – could have been one of the best the series had ever produced. Indeed, it’s a shame they didn’t go for broke and write in a third invasion, with the Sontarans overhauled by the glorious Rutan army – thereby bringing the season back to its beginning and giving a young Welsh lad a vital lesson about the perils of over-cooking your finales. At the end, the Doctor and Rodan could have flown off in the TARDIS together and straight into an end of season cliffhanger: a bright white light and a booming voice: ‘beware the Black Guardian.’ But no, the potential is lost. The script was born premature and weak and the production is gaunt and tired, mitigated only by several strong performances. Quite simply, there isn’t the time or money to do some interesting ideas the justice they merit.

Conclusion

With The Invasion of Time, the new Doctor Who production team limped over the finishing line, exhausted and broke, but having successfully delivered their debut season. As Russell T. Davies, Julie Gardner, and Phil Collinson would have put it, they ‘held the line.’ For that, they deserve respect and gratitude.

Looked at in isolation, Season 15 is variable but mostly enjoyable. Horror of Fang Rock stands tallest, closely followed by Image of the Fendahl and, some way behind, The Sun Makers. The Invasion of Time – with superior characterisation and performances – easily beats The Invisible Enemy for fourth. Underworld should be consigned there.

Thematically speaking, one should be cautious about reading too much into a collection of stories by different scribes, written under very different circumstances. Despite that, one can certainly see imperialism (and its mechanism, colonialism) as an underlying preoccupation. It’s most clearly stated in The Sun Makers and undergirds Fang Rock but is also there in The Invisible Enemy; openly, in the colonising Swarm’s macroscopic maraudings, but also in the story’s notion of having one’s genetic material ‘occupied’ (foreshadowing some of the GM technology and ‘biopiracy’ controversy decades later). The notion of colonisation is also present, if muddily formulated, in Image of the Fendahl, while The Invasion of Time needs no interpretation and does not ask to be read politically. Underworld obviously features a crew of aspirant colonists in search of another, but that story is too pallid to feel like a consideration of any political theme. Of course, alien invasions feature quite heavily in Doctor Who, so one should be careful not press the point too far, but Britain’s decolonisation during the 1960s (the ‘wind of change’) must have been an issue warm in the public mind.

Viewed in the context of the classic series as a whole, Season 15 looks like a pivot and the beginning of a slow decline. The ratings would hold up for several more years to come, but it’s here that the end was born. While there would be many, many more great stories to come, there would never be whole seasons of consistent high quality like 12, 13, and 14: every Earthshock would be followed by a Time-Flight, we’d experience a Revelation of the Daleks only after suffering an Attack of the Cybermen, and we’d have to cross a Battlefield to reach the Ghost Light.

There are several simple reasons for this decline. One is that the series’ budget, even allowing for ’70s inflation, could not keep up with the programme’s aspirations. On its own terms, it couldn’t deliver as it had previously, but it also began to suffer from the competition. With Star Wars hitting the cinema and imported American shows like Battlestar Galactica, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, and Space: 1999 landing on ITV, it was no longer only the Time Lord offering teatime adventure. And, although the production team made serious and quite successful attempts to revamp the programme’s image from 1980 onward, it wasn’t only the TARDIS that began to wheeze and groan. Much of this damage was done from Season 15 onward, because the more outlandish and risible sets and effects stuck in the popular imagination for the rest of the century (and one could play that opening model shot from Trial of a Time Lord as often as one liked; it only served to show up much of the rest of the visuals for the bargain-basement rubbish they too often were). This also stuck with the BBC, who lost what little faith they had in the programme.

Another reason for the decline was the step away from the robust storytelling of the Hinchliffe era to the Age of the Tin Dog. Doctor Who spent the remainder of the 1970s as little more than pantomime and, despite some remission under John Nathan-Turner — and Andrew Cartmel’s laudable blowing on the embers — within popular culture, remained little more than a punchline until Russell T Davies midwifed its rebirth.

But the mistake with most far-reaching consequences for the future of classic Doctor Who was to not replace Tom Baker in Season 15. Admittedly, this was not solely in Williams’ gift, even as producer. The much denigrated Sixth Floor would undoubtedly have looked askance at Williams for wanting to replace a wildly successful leading man in a wildly successful show but, had Williams pushed for it, this would have given Baker a final year in the part while he was still engaged and relatively self-disciplined. The advantage of this would have been that, while we could still celebrate Baker’s unparalleled success in the part — for, truly, he was a giant — he would not have cast a 30-year shadow over his successors. A Fifth Doctor in 1977 would not have had quite the mountain to climb that faced Peter Davison in 1980 and the series might have gone into that decade stronger. Not only that, but Baker’s own career might not have suffered quite so much in the aftermath. Season 15, then, though nobody could have seen it at the time, was the beginning of a new phase of classic Doctor Who but the quiet, unheralded beginning of its end.