1981: when Bucks Fizz won the Eurovision Song Contest with their immortal ballad Making Your Mind Up, when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister and Mr and Mrs Sunak delighted in their tiny toddler (name of Rishi), when John McEnroe told the Wimbledon umpire, ‘You cannot be serious!’, and one Arthur Scargill was elected leader of the National Union of Mineworkers. In the year 1981, say I, it came to pass that Madame Tussaud’s did open The Doctor Who Experience.

Doctor Who was then in a state of transition. John Nathan-Turner had just produced the tonally innovative Season 18, Tom Baker had bowed out after seven years in the role, and Peter Davison had just been introduced to the world as the new Doctor at the end of Logopolis. Some fans welcomed the changes; others loathed them and grumbled that that bloke out of All Creatures Great and Small was too young, too blonde, too well known, and above all was not Tom Baker. (NB: Doctor Who fans have always hated Doctor Who.)

Doctor Who exhibitions were not new in the UK. Fans of a certain vintage will remember nagging their parents to take them on pilgrimage to the permanent displays at Longleat and Blackpool. The Doctor Who Experience, though, was different: Madame Tussaud’s used their own workshops to create original waxwork likenesses. Some of these were superb, some less good, and all were displayed in what was in those days a state-of-the-art son et lumiere environment. (Madame Tussaud’s had, of course, featured in Spearhead from Space, but these waxworks did not come to life and gun down visitors going whirr whirr whirr whirr oing pu-chang! hahahahaha.)

Frank and I, then fifth formers about to take O Levels, took time out from our busy revision schedules, learning of the mysteries of soil creep, longshore drift, and German irregular verbs, to travel up to our mighty metropolis to meet and interview those responsible for the exhibition. What follows is the write-up from Fendahl 15, originally published in April 1981. It’s been slightly tweaked to remove some of the infelicities of the prose, but it’s still jolly interesting. Hope you enjoy it.

Where Autons Dare…

Madame Tussaud’s is a few yards from Baker Street Underground station. The reception office was a bit difficult to find with brains numbed by the cold, yet we entered and were met by the press officer, Juliet Simkins.

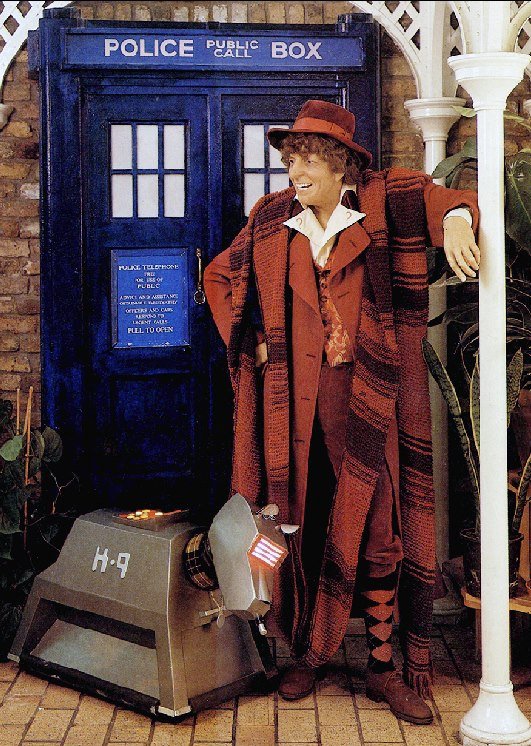

A short jaunt in the lift brought us to The Doctor Who Experience on the second floor. Tom Baker’s smile guided us to the entrance. The waxwork of the Doctor was remarkable; Tom was leaning against a pillar, wearing the Colgate grin we’ve come to associate with him. The replica of K9 ticked quietly away to itself at his feet.

The designer of the experience, Michael Wright, was our guide.

Michael Wright: “I didn’t actually make this wax figure. I run the design studio; studio one is the portrait studio; I run studio two. In fact, the Doctor Who exhibition we’re about to go into had some outsiders brought in, though most of it was built by studio two. We did, in fact, have the sets built outside to our specifications. John Nathan-Turner and BBC Enterprises [the BBC’s commercial arm in the Eighties] were very helpful; they provided many photographs of previous series. We used the last television series as the basis for our exhibition, with the Nimon and the Dalek. Plus some from this season too. I actually went down and saw Meglos and Full Circle being made – very interesting to see how they handle their own problems. The camera, of course, doesn’t pick up as much detail as someone who’s walking about this exhibition, so although we were able to use the basic ideas, we had to think again when looking at the settings.

“The Doctor Who figure was made by Judith Craig. We use it as an introduction to The Doctor Who Experience, which is why it’s outside in the Conservatory. When the exhibition finishes, it will probably stay in Madame Tussaud’s [it did] with K9 [it didn’t].”

Did Tom Baker come along for sittings?

MW: “Oh yes, he did. This was enormously helpful. Normally we have only one sitting, when we take photographs from about eight different angles, all round the head, and we also take caliper measurements. Then we match up eye colour with glass eyes – we have an enormous stock of them. We match up the hair as well as deciding on the pose. Then the sculptor goes away and models in clay, using the measurements and photographs – as well as the impression given to him by the subject. The pose was chosen because it’s simply very much him: you know, very characteristic. It’s usual to have the pose decided upon between the sculptor and the model. It’s very relaxed, to match the relaxed atmosphere of this particular room.”

We’ve heard that there were two heads made for the Doctor, one of which didn’t catch Tom Baker’s likeness. You also have a figure of the Meglos doppelganger; did this use the other head?

MW: “No. The sculptor who made the first head did another one. With Meglos, we had to add all the bumps and prickles; besides, the expression and pose are completely different.”

Was there any reason why you chose Doctor Who out of all the other popular science fiction shows?

MW: “I think because it’s a British production, it’s a very long running series, and it’s been shown all over the world. It’s run for seventeen years, and there’s no reason it shouldn’t run for another seventeen. The trouble with things like Star Wars is they tend to be fashionable. Most people, I would think, do watch Doctor Who at some point; we were aiming to produce something for children and for British visitors. So, having got the necessary information from the BBC, it was a matter of translating those elements to the Experience. Because they have so many sets and aspects to each programme, we had to select the key elements and transfer them to the area we have here.”

The K9, we guessed, had been supplied by BBC Enterprises.

MW: “That’s right. They also supplied us with a number of costumes. For the Doctor figure, the coat and scarf were all made by the people who made the Doctor’s costume on television. With some of the exhibits we have here, such as the Nimon, the Sontaran, and the Marshmen, the costumes have been lent to us by BBC Enterprises.”

Did Lalla Ward come for sittings as well as Tom?

MW: “Yes. The costume was again lent to us by Enterprises, and sculptor John Robinson made the figure. We start with a basic metal armature which is the skeleton, if you like. You wrap the metal frame with wire mesh; once you’ve got it in the right pose, and you put clay onto that. The sculptor models the complete figure. The head is then cut off, moulded in plaster and cast in wax, and the body is cast in fibreglass.”

The voice of the Sontaran coaxes us into the exhibition; to enter, we had to pass through two huge police box doors. The sign, ‘Police Public Call Box’ flashes on and off.

MW: “One of the problems here was not only to create something that looked like the TARDIS, but which allowed people to walk through it. As a design feature, then, this TARDIS is much bigger than it is in reality. The TARDIS walls lining this section were designed by us, and built under our direction.”

The TARDIS scanner was open, revealing the new logo. Passing down the corridor, we came to Field Major Styre, facing his screen from The Sontaran Experiment. I was rather startled to see myself appear on the monitor, as Styre announced, ‘Analysis of the humans reveals that they are puny beings, dependent on chemical and organic intakes.’

MW: “We modelled all the figures ourselves, because we found that the masks used by the BBC are obviously intended to go on an actor’s face and are intended to move. Well, when you put that on a figure, it doesn’t work in the same way. So, for instance, we found we had to use the basic idea of a Sontaran and our sculptor set to work. We built the whole exhibition in 12 weeks, from design to finish, which is pretty good going. As for the Sontaran: we recorded a soundtrack from when Styre’s talking about his experiments. Then we have the video camera linked up to the television screen so you get the impression the person he’s experimenting on is the visitor. This set was adapted from the actual interior of one of the spaceships. It’s based on the one used by the BBC but very loosely, because it was only shown for a matter of seconds on screen.”

Turning round, you could see the Meglos doppelganger figure, staring at the Dodecahedron in his palm. The voice of Lexa [she was played by Jacqueline Hill, you know] boomed: ‘This is the control command. Arrest the Time Lord! Stop him at all costs!’ And then the figure bellowed, ‘I am Meglos!’

MW: ‘What we wanted to do was to take a part from the story when Meglos’ hold on the Doctor was slipping, and he was running away, having just stolen the Dodecahedron. To illustrate its power, we show it as part of him, which is why he glows as though the power’s running through him.

“The bristles were the most difficult part, actually. In the end, I used a normal nylon sweeping brush, and dipped it in green dye.”

In a niche off the corridor, the superb Romana figure stretches out her hand to meet that of a Marsh Creature.

MW: “The Marshman is the one used on screen. For all the others, we took the basic shape and modelled the figure ourselves. This is the original dress Lalla wore when shooting Full Circle. Lalla and Tom have now become the only husband and wife team in Madame Tussaud’s – apart from the kings and queens, of course!”

The corridor widened out into a larger room.

MW: “In this second area, the environment changes around you. It was designed by my colleague, James Copp. The whole thing about this is that it involves the visitors personally. That’s why we’ve called it “The Doctor Who Experience”: we want people actually to be part of it, as though they were actually there.’

A blaze of red light suddenly illuminates the Nimon, synchronised with its bellowing roar. Several wax Anethans sleep in their pallets, dressed in the original costumes.

MW: “The Nimon is the actual BBC costume, but the head was modelled by one of our artists.”

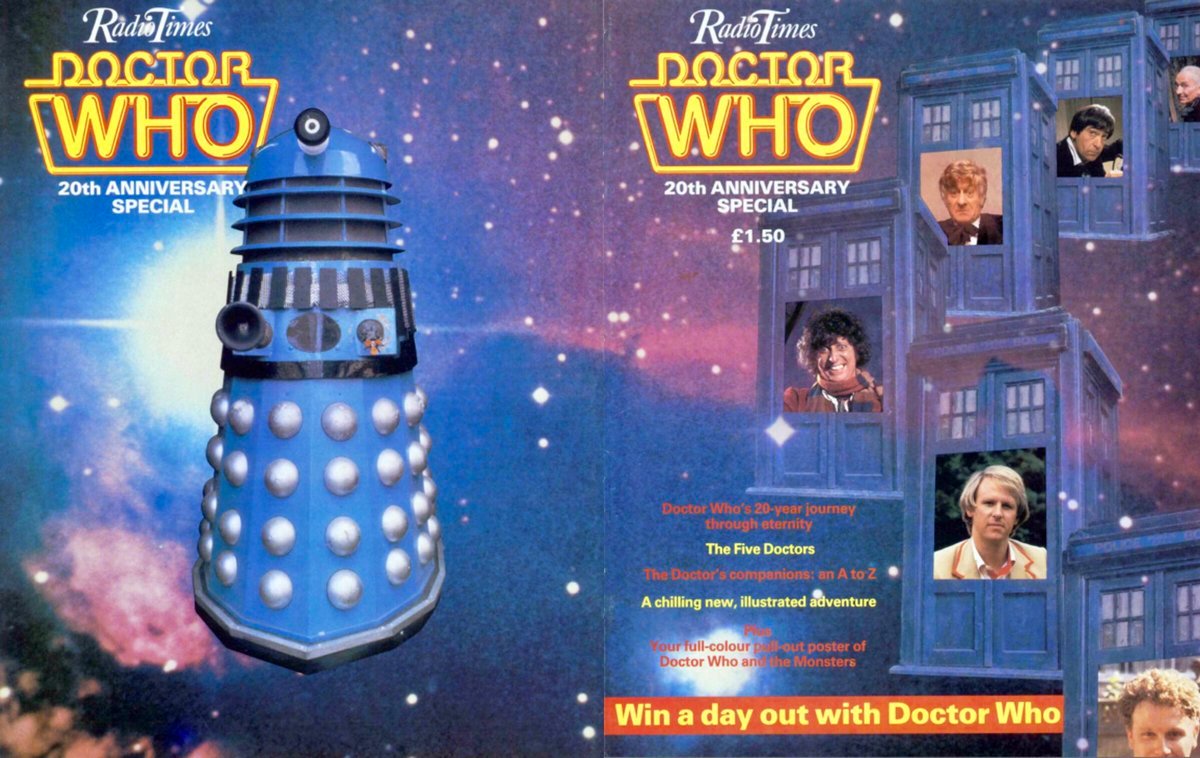

A blue and silver Dalek chanted some lines from Destiny of the Daleks. [For purists: the colour scheme was never seen in the series; it was repainted for the exhibition. The Dalek can be seen on the back cover of the Radio Times’ Twentieth Anniversary Special. It was later used as the Dalek Supreme in Resurrection.]

MW: “That’s from the BBC. They refurbished it for us, and we put in the lights and sound.”

Nearby, two panels from Destiny pulse away softly. One contains the illuminated map of the Kaled city; in the other, someone was shouting, ‘Today, the Kaled race is ended, consumed in the fires of war! But from its ashes shall rise a new race: the supreme creature, the ultimate conqueror of the universe, the Dalek!’ A superb exhibit, harshly lit, and far better than either on-screen version.

MW: “This was modelled by one of the sculptors in the studio. The map is fluorescent; it’s lit with ultra-violet, which gives it that unearthly appearance.”

We comment that it’s far better than the BBC’s Davros.

MW: “Yes, but we have an advantage. Their problem is that the creature has to be a mask; it has to be made in a way that actors can talk and breathe through it. We can take the idea, and make it in exactly the same way as we would do with a wax head. Davros has a wax head and a fibreglass body, just like the rest of our collection. This was one of the things we wanted to do; to give the impression that these things actually exist; if they could, they would get out and walk among us. So we give the feeling that it lives.”

This is the third Doctor Who exhibition. Do you have any competition from Longleat and Blackpool?

MW: “Not at all. We worked very closely with BBC Enterprises here. The Blackpool and Longleat exhibitions use the real props. There are two Nimons at Blackpool; there was one costume spare, which we made the head for. One can only say how important BBC Enterprises’ help was, and how marvellous they were. Without their help, and the help of all the Doctor Who production team, we’d never have produced an exhibition at all. They were simply tremendous.”

The final exhibit was a Foamasi. Slightly smaller than its television counterpart, the head barely reached the four feet mark.

MW: “This was modelled by John Robinson, who also did the Lalla Ward figure. It’s made of fibreglass.”

The Doctor Who Experience is unique; you can feel that by looking at the hesitating figure of Meglos, you are in the dark corridors of Tigella. You become a living part of the story. Congratulations to Madame Tussaud’s for taking a bold step, and for brilliantly succeeding.

Article by Frank Danes; original interview by Frank and Simon Danes. Thanks to Michael Wright and Juliet Simpkins for all their help. Contrary to rumours, the Doctor Who Experience remains open to the end of this year [1981].

Sadly, very few pictures survive from The Doctor Who Experience. We’ve reproduced two from the original article in Fendahl; they’re of very poor quality but they give you some impression. In those days – this was more than 40 years ago! – the images were about as good as you could get for a photocopied fanzine; they had to be scanned by a process called dot screening to stand any chance of being reproduced. Hence the dottiness. The original photos we took have long since vanished.

If anyone else went to Madame Tussaud’s in 1981 and took some photos, do please upload them in the comments section below — we’d love to see them!