Like the slasher sub-genre in horror films, Doctor Who has always had a large LGBTQI+ following. But why? It wasn’t until the show came back in 2005 that we had openly gay characters in the TARDIS. Indeed, throughout the original series, which ran between 1963 and1989, things were very different, even down to the fact that the producers didn’t really like the Doctor hugging companions for fear it might imply there was some hanky-panky going on behind those Police Box doors. We’ve had a few companions and characters who are openly gay or whose sexuality is pretty fluid like Captain Jack, River Song, Jenny and Vastra, Clara, Bill, and Yaz. Even at the end of the original series, Ace was believed to be bisexual. But having supporting characters being openly gay is pretty rare so with not much in the way of representation, just why do so many in the LGBTQI+ community love Doctor Who?

Before we start, I want to state that this isn’t an attempt to be a social justice warrior. The subject of LGBTQI+ topics will always be a tough pill for some people to swallow. All I ask is that you read with an open mind. I’m not going to say that there haven’t been any LGBTQI+ characters in Doctor Who and I’m not going to sit here and write that some of the messages in the show haven’t been a little too preachy. And I’m certainly not expecting anyone reading this to agree with my thoughts and opinions. What I do hope is this is going to be a fun look at Doctor Who through an LGBTQI+ lens and that it will look at aspects of the show you might never have considered before.

When I first started writing this, I wondered where to begin. Should I go back to 1963, or start with the 2005 revival and work backwards? In the end, I decided that, like all great stories, it’s best to start from the beginning — so let’s cast our minds back to the junkyard of 76 Totters Lane and the discovery of the strange machine that can move anywhere in time and space…

The UK was very different in 1963. It was still illegal for two men to be in a relationship; that would later change in 1967 but even then, there were people who worked behind the scenes who had to hide who they were. One person who had to do that — though it was known to the original producer and creator of the show, Verity Lambert — was director Waris Hussein, who helmed both the opening story, An Unearthly Child and later story, Marco Polo. Speaking a few years ago with The Doctor Who Fan Show, he said that Doctor Who was originally created as an adventure series to be watched by children; discussions on LGBTQI+ themes didn’t exist in the same way they do now and there would never have been room in these stories to have those conversations. But there were chances to have characters interpreted in a certain way. Looking at Marco Polo, he said the villain Tegana, glad in tight black leather with his hair slicked back, as opposed to Mark Eden’s square jawed portrayal of explorer Marco Polo, could be seen then as a sort of fantasy figure for some gay viewers. For Hussein and his experience with Doctor Who, this was the only way these themes could be included in the show.

1965 saw actor Max Adrian guest starring as King Priam in The Myth Makers. Adrian was an openly gay man who had been arrested in 1940 for the crime of ‘importuning’, a charge at the time used to target gay men. At the time, even something misconstrued as a flirtatious smile could result in this charge and Adrian served three months in prison for this. Unfortunately, there are stories of William Hartnell being horrible to Adrian at the time because of this. As much as one doesn’t wish to bad mouth the original Doctor and the man who played him, Hartnell’s real-life granddaughter has spoken about how sometimes, Hartnell’s attitudes weren’t well received by his cast mates. While I’m not condoning these actions, we do have to remember that Hartnell was born in 1908. The attitudes of the swinging sixties could be very different from 1908; clashes about things like sexualities were bound to crop up.

One might think that there wasn’t any other representation for the LGBTQI+ community in the 1960s but let’s look at the second ever story, The Daleks, the first appearance of the most iconic baddies — if not only in Who, but surely one of the most iconic in all of science fiction: the Daleks. In 1963, it had been just over 20 years since the beginning of World War II, which saw the Nazi party trying to exterminate anyone who didn’t conform to their ideals. How terrifying would have it been for viewers to hear the word “Exterminate” being chanted over and over again, especially on what was described as a children’s show?

Ignoring the Daleks for a moment, the other species in that story are the Thals, cousins of the Kaleds — (what’s that an anagram of?) who the Daleks are trying to destroy with another neutron bomb. The Daleks have no reason to pursue the Thals, other than they are different from them and the Doctor isn’t going to have that. From the second televised story, there is a strong sense of justice about the Doctor, doing what’s right; treating all life in the universe with respect has been a large part of the Doctor’s character as well as a driving force for the show, even in times when LGBTQI+ themes couldn’t be included. This is possibly why so many people from different communities and walks of life love the character so much.

Looking at the Daleks and their desire to exterminate anything that isn’t like them, this can most definitely be looked at in a way that reflects how LGBTQI+ communities have been treated. Let’s not forget who the Daleks were based on and their xenophobia was inspired by the Nazis’ anti-Semitism. Nothing about the Daleks’ inspiration is subtle. Much of British television throughout the ’60s and ’70s was stuffed with antifascist themes. The heroes of many shows were up against fascists and Nazis — one can’t get a more perfect example of a villain. The Daleks have always been a great way of teaching viewers the dangers of fascist ideals. Throughout the early 1960s, the Daleks were the ultimate villain, constantly trying to kill anything that isn’t like them.

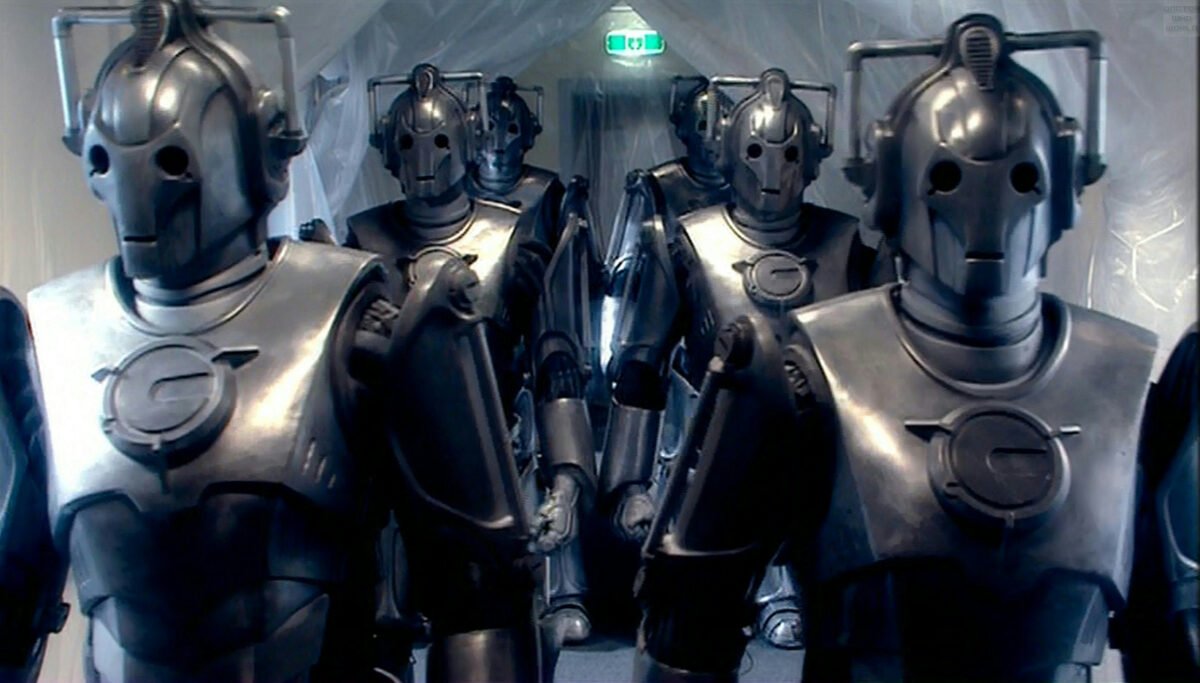

The Daleks are a nice segue into the Cybermen. While the Daleks are racist pepperpots, it’s always been pretty easy to defeat them: just round them up into one place and blow them up. The Cybermen, however, prove a bigger threat — in the real world too. The Cybermen’s ideals, making the universe the same, is perhaps even more dangerous. As the Cybermen famously say in The Tomb of the Cybermen, “You Will Be Like Us.” To further explore this point, let’s look at this line of dialogue from Doomsday:

“Cybermen now occupy every landmass on this planet. But you need not fear. Cybermen will remove fear. Cybermen will remove sex and class, colour and creed. You will become identical. You will become like us.”

This desire to remove what makes one an individual is more terrifying than anything Doctor Who has created elsewhere. The idea that you will become a corpse walking around in a metal suit is terrifying. The Daleks are the ultimate fascists; the Cybermen could also be viewed as an example of communism taken to the extreme. While they want to remove individuality, they also want to become the ultimate equality. No one is different; no one will have more than the other; there are no more emotions and everyone looks the same, which could be seen as a much more radical idea of a communist society.

Before this turns into a political chat, LGBTQI+ communities around the world couldn’t survive without individualism. You can destroy every Cyberman but their ideology will always survive them. It’s an ideology that is still shared with many individuals, countries, and cultures around the world — that everyone should conform to the societal norms laid out by centuries of history. People should be allowed to be whoever they want to be, wear what they want, look how they want, marry and love whomever they want. But as with laws around the world, this doesn’t seem to extend to the LGBTQI+ community. And those societal norms are much like the Cybermen’s need to convert all living matter into versions of themselves, that anything different should be destroyed. Again, much like the Cybermen’s ideologies, so long as there is bigotry and prejudices in the world, there will always be the dangerous seeds of hatred and jealousy.

In 1967, things began to change (even if they didn’t get much better), with it no longer being illegal to be in a relationship with another person of the same gender. But the Doctor continued to fight for justice no matter who you were. One might think there wasn’t any representation throughout the 1970s. At first glance, this could prove true but let’s look at one of the shortest running companions and a line of dialogue from one of the most popular stories from the show’s history.

In Spearhead from Space, we are introduced to Liz Shaw, who becomes the Third Doctor’s companion throughout his first season. Brave and intelligent, she works as a scientist for UNIT, though reluctantly. Of course, like Waris Hussein had said of the 1960s, the 1970s didn’t really leave much room for LGBTQI+ themes or character development. But this changed in the 1990s — or the Wilderness Years as some call them — when a series of hour-long films, written by Mark Gatiss, were released straight to video. These films saw Liz Shaw working for PROBE with her boss Patricia Haggard. Not only did these films feature the first same sex kiss between two men in Doctor Who continuity, but in 2014’s PROBE movie, When to Die, we see Liz now in a relationship with Patricia, making her the first on-screen companion to be depicted as gay.

Then there is the famous line from City of Death. The Fourth Doctor tells the Countess, “well, you’re a beautiful woman – probably.” Many fans have taken this line to mean that the Doctor is asexual, meaning he has no interest in men or women in a romantic way. This would change in the modern era, but viewing the Doctor as asexual would fit with producers’ interest in making sure that the Doctor doesn’t do too much comforting of his companions for fear of it being misconstrued. Whether you agree or not that this could be what the line from City of Death meant, I’ve always taken it as the Doctor just being cheeky.

By the time the 1980s rolled around, Doctor Who had become loveably camp. It was bright and colourful, full of glitz and glamour. The inclusion of stunt casting under the eye of producer, John Nathan-Turner, certainly added to the air of camp. That sensibility could have appealed even more to LGBTQI+ viewers. The line the Rani shouts at the beginning of Time and the Rani — “Leave the girl, it’s the man I want” — has become a favourite and something said quite a few times at various conventions I’ve been to over the years.

Fourth and Fifth Doctor companion, Adric, was also played by someone who was out, though it was kept from the public. In an audio book, A Full Life, Adric is confirmed to be bisexual as he’s been married to both a woman and a man. Any discussion of a character’s sexuality couldn’t be had in the show, not only because there was no room for it in the stories but also because of a bill in American law that would not allow homosexuality of any kind to be depicted on-screen in a good light. Although this was an American bill and not a British one, it did travel overseas. Knowing this, one might look at the death of Adric with a modern lens and wonder if this was a way of making sure a possible LGBT element didn’t end well. This is just one way to view his death; the story makes it clear he sacrifices himself to stop the Cybermen, but thanks to extended media, this could be a new way to look as to why he was written out of the series in such a fashion.

Keeping with that modern lens, let’s turn to the 1983 story, Terminus. In that story, the Fifth Doctor and company arrive on a ship heading towards the titular space-station. They find out that people are being treated for Lazar’s disease and when Nyssa contracts it, she and the Doctor must work out how to cure it. At the time of airing, one of the greatest crises in LGBTQI+ history was well under way: that of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus or HIV, of which AIDS is the final of the three stages that the virus travels through. Treatment and stigma of those suffering and dying from the virus, whether they were gay or straight, was shocking and similar to the way people in Terminus treat those with Lazar’s. On the surface, Lazars is a leprosy-like illness with one character even shouting, “this is a leper ship, we’re all going to die!” However, it’s hard to imagine that author Stephen Gallagher wouldn’t have been aware of the AIDS crisis then, the first confirmed death having occurred in December 1981.

Things only got worse from there with political involvement really ramping up fear of the disease. The same year as Terminus aired, the BBC aired Killer in the Village, looking at the disease, theories on it, and early ways of treating it, no doubt though many just attributed the name of the documentary to the virus without actually learning how it was transmitted or caught. One way that HIV/AIDS could be caught was through the sharing of needles, notably those used when taking drugs. One could look at the Vanir, the group tasked with keeping the Lazar’s under control, dying from their addiction to Hydromel, an expensive cure for Lazar’s could be another analogy for the ways people believed you could die from AIDS. This is made even more prevalent when we see how the other Vanir treat Bor, an elderly man who is slowly dying from his addiction. He’s treated as an outcast, hated and feared by the other Vanir in a similar way that the public treated those who contracted HIV/AIDS.

Hydromel could also be seen as a precursor to Prep, a tablet now available on the NHS which can offer some protection against HIV/AIDS. Not made freely available in the UK until 2020, like Hydromel it was a drug kept only for those who could afford it. Nyssa then leaves the Doctor to find a way to create Hydromel so that it loses its financial value and allowing people who wouldn’t be able to afford it have access to it in much the same way that Prep is now.

Also opening the 1983 series of Doctor Who was Arc of Infinity, in which we see Tegan’s cousin Colin and his friend Robin travelling around Amsterdam. Fans and viewers haven’t been blind to the homoerotic subtexts here. Robin asks Colin why he’s going to sleep in his clothes and the opening scene has the feel of something from an adult entertainment film. And they had a hostel room booked together, though we don’t know if this is a room with a double bed or singles!

Before we get to the late 1980s, when there were a number of stories featuring LGBTQI+ undertones, let’s have a look at some of the production members, most notably Peter Grimwade and John Nathan-Turner. Grimwade was a production assistant, writer, and director on the show. He penned three stories throughout the Peter Davison era and directed two Fourth Doctor stories from Tom Baker’s last series and two from Davison’s first. He was openly gay. Both his stories from Davison’s first series are considered two of the best directed stories of the 1980s (though of the three stories he wrote, only Mawdryn Undead is particularly good).

Nathan-Turner’s sexuality was publicly known and he was in a relationship with Doctor Who‘s production manager Gary Downie. He was famous for wearing very flamboyant Hawaiian shirts, which made him an instantly recognisable figure. Under his time as a producer from 1980 to 1989, the show gained a rather camp air about it, something that wasn’t notably around under other producers. Perhaps “camp” is the wrong word, but it definitely takes on a pantomime feel during this time. People often criticise him, blaming him for the show’s eventual end, ignoring the input of the then-director general Michael Grade. He doesn’t get enough credit for keeping the show going as long as he did, especially at a time when the BBC was doing everything it could to cancel the show.

There are a couple more moments when characters could be interpreted as being part of the LGBTQI+ community during the Davison era. Some people believe that companion Turlough might actually be a gay character. I’ll admit at first I scoffed at the idea. If anything he was written to be as asexual as the Doctor, but actually thinking about it, Turlough is the first companion where it is easier to read as being homosexual than any other. There have been undertones to previous companions, but there had never been a companion so consistently conceptualized with gay tropes… unfortunately, mostly bad ones. One of them is that he has been exiled to Earth to an all-boys school and is seen leading his friend to temptation and ruin. But in Enlightenment, he is thrown to the ground by a rather strapping gentlemen and is facing someone in leather boots, being told to crawl. (You’re not telling me that scriptwriter, Barbara Clegg, didn’t know what she was doing!) Those boots belong to Lynda Baron’s Captain Wrack, who in rather camp fashion tells him he’s just what she’s been waiting for, before waving a sword around her in a way that would make Leatherface in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 blush.

There is an air of authorial intent from John Nathan-Turner when it comes to the character of Turlough. I’m not trying to use Nathan-Turner as the way that Doctor Who was trying to promote a “gay-agenda” in the 1980s; the producer actually found himself at the end of some terrible homophobia from various fanzines that were published at the time. But if John can’t be taken as one of the reasons for some of the LGBTQI+ undertones in his era, then he had to at least be a party to it. Looking at Turlough, there is little way anyone who knew anything remotely about gay culture at the time couldn’t have noticed that the character was being presented as gay, especially in his first three stories.

It’s a shame, then, that if there were some homosexual themes to the character, most of them were negative: Turlough feels like a stereotype of a gay man, someone who has rather cosmopolitan tastes — the first thing we see him doing is admiring the Brigadier’s car and not really paying attention to anything else; and he’s catty, bitchy, and downright horrible to his friend. He’s rude to Tegan and Nyssa and while the Doctor is trying to smooth the rough edges. Turlough has been in the employ of the Black Guardian, who has been trying to kill the Doctor since 1978. Turlough’s partnership with the Black Guardian could be looked at as an abusive relationship between two men, with Turlough being punished for not completing his tasks. When we look at the end of Enlightenment, with Turlough turning his back on the Black Guardian, we might just view the gift of enlightenment as him realising that the Doctor is a force for good. However, if we take a wider view of the proceedings, including the two stories beforehand, then the gift of enlightenment could be seen as the removal of corruption, something which homosexuality was viewed as during the 1980s. Or perhaps Turlough accepting who he really is?

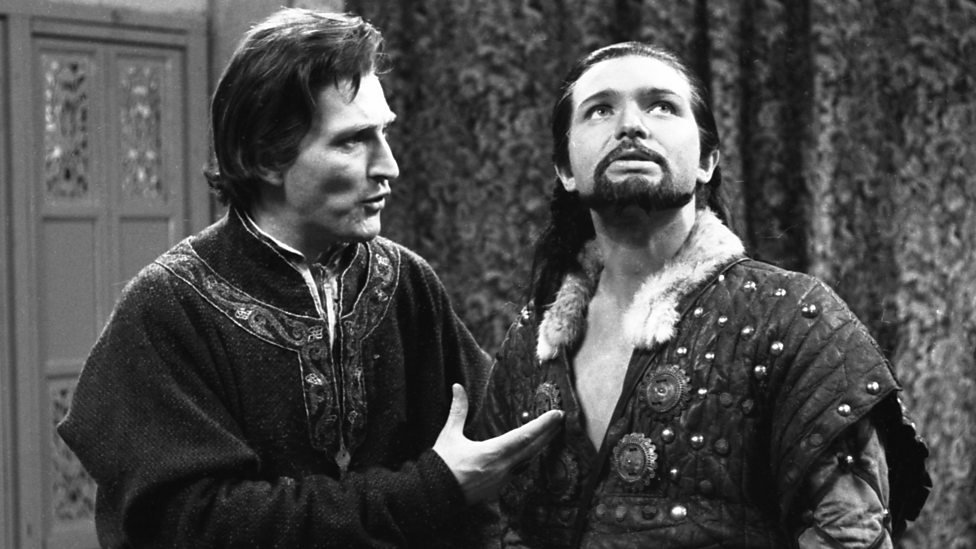

Towards the end of the 1980s, we come to The Curse of Fenric, featuring two notable characters, Doctor Judson and Commander Millington. Writer Ian Briggs later confirmed that Judson and Millington had shared a romantic relationship in the past and Judson was an allegory for Alan Turing who was chemically castrated, despite his work during World War II, for being gay and who would later kill himself. When the script was accepted, Briggs was told to get rid of the homosexual element, instead channelling Judson’s would-be-struggles with his homosexuality into his struggles with his disability. Briggs would later reintroduce the idea of a previous relationship between the two characters in his novelisation of the story in the early 1990s. But if you know where to look, there are still some subtle seeds that nod to their relationship.

Rona Munro, author of Survival, has also said that there were a number of lesbian undertones to the way she wrote the relationship between Ace and Kara. Unfortunately, the make-up and costumes of the Cheetah People meant that the work actresses Sophie Aldred and Lisa Bowerman did in rehearsals got somewhat lost at the filming stage. There is still one one slow-motion scene where they are running together which definitely has some romantic elements and one that I’ve always taken to mean that Ace fancied Kara.

The most famous of all the ’80s stories to tackle homosexual themes was 1988’s The Happiness Patrol which took a look at Margaret Thatcher’s government and tore it to shreds. There are also a lot of nods to the controversial Section 28, which saw a ban on the promotion of gay themes in schools. Outwardly camp in appearance, The Happiness Patrol sees the TARDIS painted pink and members of the Happiness Patrol wearing bright pink outfits and sparkly wigs. One scene finds members of this society walking in silence in a challenge of this society’s norms through the streets; this could be viewed as an inversion of a Pride event. Susan Q, who becomes Ace’s friend, says at one point:

“I’m tired of… smiling and pretending I’m something I’m not.”

This line is particularly evocative of a conversation that someone might have while coming out and at the start of this story, a man walks up to a sad woman and offers her a card, telling her it is an address where she can be with other killjoys. The man turns out to be an undercover member of the Happiness Patrol and is using a similar technique to real life police officers who would trick young gay men into entrapment for cottaging. And let’s not forget at the end of this story that the antagonist’s husband runs off with another man!

When the show ended with Survival in December 1989, Doctor Who would go into the Wilderness Years, a time from 1990 to 2005 when there were no new episodes of the show, excluding the 1996 TV Movie. Throughout this time, there was a fair bit of LGBTQI+ representation in Who through the expanded media. Books like Tragedy Day, Human Nature, and Damaged Goods featured gay characters; Damaged Goods was written by future showrunner Russell T Davies and saw the Doctor’s companion, Chris Cwej, going out on a date with a man in a club. Chris’ bisexuality was later explored in novels like Bad Therapy and The Room With No Doors.

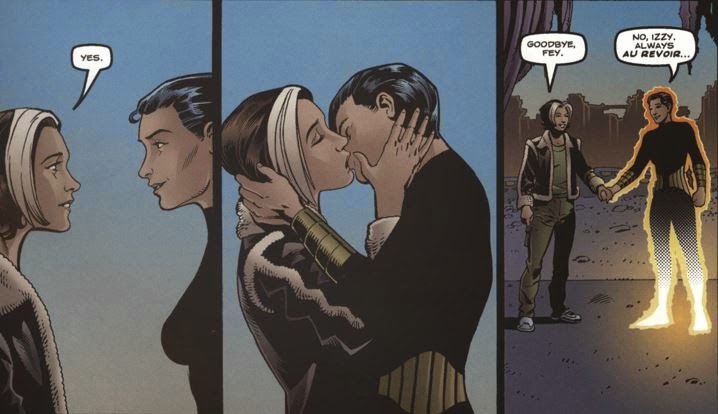

Another of the Doctor’s companions in the novels was Sam who travelled with The Eighth Doctor. She was also portrayed as bisexual. In Kate Orman’s book, Seeing I, she is seen to have feelings for a number of characters she meets throughout the novel including two men and a woman. And throughout the Eighth Doctor’s series of novels, he was seen to be in various relationships too. The Year of the Intelligent Tigers saw the Doctor in a relationship with a man called Karl Sadeghi and Orman fully intended for it be a romantic relationship. In the novel Dominion, he kisses his male companion Fitz, and later flirts with him in The Eater of Wasps. Most famously, though, for the Eighth Doctor, was a kiss shared between his comic book companion Izzy and a character called Fey. The comic called Oblivion saw Izzy finally accepting her sexuality and planting one on Fey’s lips at the end of the story.

Even the 1999 Comic Relief skit, The Curse of Fatal Death, saw the Doctor intending to marry his companion Emma; he then has to regenerate a number of times before eventually regenerating into Joanna Lumley. This is one of the show’s earliest looks at the Doctor being a woman. Even if the ending is a little heavy handed with Emma breaking off their engagement despite the Doctor still being the same person just with a different face, writer Steven Moffat would continue to include LGBT themes in his tenure as showrunner.

With the show returning to our screens in 2005, the opening story, Rose included the first use of the word “gay”, when the Doctor is flicking through an issue of Heat magazine, claiming:

“That won’t work; he’s gay and she’s an alien.”

Before his work on Doctor Who, Davies had created a Doctor Who fan, Vince Tyler, in his hit series Queer as Folk. And it’s probably not a coincidence that both Rose and Vince shared the same surname — perhaps they were cousins? In the following story, when we meet the glamourous Lady Cassandra, she says at one point that she was a boy at some point in her long, long life. Not all comments went down too well, with Rose telling the Doctor, “it was so gay” while laughing at him, having been slapped by her mother Jackie at the beginning of Aliens of London. It’s a line that hasn’t aged particularly well but was possibly a bit more acceptable when originally filmed in 2004, a time when there were few LGBTQI+ protagonists, and films and television still shied away from showing or exploring these themes.

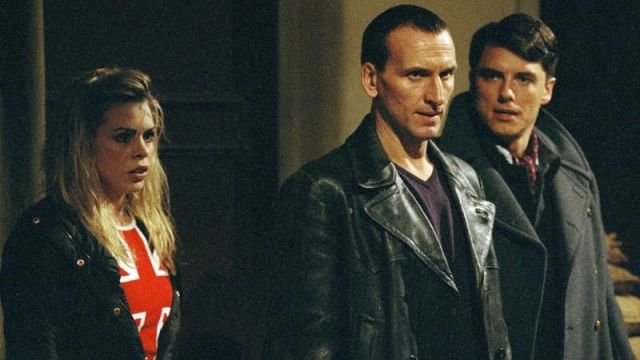

But Doctor Who‘s first openly gay companion on screen came along in 2005 too: Captain Jack Harkness. One can’t underestimate how important Jack was at the time. Not only was he the first openly gay companion — actually, pansexual is the best way to describe him — none of the stories made a fuss about it. He even gets to kiss the Doctor goodbye in The Parting of the Ways. In context, it’s because he knows he’s probably going to die giving the Doctor time to stop the Daleks, but it does mark the first same sex kiss in the main Doctor Who show. Jack’s sexuality would be explored more in the spin-off series Torchwood where he would be seen to be in a relationship with fellow member Ianto Jones.

Throughout his time as showrunner, Russell T Davies really contributed to the growing LGBTQI+ fan base to such an extent that the 2008 Pride event through London had to be paused so that everyone could watch Journey’s End, the blockbuster finale for Series 4 on a big screen in Trafalgar Square! It is little wonder that the show would begin to include many more references to various characters being part of that community — there was River Song, Jenny and Vastra, and even Clara Oswald, who was said to have smooched Jane Austin on one occasion.

It would take until 2017, though, for the Doctor to have his first on-screen companion who was explicitly only interested in women. That’s Bill Potts, played by Pearl Mackie who has since come out. It goes to show just how different things are now, compared to 1963! Bill met and fell for a woman called Heather who had a star in her eye. Heather would later become the Pilot, a creature made of sentient oil (this is Doctor Who!), and went off to explore the universe, leaving Bill behind feeling heartbroken. However, the pair would be reunited in The Doctor Falls, when Heather rescues Bill after she’s been turned into a Cyberman.

Most recently, companion Yasmin Khan fell in love with the Thirteenth Doctor and while fans seemed to really want the pair to be in a relationship, the Doctor didn’t, preferring them to just stay friends. The Thirteenth Doctor tells her in Legend of the Sea Devils that she wants things to stay the same between them; she has fallen in love with companions in the past and it’s always ended with everyone’s hearts being broken. Some viewers and fans were a little put out by the sudden interest that Yaz had in the Doctor; looking back through Jodie Whittaker’s era as the Doctor, there are seeds scattered here and there, one of the first being Yaz’s mum asking her if she and the Doctor are in a relationship.

Looking at the various spin-offs, we’ve seen Captain Jack and Ianto Jones in Torchwood but there were a number of other instances of LGBTQI+ themes. We meet one of Jack’s old boyfriends, John Hart, throughout Series 2 as well as characters sharing kisses with the same sex. But there have been times in that show when these themes weren’t handled well. One of the first times we meet Owen, he uses alien pheromones to attract men and women and sleep with them not entirely with their consent; later, in the episode Greeks Bearing Gifts, Jack gives a statement that could be read as offensive and transphobic, made even worse by the fact it comes from Captain Jack Harkness of all people.

The Sarah Jane Adventures was to see Sarah’s son Luke Smith come out as gay, had the show continued. Unfortunately, due to the untimely and sad passing of lead actress Elisabeth Sladen, Series 5 was cut short, airing just nine episodes. The short-lived Class would also feature a same sex relationship between its characters, Charlie and Mattuesz.

And now not only have we had our first canonical female Doctor, which could be viewed as the Doctor and Time Lords being gender fluid, the upcoming Fifteenth Doctor is going to be the first to be played by an openly gay man: Ncuti Gatwa.

Doctor Who has come a long way since 1963. From having little to no representation through the classic era, to allegories of Section 28 and HIV/AIDS, to a Pride event pausing for an hour in 2008… Doctor Who has always had something for everyone, no matter what sexuality you identify as, and whatever your creed, colour, or walk of life. Everyone is included: the Doctor could be anyone; the companion could be anyone. Doctor Who has become one of the most diverse shows on TV, and while LGBTQI+ topics might still be a hard topic for some people to swallow, it’s not hard to see why Doctor Who is one of the biggest inspirations to LGBTQI+ people around the world. And long may that continue!